Psychologies:

In one of your interviews, you told us that science today makes it possible to find out why I am doing something at the moment. What answers could there be?

Dmitry Leontyev:

Psychology does not give direct answers, but it can say more and more about the reasons for our behavior, because motivation is the reason for what we do: why we get out of bed in the morning, why we are doing one thing and not another at the moment.

One of the leading psychologists at the end of the last century, Heinz Heckhausen, the creator of a scientific school that is now actively working, showed that in history there were several successive views on motivation. The first, the most traditional, seems to many to be the most obvious, because it corresponds to our everyday consciousness. A person does something because he has an internal reason for it. It can be called a motive, an attraction, a need.

Previously, this could have been called instinct, but now almost no one talks about instincts in relation to humans and even in relation to animals; this concept is outdated and is used only metaphorically. So, there is an internal reason.

Our actions are explained by the interaction of internal factors and forces that are outside of us

What other options? The second view, said Heckhausen, is that we are driven to act by external forces that lie in the situation, in the circumstances. But in its pure form, the second view, even from the point of view of common sense, does not work very well.

A third view soon emerged, which still dominates today. Our actions are explained by the interaction of internal factors and forces that are outside of us: in the situation, in social, cultural requirements, and so on. These two groups of factors interact with each other, and our behavior is a product of this interaction.

Is it possible to describe what external and internal causes look like and how they interact? What serves as a stronger incentive for us to act?

D.L.:

For whom? Small children, like animals, are difficult to force to do something against their wishes. An animal can be trained based on biological needs: they won’t give you food if you break the chain, but if you sit at attention for a while, you will get food.

You can only complicate the path to satisfying initial needs. In a small child, development begins with the fact that he does only what he wants, and there is no way to go against his desires. Then, gradually, the original incentive systems are supplemented with more complex ones.

As a person integrates into a network of connections, he learns rules thanks to which he can interact with people and adapt to the social environment. He cannot be an absolutely independent subject who directly satisfies his desires; he must integrate into a rather complex system.

Ultimately, another level of motivation arises: motivation associated with the need for harmonious interaction with the social whole.

Is this motivation more likely internal or external?

D.L.:

It is rather external, because initially it is not there. It is formed in the process of life. This is what is associated with the social nature of man. Mowgli couldn't have anything like that. But it doesn't end there.

A person is not just an imprint of social matrices plus the realization of biological needs. We can go further as we develop consciousness, reflection, and attitude towards ourselves. As Viktor Frankl famously wrote in his time, the main thing in a person is the ability to take a position, develop her in relation to anything, including in relation to one’s heredity, social environment, and needs.

And where a person and his consciousness develop sufficiently, he is able to take a position: sometimes critical, sometimes controlling in relation to himself. Here the third level of needs arises, which are sometimes described as existential. The need for meaning, for a picture of the world, for the formation of one’s own identity, for an answer to the question “who am I?”, for creativity, for going beyond…

Initially, a person has many different possibilities, and their implementation depends on his life. Psychogenetic studies show that genes influence mental manifestations not directly, but indirectly. Genes interact with environmental factors, human life, and specific experiences. Their influence is mediated by our real life.

If we return to childhood, to a child: when we raise him, teach him a harmonious life in society, interaction with other people, how can we preserve in him the desire to act in accordance with what is inside him? How not to suppress it within social boundaries?

D.L.:

The point is not to act according to your inner needs. It is important that those needs, values, motivations that he assimilates from the outside, learns in the process of interaction with other people, become his own, internal needs.

Psychologist Edward Deci experimentally proved that internal motivation comes from the process itself, while external motivation is associated with what we do to obtain benefits or to avoid troubles. The process may be unpleasant and painful for us, but we know that when we complete the task, some of our needs will be satisfied thanks to this.

This external motivation is one hundred percent learned, internalized, and depends on the conditions in which the adults around us place us. At the same time, the child may be treated according to the type of training: “if you do this, you will get candy, if you don’t do it, you will stand in the corner.”

Motivation based on the principle of carrots and sticks only works in short periods of time

When a person does something through “I don’t want to,” it leads to unfavorable psychological consequences: the formation of internal alienation, insensitivity to one’s emotions, needs, and oneself. We are forced to repress our internal desires, needs and emotions because they conflict with the task we perform under the influence of external motivation.

But as Edward Deci and his co-author Richard Ryan have shown in subsequent rounds of research, extrinsic motivation is not uniform. The impulses that we internalize from the outside can remain superficial, perceived by us as something external, like something we do “for uncle.” Or they can gradually become deeper and deeper. We begin to feel them as something of our own, meaningful, important.

In its psychological consequences, such external motivation becomes very close to real, genuine, internal. It turns out to be a quality motivation, albeit external. The quality of motivation is the extent to which I feel that the reasons that make me act are mine.

High quality motivation motivates us to action, increases our life satisfaction and self-esteem

If my motives are related to my sense of self, to my own identity, then this is high quality motivation. In addition to the fact that it motivates us to action and gives us meaning, it also generates positive psychological consequences and increases our satisfaction with life and self-esteem.

And if we do something under the influence of external, superficial motivation, then we pay for it through contact with ourselves. Here's a classic version of external motivation: fame, success. Viktor Frankl very beautifully showed that the measurement of success and the measurement of meaning are perpendicular to each other.

If I strive for success, there is a risk at some point of losing my meaning. Because success is something that other people define, not myself. I find a sense of meaning in myself, and for the sake of success I can do things that seem absolutely meaningless to me, even immoral.

Experiments have shown that if a person achieves intrinsically motivated goals, it makes him happy. If a person achieves the same success, but for externally motivated purposes, then he does not become happier. Confidence brings us only the success that is associated with our internal motivation.

Is quality motivation something that good teachers and good bosses know how to cultivate or awaken?

D.L.:

Yes. But it's difficult. The paradox is that if a person is given the opportunity to choose values for himself, including giving up something, then he will assimilate them better and more firmly than if he is told: “I will teach you” and hammered it in as an obligation, a compulsion.

This is one of the paradoxes that was studied in detail in the theory of self-determination and which sounds in our latitudes as something completely unexpected and even implausible: No values can be introduced through pressure and influence. And vice versa, if a person is given the opportunity to freely relate to them and determine himself, then these values are absorbed better.

Since you mentioned self-determination: in 2008 I was pleased to hear a talk about it at a positive psychology conference. The three basic needs it identified seemed very accurate to me.

D.L.:

Self-determination theory is the most advanced theory of personality and motivation in modern scientific psychology to date. It covers different aspects, including the idea of three basic needs. The authors of the theory, Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, abandoned the idea of deriving these needs purely theoretically and for the first time determined them empirically, based on experimental data.

They propose to consider those needs, the satisfaction of which leads to an increase in subjective well-being, as basic. And failure to satisfy these needs leads to its decline. It turns out that three needs meet this criterion. This list is not closed, but convincing evidence has been obtained in relation to precisely three needs: autonomy, competence and relationships.

The need for autonomy is the need to make choices for yourself. Sometimes we manipulate a small child when we want him to eat semolina porridge. We don’t ask him: “Will you eat semolina porridge?”, we pose the question differently: “Will you have the porridge with honey or jam?” By doing so we give him a choice.

Often such a choice is false: we invite people to choose something secondary, and we take the main thing out of the equation

Often such a choice is false: we invite people to choose something relatively unimportant, and we take the main thing out of the equation. I remember there was a wonderful note in Ilya Ilf’s notebook: “You can collect stamps with teeth, or without teeth. You can collect stamped ones, or you can collect clean ones. You can cook them in boiling water, or not in boiling water, just in cold water. Everything is possible."

The second need is competence. That is, confirmation of one’s capabilities, abilities to do something, to influence events. And the third is the need for close relationships with other people, for human connections. Satisfying it also makes people happier.

Can we say, returning to where we started, that these three needs are basically what make us get out of bed in the morning and do something?

D.L.:

Unfortunately, we do not always do what makes us happy; we do not always satisfy our basic needs. We are not always intrinsically motivated. It must be said that external motivation is not necessarily a bad thing.

If I grow vegetables and fruits in my garden and eat them myself, I can do it based on internal motivation. If, within the framework of the division of labor, I specialize in something, sell the surplus on the market and buy what I need, external motivation comes into play.

If I do something for another person, it is extrinsic motivation. I can be a volunteer, work as an orderly in a hospital. There are more enjoyable activities in themselves, but what I do this for makes up for the shortcomings. Any coordination of actions, helping another person, delaying gratification and long-term planning always involve external motivation.

The interview was recorded for the Psychologies project “Status: in a relationship” on Radio “Culture” in November 2016.

Activities is called a system of various forms of realization of the subject’s relationship to the world of objects. This is how the concept of “activity” was defined by the creator of one of the variants of the activity approach in psychology, Aleksey Nikolaevich Leontyev (1903 - 1979) (10).

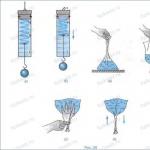

Back in the 30s. XX century in the school of A. N. Leontiev was highlighted, and in subsequent decades the structure of individual activities was carefully developed. Let's imagine it in the form of a diagram:

Activity- Motive(item of need)

Action - Purpose

Operation- Task(goal under certain conditions)

This structure of activity is open both upward and downward. From above it can be supplemented by a system of activities of various types, hierarchically organized; below - psychophysiological functions that ensure the implementation of activity.

At A. N. Leontiev’s school there are two more forms activity of the subject (by the nature of its openness to observation): external Andinternal (12).

In A.N. Leontiev’s school, a separate, specific activity was distinguished from the system of activities according to the criterion motive.

Motive is usually defined in psychology as what “drives” an activity, that for the sake of which this activity is carried out.

Motive (in the narrow sense of Leontiev)– as an object of need, i.e., to characterize the motive, it is necessary to refer to the category “need”.

A.N. Leontiev defined need in two ways:

|

Definition of NEED |

transcript |

|

1) as an “internal condition”, as one of the mandatory prerequisites for activity, which, however, is not capable of causing directed activity, but causes - as a “need” - only indicative research activity aimed at finding an object that can save the subject from the state of need . |

"virtual need" need “in oneself”, “need state”, simply “need” |

|

2) as something that directs and regulates the specific activity of the subject in the objective environment after his meeting with the object. |

"current need"(need for something specific) |

Example: Before meeting a specific object, the properties of which are generally fixed in the genetic program of the gosling, the chick has no need to follow exactly that specific object that will appear before its eyes at the moment of hatching from the egg. However, as a result of the meeting of a still “non-objectified” need (or “need state”) with a corresponding object that fits the genetically fixed scheme of an approximate “sample”, this particular object is imprinted as an object of need - and the need is “objectified”. Since then, this object becomes the motive for the activity of the subject (chick) - and he follows him everywhere.

Thus, a need at the first stage of its development is not yet a need, but a need of the organism for something that is outside of it, although reflected at the mental level.

Activity prompted by motive is realized by a person in the form actions, aimed at achieving a certain goals.

Purpose (according to Leontiev)– as a desired result of an activity, consciously planned by a person, i.e. A motive is something for which a certain activity is carried out, a goal is what is planned to be done in this regard to realize the motive.

As a rule, in human activity motive and goal do not coincide with each other.

If the goal is always conscious of the subject(he can always be aware of what he is going to do: apply to college, take entrance exams on such and such days, etc.), then the motive, as a rule, is unconscious for him (a person may not be aware of the true reason for his admission to this institute: he will claim that he is very interested, for example, in technical sciences, while in fact he is prompted to enter there by the desire to be close to his loved one).

At A.N. Leontiev’s school, special attention is paid to the analysis of a person’s emotional life. Emotions are considered here as a direct experience of the meaning of the goal (which is determined by the motive behind the goal, therefore emotions can be defined as a subjective form of the existence of motives). Emotion makes it clear to a person what the true motives for setting a particular goal may be. If, upon successful achievement of a goal, a negative emotion arises, it means that for this subject this success is imaginary, since what everything was done for was not achieved (the motive was not realized). A girl entered college, but her loved one did not.

A motive and a goal can transform into each other: a goal, when it acquires a special motivating force, can become a motive (this mechanism of turning a goal into a motive is called in the school of A.N. Leontiev “ shift of motive to goal") or, on the contrary, the motive becomes the goal.

Example: Let's assume that the young man entered college at the request of his mother. Then the true motive of his behavior is “to maintain a good relationship with his mother,” and this motive will give a corresponding meaning to the goal “to study at this particular institute.” But studying at the institute and the subjects taught there captivate this boy so much that after a while he begins to attend all classes with pleasure, not for the sake of his mother, but for the sake of obtaining the appropriate profession, since she completely captured him. There was a shift in the motive to the goal (the former goal acquired the driving force of the motive). In this case, on the contrary, the former motive can become a goal, i.e. change places with it, but something else may happen: the motive, without ceasing to be a motive, turns into a motive-goal. This last case happens when a person suddenly, clearly realizes the true motives of his behavior and says to himself: “Now I understand that I didn’t live like that: I didn’t work where I wanted, I didn’t live with who I wanted. From now on, I will live differently and now, quite consciously, I will achieve goals that are truly significant to me.”

The set goal (of which the subject is aware) does not mean that the method of achieving this goal will be the same under different conditions of its achievement and is always conscious. Different subjects often have to achieve the same goal under different conditions (in the broad sense of the word). Mode of action under certain conditions called operation and correlates Withtask (i.e., a goal given under certain conditions) (12).

Example: admission to an institute can be achieved in different ways (for example, you can pass the entrance exams “through the sieve”, you can enter based on the results of the Olympiad, you can not get the points required for the budget department and still enroll in the paid department, etc. ) (12).

|

Definition |

Note |

|

|

Activity |

a separate “unit” of a subject’s life, prompted by a specific motive, or an object of need (in the narrow sense according to Leontiev). it is a set of actions that are caused by one motive. |

The activity has a hierarchical structure. Level of special activities (or special activities) Action Level Operation level Level of psychophysiological functions |

|

Action |

basic unit of performance analysis. A process aimed at achieving a goal. |

action includes as a necessary component an act of consciousness in the form of setting and maintaining a goal. action is at the same time an act of behavior. In contrast to behaviorism, activity theory considers external movement in inextricable unity with consciousness. After all, movement without a goal is more likely a failed behavior than a true essence action = inextricable unity of consciousness and behavior through the concept of action, activity theory affirms the principle of activity the concept of action “brings” human activity into the objective and social world. |

|

Subject |

carrier of activity, consciousness and cognition |

Without a subject there is no object and vice versa. This means that activity, considered as a form of relationship (more precisely, a form of implementation of the relationship) of the subject to the object, is meaningful (necessary, significant) for the subject, it is performed in his interests, but is always aimed at the object, which ceases to be “neutral” for subject and becomes the subject of his activity. |

|

Object |

what the activity (real and cognitive) of the subject is directed towards |

|

|

Item |

denotes a certain integrity isolated from the world of objects in the process of human activity and cognition. |

activity and subject are inseparable(that’s why they constantly talk about the “objectiveness” of activity; there is no “objective” activity). It is thanks to activity that an object becomes an object, and thanks to an object, activity becomes directed. Thus, activity combines the concepts of “subject” and “object” into an inseparable whole. |

|

Motive |

the object of need, that for which this or that activity is carried out. |

Each individual activity is motivated by a motive; the subject himself may not be aware of his motives, i.e. not to be aware of them. Motives give rise to actions, that is, they lead to the formation of goals, and goals, as we know, are always realized. The motives themselves are not always realized. - Perceived motives(motives are goals characteristic of mature individuals) - Unconscious motives(manifest in consciousness in the form of emotions and personal meanings) Polymotivation of human motives. The main motive is the leading motive, the secondary motives are incentives. |

|

Target |

the image of the desired result, i.e. that result which must be achieved during the execution of the action. |

The goal is always conscious. Prompted by one or another motive to activity, the subject sets before himself certain goals, those. consciously plans his actions achieve any desired result. At the same time, achieving a goal always occurs in specific conditions, which may vary depending on the circumstances. The goal sets the action, the action ensures the realization of the goal. |

|

Task |

purpose given under certain conditions | |

|

Operation |

Ways to take action |

The nature of the operations used depends on the conditions under which the action is performed. If the action meets the goal, then the operation meets the conditions (external circumstances and opportunities) in which this goal is given. The main property of the operation is that they are little or not realized. The operation level is filled with automatic actions and skills. There are two types of operations: some arise through adaptation, direct imitation (they are practically not realized and cannot be evoked in consciousness even with special efforts); others arise from actions through their automation (they are on the verge of consciousness and can easily become actually conscious). Any complex action consists of a layer of actions and a layer of “underlying” operations. |

|

Need |

This is the original form of activity of living organisms. Objective state of a living organism. This is a state of the organism’s objective need for something that lies outside it and constitutes a necessary condition for its normal functioning. |

The need is always objective. The organic need of a biological being for what is necessary for its life and development. Needs activate the body - the search for the necessary item of need: food, water, etc. Before its first satisfaction, the need “does not know” its object; it must still be found. During the search, there is a “meeting” of the need with its object, its “recognition” or "objectification of needs." In the act of objectification, a motive is born. A motive is defined as an object of need (specification). By the very act of objectification, the need changes and transforms. - Biological need Social need (need for contact with others like oneself) Cognitive (need for external impressions) |

|

Emotions |

reflection of the relationship between the result of an activity and its motive. | |

|

Personal meaning |

the experience of increased subjective significance of an object, action, event that finds itself in the field of activity of the leading motive. |

The subject acts in the process of performing this or that activity as an organism with its own psychophysiological characteristics, and they also contribute to the specifics of the activity performed by the subject.

From the point of view of the school of A. N. Leontiev, knowledge of the properties and structure of human activity is necessary for understanding the human psyche (12).

Traditionally, the activity approach distinguishes several dynamic components(“parts”, or more precisely, functional organs) activities necessary for its full implementation. The main ones are indicative and executive components, the functions of which are, respectively, the orientation of the subject in the world and the execution of actions based on the received image of the world in accordance with the goals set by him.

The task executive The component of activity (for the sake of which activity generally exists) is not only the adaptation of the subject to the world of objects in which he lives, but also the change and transformation of this world.

However, for the full implementation of the executive function of activity, its subject needs navigate in the properties and patterns of objects, i.e., having learned them, be able to change one’s activities (for example, use certain specific operations as ways of carrying out actions under certain conditions) in accordance with the known patterns. This is precisely the task of the indicative “part” (functional organ) of the activity. As a rule, a person must, before doing anything, orient himself in the world in order to build an adequate image of this world and a corresponding action plan, i.e. orientation must run ahead of execution. This is what an adult most often does under normal operating conditions. At early stages of development (for example, in young children), orientation occurs during the performance process, and sometimes after it (12).

Resume

Consciousness cannot be considered as closed in itself: it must be brought into the activity of the subject (“opening” the circle of consciousness)

behavior cannot be considered in isolation from human consciousness. The principle of unity of consciousness and behavior.

activity is an active, purposeful process (principle of activity)

human actions are objective; they realize social – production and cultural – goals (the principle of the objectivity of human activity and the principle of its social conditionality) (10).

BULLETIN OF MOSCOW UNIVERSITY. SERIES 14. PSYCHOLOGY. 2016. No. 2 MOSCOW UNIVERSITY PSYCHOLOGY BULLETIN. 2016. # 2

THEORETICAL AND EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH

UDC 159.923, 159.9(091), 159.9(092), 331.101.3

THE CONCEPT OF MOTIVE IN A.N. LEONTIEV

AND THE PROBLEM OF MOTIVATION QUALITY

D. A. Leontyev

The article examines the formation of the concept of motive in the theory of A.N. Leontiev in correlation with the ideas of K. Lewin, as well as with the distinction between external and internal motivation and the concept of the continuum of regulation in the modern theory of self-determination by E. Deci and R. Ryan. The distinction between external motivation, based on reward and punishment, and “natural teleology” in the works of K. Levin and (external) motive and interest in the early texts of A.N. is revealed. Leontyev. The relationship between motive, goal and meaning in the structure of motivation and regulation of activity is examined in detail. The concept of the quality of motivation is introduced as a measure of the consistency of motivation with deep-seated needs and the personality as a whole, and the complementarity of the approaches of activity theory and the theory of self-determination to the problem of the quality of motivation is shown.

Key words: motive, goal, meaning, theory of activity, theory of self-determination, interest, external and internal motivation, quality of motivation.

The relevance and vitality of any scientific theory, including the psychological theory of activity, are determined by the extent to which its content allows us to obtain answers to the questions that face us today. Any theory was relevant at the time when it was created, providing answers to questions that

Leontiev Dmitry Alekseevich - Doctor of Psychological Sciences, Professor, Head. International Laboratory of Positive Psychology of Personality and Motivation, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Professor, Faculty of Psychology, Moscow State University named after M.V. Lomonosov and National Research University Higher School of Economics. Email: [email protected]

ISSN 0137-0936 (Print) / ISSN 2309-9852 (Online) http://msupsyj.ru/

© 2016 Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education “Moscow State University named after M.V. Lomonosov"

were at that time, but not all of them retained this relevance for a long time. Theories that relate to the living are able to provide answers to today's questions. Therefore, it is important to correlate any theory with the issues of today.

The subject of this article is the concept of motive. On the one hand, this is a very specific concept, on the other hand, it occupies a central place in the works not only of A.N. Leontiev, but also many of his followers who developed the activity theory. Previously, we have repeatedly turned to the analysis of the views of A.N. Leontiev on motivation (Leontiev D.A., 1992, 1993, 1999), focusing on such individual aspects as the nature of needs, multimotivation of activity and the functions of motive. Here we, briefly dwelling on the content of previous publications, will continue this analysis, paying attention primarily to the origins of the distinction between internal and external motivation found in activity theory. We will also consider the relationship between motive, purpose and meaning and correlate the views of A.N. Leontiev with modern approaches, primarily with the theory of self-determination by E. Deci and R. Ryan.

Basic provisions of the activity

motivation theories

Our previous analysis was aimed at eliminating contradictions in the traditionally cited texts of A.N. Leontyev, due to the fact that the concept of “motive” in them carried an excessively large load, including many different aspects. In the 1940s, when it was first introduced as explanatory, this stretchability could hardly be avoided; the further development of this construct led to its inevitable differentiation, the emergence of new concepts and, at the expense of them, a narrowing of the semantic field of the actual concept of “motive”.

The starting point for our understanding of the general structure of motivation is A.G.’s scheme. Asmolov (1985), who identified three groups of variables and structures that are responsible for this area. The first is the general sources and driving forces of activity; E.Yu. Patyaeva (1983) aptly called them “motivational constants.” The second group is the factors for choosing the direction of activity in a specific situation here and now. The third group is secondary processes of “situational development of motivation” (Vilyunas, 1983; Patyaeva, 1983), which make it possible to understand why people complete what they started to do, rather than switching.

each time they respond to more and more new temptations (for more details, see: Leontyev D.A., 2004). Thus, the main question in the psychology of motivation is “Why do people do what they do?” (Deci, Fiaste, 1995) breaks down into three more specific questions corresponding to these three areas: “Why do people do anything at all?”, “Why do people currently do what they do and not something else? » and “Why do people, once they start doing something, usually finish it?” The concept of motive is most often used to answer the second question.

Let's start with the main provisions of the theory of motivation by A.N. Leontiev, discussed in more detail in other publications.

1. The source of human motivation is needs. A need is an objective need of the organism for something external - an object of need. Before meeting the object, the need generates only undirected search activity (see: Leontyev D.A., 1992).

2. Meeting with an object - the objectification of a need - turns this object into a motive for purposeful activity. Needs develop through the development of their objects. It is precisely due to the fact that the objects of human needs are objects created and transformed by man that all human needs are qualitatively different from the sometimes similar needs of animals.

3. Motive is “the result, that is, the object for the sake of which the activity is carried out” (Leontyev A.N., 2000, p. 432). It acts as “... that objective in which this need (more precisely, the system of needs. - D.L.) is specified in given conditions and what activity is directed towards as motivating it” (Leontyev A.N., 1972, p. .292). A motive is a systemic quality acquired by an object, manifested in its ability to motivate and direct activity (Asmolov, 1982).

4. Human activity is multimotivated. This does not mean that one activity has several motives, but that one motive, as a rule, embodies several needs to varying degrees. Thanks to this, the meaning of the motive is complex and is determined by its connections with different needs (for more details, see: Leontyev D.A., 1993, 1999).

5. Motives perform the function of motivating and directing activity, as well as meaning formation - giving personal meaning to the activity itself and its components. In one place A.N. Leontiev (2000, p. 448) directly identifies the guiding and meaning-forming functions. On this basis he distinguishes two

categories of motives - meaning-forming motives, which carry out both motivation and meaning-formation, and “motive-stimuli”, which only motivate, but lack a meaning-forming function (Leontyev A.N., 1977, pp. 202-203).

Statement of the problem of qualitative differences

motivation of activity: K. Levin and A.N. Leontyev

The distinction between “meaning-forming motives” and “stimulus motives” is in many ways similar to the distinction, rooted in modern psychology, between two qualitatively different and based on different mechanisms types of motivation - internal motivation, conditioned by the process of activity itself, as it is, and external motivation, conditioned by benefit, which a subject can receive from the use of alienated products of this activity (money, marks, offsets and many other options). This breeding was introduced in the early 1970s. Edward Deci; The relationship between internal and external motivation began to be actively studied in the 1970-1980s. and remains relevant today (Gordeeva, 2006). Deci was able to most clearly formulate this dilution and illustrate the consequences of this distinction in many beautiful experiments (Deci, Flaste, 1995; Deci et al., 1999).

Kurt Lewin was the first to raise the question of qualitative motivational differences between natural interest and external pressures in 1931 in his monograph “The Psychological Situation of Reward and Punishment” (Lewin, 2001, pp. 165-205). He examined in detail the question of the mechanisms of the motivational effect of external pressures, forcing the child “to carry out an action or demonstrate behavior different from the one to which he is directly drawn at the moment” (Ibid., p. 165), and about the motivational effect of the opposite “situation” , in which the child’s behavior is controlled by primary or derivative interest in the matter itself” (Ibid., p. 166). The subject of Levin's direct interest is the structure of the field and the direction of the vectors of conflicting forces in these situations. In a situation of immediate interest, the resulting vector is always directed towards the goal, which Lewin calls “natural teleology” (Ibid., p. 169). The promise of reward or the threat of punishment creates conflicts in the field of varying degrees of intensity and inevitability.

A comparative analysis of reward and punishment leads Lewin to the conclusion that both methods of influence are not very effective. “Along with punishment and reward, there is also a third opportunity to evoke the desired behavior - namely, to arouse interest and arouse a tendency towards this behavior” (Ibid., p. 202). When we try to force a child or an adult to do something based on carrots and sticks, the main vector of his movement turns out to be directed to the side. The more a person strives to get closer to an undesired, but reinforced object and begin to do what is required of him, the more the forces pushing in the opposite direction grow. Levin sees a fundamental solution to the problem of education in only one thing - in changing the motivation of objects through changing the contexts in which the action is included. “The inclusion of a task in another psychological area (for example, transferring an action from the area of “school assignments” to the area of “actions aimed at achieving a practical goal”) can radically change the meaning and, therefore, the motivation of this action itself” (Ibid., p. 204).

One can see direct continuity with this work of Lewin that took shape in the 1940s. ideas of A.N. Leontiev about the meaning of actions given by the holistic activity in which this action is included (Leontiev A.N., 2009). Even earlier, in 1936-1937, based on research materials in Kharkov, an article was written, “Psychological study of children’s interests in the Palace of Pioneers and Octobrists,” published for the first time in 2009 (Ibid., pp. 46-100), where in detail not only the relationship between what we call today internal and external motivation is studied, but also their interconnection and mutual transitions. This work turned out to be the missing evolutionary link in the development of A.N.’s ideas. Leontyev about motivation; it allows us to see the origins of the concept of motive in activity theory.

The subject of the study itself is formulated as the child’s relationship to the environment and activities, in which an attitude towards the task and other people arises. There is no term “personal meaning” here yet, but in fact it is the main subject of study. The theoretical task of the study concerns the factors of formation and dynamics of children's interests, and the criteria of interest are behavioral signs of involvement or disinvolvement in a particular activity. We are talking about October students, junior schoolchildren, specifically second-graders. It is characteristic that the work sets the task of not forming certain,

given interests, but to find common means and patterns that allow stimulating the natural process of generating an active, involved attitude towards various types of activities. Phenomenological analysis shows that interest in certain activities is due to their inclusion in the structure of relationships that are significant for the child, both objective-instrumental and social. It is shown that the attitude towards things changes in the process of activity and is associated with the place of this thing in the structure of activity, i.e. with the nature of its connection with the goal.

It was there that A.N. Leontiev uses the concept of “motive” for the first time, and in a very unexpected way, contrasting motive with interest. At the same time, he states the discrepancy between the motive and the goal, showing that the child’s actions with the object are given stability and involvement by something other than interest in the very content of the actions. By motive he understands only what is now called “external motive,” as opposed to internal. This is “the driving cause of activity external to the activity itself (i.e., the goals and means included in the activity)” (Leontyev A.N., 2009, p. 83). Younger schoolchildren (second graders) engage in activities that are interesting in themselves (its purpose lies in the process itself). But sometimes they engage in activities without interest in the process itself, when they have another motive. External motives do not necessarily come down to alienated stimuli such as grades and adult demands. This also includes, for example, making a gift for mom, which in itself is not a very exciting activity (Ibid., p. 84).

Further A.N. Leontyev analyzes motives as a transitional stage to the emergence of genuine interest in the activity itself as one becomes involved in it thanks to external motives. The reason for the gradual emergence of interest in activities that previously did not arouse it is A.N. Leontyev considers the establishment of a means-end connection between this activity and what is obviously interesting to the child (Ibid., pp. 87-88). In essence, we are talking about the fact that in the later works of A.N. Leontyev was called personal meaning. At the end of the article A.N. Leontyev speaks of meaning and involvement in meaningful activity as a condition for changing the point of view on a thing and attitude towards it (Ibid., p. 96).

In this article, for the first time, the idea of meaning appears, directly associated with motive, which distinguishes this approach from other interpretations of meaning and brings it closer to Kurt Lewin’s field theory (Leontiev D.A., 1999). In the completed version we find these ideas formulated

several years later in the posthumously published works “Basic processes of mental life” and “Methodological notebooks” (Leontyev A.N., 1994), as well as in articles of the early 1940s, such as “Theory of the development of the child’s psyche”, etc. (Leontyev A.N., 2009). Here a detailed structure of activity already appears, as well as an idea of motive, covering both external and internal motivation: “The object of the activity is at the same time what motivates this activity, i.e. her motive. ...Responding to one or another need, the motive of activity is experienced by the subject in the form of desire, desire, etc. (or, conversely, in the form of the experience of disgust, etc.). These forms of experience are forms of reflection of the subject’s attitude to the motive, forms of experiencing the meaning of activity” (Leontyev A.N., 1994, pp. 48-49). And further: “(It is the discrepancy between the object and the motive that is the criterion for distinguishing an action from an activity; if the motive of a given process lies within itself, it is an activity, but if it lies outside this process itself, it is an action.) This is a conscious relationship of the subject of the action to its motive is the meaning of the action; the form of experiencing (awareness) of the meaning of an action is the consciousness of its purpose. (Therefore, an object that has meaning for me is an object that acts as an object of a possible purposeful action; an action that has meaning for me is, accordingly, an action that is possible in relation to one or another goal.) A change in the meaning of an action is always a change in its motivation” ( Ibid., p. 49).

It was from the initial distinction between motive and interest that A.N.’s later cultivation grew. Leontiev of incentive motives that only stimulate genuine interest, but are not associated with it, and meaning-forming motives that have personal meaning for the subject and in turn give meaning to the action. At the same time, the opposition between these two types of motives turned out to be overly sharpened. A special analysis of motivational functions (Leontyev D.A., 1993, 1999) led to the conclusion that the incentive and meaning-forming functions of a motive are inseparable and that motivation is provided exclusively through the mechanism of meaning-formation. “Motives-stimuli” are not without meaning and meaning-forming power, but their specificity is that they are connected with needs by artificial, alienated connections. The rupture of these connections also leads to the disappearance of motivation.

Nevertheless, one can see clear parallels between the distinction between two classes of motives in activity theory and in

theories of self-determination. It is interesting that the authors of the theory of self-determination gradually came to realize the inadequacy of the binary opposition of internal and external motivation and to introduce a model of the motivational continuum that describes the spectrum of different qualitative forms of motivation for the same behavior - from internal motivation based on organic interest, “natural teleology” , to externally controlled motivation based on “carrot and stick” and amotivation (Gordeeva, 2010; Deci, Ryan, 2008).

In the theory of activity, as in the theory of self-determination, there is a distinction between motives for activity (behavior), organically related to the nature of the activity itself, the very process of which arouses interest and other positive emotions (meaning-forming, or internal, motives), and motives that stimulate activity only due to their acquired connections with something directly significant for the subject (stimulus motives, or external motives). Any activity can be performed not for its own sake, and any motive can come into subordination to other, extraneous needs. “A student may study in order to gain the favor of his parents, but he can also fight for their favor in order to gain permission to study. Thus, we have two different relationships between ends and means, rather than two fundamentally different types of motivation” (Nuttin, 1984, p. 71). The difference lies in the nature of the connection between the subject’s activities and his real needs. When this connection is artificial, external, motives are perceived as stimuli, and activity is perceived as devoid of independent meaning, having it only thanks to the motive-stimulus. In its pure form, however, this is relatively rare. The general meaning of a specific activity is a fusion of its partial meanings, each of which reflects its relationship to any one of the needs of the subject related to this activity directly or indirectly, in a necessary way, situationally, associatively or in some other way. Therefore, activity prompted entirely by “external” motives is just as rare as activity in which they are completely absent.

It is advisable to describe these differences in terms of the quality of motivation. The quality of motivation for activity is a characteristic of the extent to which this motivation is consistent with deep needs and the personality as a whole. Intrinsic motivation is motivation that comes directly from them. External motivation is motivation that is not initially associated with them; her connection

is established with them through the construction of a certain structure of activity, in which motives and goals acquire an indirect, sometimes alienated meaning. This connection can, as the personality develops, be internalized and give rise to fairly deep formed personal values, coordinated with the needs and structure of the personality - in this case we will be dealing with autonomous motivation (in terms of the theory of self-determination), or with interest (in terms of the early works of A. N. Leontyev). Activity theory and self-determination theory differ in how they describe and explain these differences. The theory of self-determination offers a much clearer description of the qualitative continuum of forms of motivation, and the theory of activity has a better developed theoretical explanation of motivational dynamics. In particular, the key concept in the theory of A.N. Leontiev, which explains the qualitative differences in motivation, is the concept of meaning, which is absent in the theory of self-determination. In the next section we will consider in more detail the place of the concepts of meaning and semantic connections in the activity model of motivation.

Motive, purpose and meaning: semantic connections

as the basis of motivation mechanisms

The motive “launches” human activity, determining what exactly the subject needs at the moment, but he cannot give it a specific direction other than through the formation or acceptance of a goal, which determines the direction of actions leading to the realization of the motive. “A goal is a result presented in advance, towards which my action strives” (Leontyev A.N., 2000, p. 434). The motive “defines the zone of goals” (Ibid., p. 441), and within this zone a specific goal is set, obviously associated with the motive.

Motive and goal are two different qualities that the subject of purposeful activity can acquire. They are often confused because in simple cases they often coincide: in this case, the final result of an activity coincides with its subject, turning out to be both its motive and goal, but for different reasons. It is a motive because it materializes needs, and a goal because it is in it that we see the final desired result of our activity, which serves as a criterion for assessing whether we are moving correctly or not, approaching the goal or deviating from it.

A motive is what gives rise to a given activity, without which it would not exist, and it may not be recognized or may be perceived distortedly. A goal is the final result of actions anticipated in a subjective image. The goal is always present in the mind. It sets the direction of action accepted and sanctioned by the individual, regardless of how deeply it is motivated, whether it is connected with internal or external, deep or superficial motives. Moreover, a goal can be offered to the subject as a possibility, considered and rejected; This cannot happen with motive. Marx famously said: “The worst architect differs from the best bee from the very beginning in that before he builds a cell of wax, he has already built it in his head” (Marx, 1960, p. 189). Although the bee builds very perfect structures, it has no goal, no image.

And vice versa, behind any active goal there is a motive of activity, which explains why the subject accepted a given goal for fulfillment, be it a goal created by himself or given from the outside. Motive connects a given specific action with needs and personal values. The question of goal is the question of what exactly the subject wants to achieve, the question of motive is the question “why?”

The subject can act straightforwardly, doing only what he directly wants, directly realizing his desires. In this situation (and all animals are in it), the question of purpose does not arise at all. Where I do what I directly need, from which I directly receive pleasure and for the sake of which, in fact, I am doing it, the goal simply coincides with the motive. The problem of purpose, which is different from motive, arises when the subject does something that is not directly aimed at satisfying his needs, but will ultimately lead to a useful result. The goal always directs us to the future, and goal orientation, as opposed to impulsive desires, is impossible without consciousness, without the ability to imagine the future, without a time perspective. Realizing the goal, the future result, we also realize the connection of this result with what we need in the future: any goal has meaning.

Teleology, i.e. goal orientation qualitatively transforms human activity in comparison with the causally determined behavior of animals. Although causality persists and occupies a large place in human activity, it is not the only and universal causal explanation.

“A person’s life can be of two kinds: unconscious and conscious. By the first I mean a life that is governed by reasons, by the second a life that is governed by a purpose. A life governed by causes can fairly be called unconscious; this is because, although consciousness here participates in human activity, it does so only as an aid: it does not determine where this activity can be directed, and also what it should be in terms of its qualities. Causes external to man and independent of him belong to the determination of all this. Within the boundaries already established by these reasons, consciousness fulfills its service role: it indicates the methods of this or that activity, its easiest paths, what is possible and impossible to accomplish from what the reasons force a person to do. Life governed by a goal can rightly be called conscious, because consciousness is the dominant, determining principle here. It is up to him to choose where the complex chain of human actions should be directed; and also the arrangement of them all according to a plan that best suits what has been achieved.” (Rozanov, 1994, p. 21).

Purpose and motive are not identical, but they can coincide. When what the subject consciously strives to achieve (goal) is what really motivates him (motive), they coincide and overlap each other. But the motive may not coincide with the goal, with the content of the activity. For example, study is often motivated not by cognitive motives, but by completely different ones - career, conformist, self-affirmation, etc. As a rule, different motives are combined in different proportions, and it is a certain combination of them that turns out to be optimal.

A discrepancy between the goal and the motive occurs in cases when the subject does not do what he wants immediately, but he cannot get it directly, but does something auxiliary in order to ultimately get what he wants. Human activity is structured this way, whether we like it or not. The purpose of action, as a rule, is at odds with what satisfies the need. As a result of the formation of jointly distributed activities, as well as specialization and division of labor, a complex chain of semantic connections arises. K. Marx gave this a precise psychological description: “For himself, the worker does not produce the silk that he weaves, not the gold that he extracts from the mine, not the palace that he builds. For himself he produces wages. The meaning of twelve-hour work for him is not that he weaves, spins, drills, etc., but that this is a way of earning money that gives him the opportunity to eat, go to

tavern, sleep” (Marx, Engels, 1957, p. 432). Marx describes, of course, alienated meaning, but if there were no this semantic connection, i.e. connection between the goal and motivation, then the person would not work. Even an alienated semantic connection connects in a certain way what a person does with what he needs.

The above is well illustrated by a parable, often retold in philosophical and psychological literature. A wanderer walked along the road past a large construction site. He stopped a worker who was pulling a wheelbarrow full of bricks and asked him: “What are you doing?” “I’m carrying bricks,” the worker answered. He stopped the second one, who was driving the same car, and asked him: “What are you doing?” “I feed my family,” answered the second. He stopped the third and asked: “What are you doing?” “I’m building a cathedral,” answered the third. If at the level of behavior, as behaviorists would say, all three people did exactly the same thing, then they had different semantic contexts in which they inserted their actions, different meanings, motivations, and the activity itself. The meaning of work operations was determined for each of them by the breadth of the context in which they perceived their own actions. For the first there was no context, he only did what he was doing now, the meaning of his actions did not go beyond this specific situation. “I’m carrying bricks” - that’s what I do. The person does not think about the broader context of his actions. His actions are not correlated not only with the actions of other people, but also with other fragments of his own life. For the second, the context is connected with his family, for the third - with a certain cultural task, to which he was aware of his involvement.

The classic definition characterizes meaning as expressing “the relationship of the motive of activity to the immediate goal of the action” (Leontyev A.N., 1977, p. 278). Two clarifications need to be made to this definition. Firstly, meaning does not simply express this relationship, it is this relationship. Secondly, in this formulation we are not talking about any meaning, but about a specific meaning of action, or the meaning of a goal. Speaking about the meaning of an action, we ask about its motive, i.e. about why it is being done. The relation of means to ends is the meaning of the means. And the meaning of a motive, or, what is the same, the meaning of activity as a whole, is the relationship of the motive to what is larger and more stable than the motive, to a need or personal value. Meaning always connects the lesser with the greater, the particular with the general. When talking about the meaning of life, we relate life to something that is greater than individual life, to something that will not end with its completion.

Conclusion: quality of motivation in approaches

activity theories and self-determination theories

This article traces the line of development in the theory of activity of ideas about the qualitative differentiation of forms of motivation for activity, depending on the extent to which this motivation is consistent with deep needs and with the personality as a whole. The origins of this differentiation are found in some of the works of K. Levin and in the works of A.N. Leontyev 1930s. Its full version is presented in the later ideas of A.N. Leontyev about the types and functions of motives.

Another theoretical understanding of the qualitative differences in motivation is presented in the theory of self-determination by E. Deci and R. Ryan, in terms of the internalization of motivational regulation and the motivational continuum, which traces the dynamics of “growing” into motives that are initially rooted in external requirements that are irrelevant to the needs of the subject. The theory of self-determination offers a much clearer description of the qualitative continuum of forms of motivation, and the theory of activity has a better developed theoretical explanation of motivational dynamics. The key is the concept of personal meaning, connecting goals with motives and motives with needs and personal values. The quality of motivation seems to be a pressing scientific and applied problem, in relation to which productive interaction between activity theory and leading foreign approaches is possible.

REFERENCES

Asmolov A.G. Basic principles of psychological analysis in activity theory // Questions of psychology. 1982. No. 2. P. 14-27.

Asmolov A.G. Motivation // Brief psychological dictionary / Ed. A.V. Petrovsky, M.G. Yaroshevsky. M.: Politizdat, 1985. pp. 190-191.

Vilyunas V.K. Theory of activity and problems of motivation // A.N. Leontiev and modern psychology / Ed. A.V. Zaporozhets and others. M.: Publishing house Mosk. Univ., 1983. pp. 191-200.

Gordeeva T.O. Psychology of achievement motivation. M.: Meaning; Academy,

Gordeeva T.O. Self-determination theory: present and future. Part 1: Problems of theory development // Psychological research: electronic. scientific magazine 2010. No. 4 (12). URL: http://psystudy.ru

Levin K. Dynamic psychology: Selected works. M.: Smysl, 2001.

Leontyev A.N. Problems of mental development. 3rd ed. M.: Publishing house Mosk. University, 1972.

Leontyev A.N. Activity. Consciousness. Personality. 2nd ed. M.: Politizdat, 1977.

Leontyev A.N. Philosophy of psychology: from the scientific heritage / Ed. A.A. Leontyeva, D.A. Leontyev. M.: Publishing house Mosk. University, 1994.

Leontyev A.N. Lectures on general psychology / Ed. YES. Leontyeva, E.E. Sokolova. M.: Smysl, 2000.

Leontyev A.N. Psychological foundations of child development and learning. M.: Smysl, 2009.

Leontyev D.A. Human life world and the problem of needs // Psychological journal. 1992. T. 13. No. 2. P. 107-117.

Leontyev D.A. Systemic-semantic nature and functions of the motive // Bulletin of Moscow University. Ser. 14. Psychology. 1993. No. 2. P. 73-82.

Leontyev D.A. Psychology of meaning. M.: Smysl, 1999.

Leontyev D.A. General idea of human motivation // Psychology in high school. 2004. No. 1. P. 51-65.

Marx K. Capital // Marx K., Engels F. Works. 2nd ed. M.: Gospolitizdat, 1960. T. 23.

Marx K., Engels F. Hired labor and capital // Works. 2nd ed. M.: Gospolitizdat, 1957. T. 6. P. 428-459.

Patyaeva E.Yu. Situational development and levels of motivation // Bulletin of Moscow University. Ser. 14. Psychology. 1983. No. 4. P. 23-33.

Rozanov V. The purpose of human life (1892) // The meaning of life: an anthology / Ed. N.K. Gavryushina. M.: Progress-Culture, 1994. P. 19-64.

Deci E., FlasteR. Why we do what we do: Understanding Self-motivation. N.Y.: Penguin, 1995.

Deci E.L., Koestner R., Ryan R.M. The undermining effect is a reality after all: Extrinsic rewards, task interest, and self-determination // Psychological Bulletin. 1999. Vol. 125. P. 692-700.

Deci E.L., Ryan R.M. Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development and health // Canadian Psychology. 2008. Vol. 49. P. 182-185.

Nuttin J. Motivation, planning, and action: a relational theory of behavior dynamics. Leuven: Leuven University Press; Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1984.

Received 09/13/2016 Accepted for publication 10/04/2016

A. N. LEONTIEV'S CONCEPT OF MOTIVE

AND THE ISSUE OF THE QUALITY OF MOTIVATION

Dmitry A. Leontiev1 2

1 Higher School of Economics - National Research University, Moscow, Russia

2 Lomonosov Moscow State University, Faculty of Psychology, Moscow, Russia

Abstract: The paper analyzes the emergence of the concept of motive in Alexey N. Leontiev's early writings and its correspondence to Kurt Lewin's ideas and to the distinction of intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation and the concept of the continuum of regulation in the present day self-determination theory of E. Deci and R. Ryan. The distinctions of extrinsic motivation based on reward and punishment versus "natural teleology" in K. Lewin's works and of (extrinsic) motive versus interest in early A. N. Leontiev's texts are explained. The relationships between motive, goal, and personal meaning in the structure of activity regulation are analyzed. The author introduces the concept of quality of motivation referring to the degree of correspondence between motivation and one's needs and authentic Self at large; the complementarity of activity theory approach and self-determination theory as regards the quality of motivation issue is highlighted.

Key words: motive, goal, meaning, Activity theory approach, Self-determination theory, interest, extrinsic vs. intrinsic motivation, the quality of motivation.

Asmolov, A. G. (1982) Osnovnye printsipy psikhologicheskogo analiza v teorii deyatel "nosti. Voprosypsikhologii, 2, 14-27.

Asmolov, A. G. (1985) Motivatsiya. In A.V. Petrovsky, M. G. Yaroshevsky (eds.) Kratkiy psikhologicheskiy slovar (pp. 190-191). Moscow: Politizdat.

Deci, E., Flaste, R. (1995) Why we do what we do: Understanding Self-motivation. N.Y.: Penguin.

Deci, E.L., Koestner, R., Ryan, R.M. (1999) The undermining effect is a reality after all: Extrinsic rewards, task interest, and self-determination. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 692-700.

Deci, E.L., Ryan, R.M. (2008) Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development and health. Canadian Psychology, 49, 182-185.

Gordeeva, T.O. (2006) Psikhologiya motivatsii dostizheniya. Moscow: Smysl; Academy, 2006.

Gordeeva T.O. (2010) Teoriya samodeterminatsii: nastoyashchee i budushchee. Chast" 1: Problemy razvitiya teorii. Psikhologicheskie issledovaniya: elektron. nauch. zhurn. 2010. N 4 (12). URL: http://psystudy.ru

Leontiev, A.N. (1972) Problemy razvitiyapsikhiki. 3rd edition Moscow: Izd-vo MGU.

Leontiev, A.N. (1977) Deyatel "nost". Soznanie. Lichnost". 2nd izd. Moscow: Politizdat, 1977.

Leontiev, A.N. (1994) Filosofiyapsikhologii: iz nauchnogo naslediya / A.A. Leontiev, D.A. Leontiev (eds.) Moscow: Izd-vo MGU, 1994.

Leontiev, A.N. (2000) Lektsii po obshchey psikhologii / D.A. Leontiev, E.E. Sokolova (eds.). Moscow: Smysl.

Leontiev, A.N. (2009) Psikhologicheskie osnovy razvitiya rebenka i obucheniya. Moscow: Smysl.

Leontiev, D.A. (1992) Zhiznennyy mir cheloveka i problema potrebnostey. Psikhologicheskiy zhurnal, 13, 2, 107-117.

Leontiev, D.A. (1993) Sistemno-smyslovaya priroda i funktsii motiva // Vestnik Moskovskogo universiteta. Ser. 14. Psikhologiya, 2, 73-82.

Leontiev, D.A. (1999) Psikhologiya smysla. Moscow: Smysl.

Leontiev, D.A. (2004) Obshchee predstavlenie o motivatsii cheloveka. Psychologiya vuze, 1, 51-65.

Levin, K. (2001) Dinamicheskaya psikhologiya: Izbrannye trudy. Moscow: Smysl.

Marks, K. (1960) Kapital // Marks, K., Engel's, F. Sochineniya. 2nd izd. Vol. 23. Moscow: Gospolitizdat.

Marks, K., Engel's, F. (1957) Naemnyy trud i kapital // Sochineniya. 2nd izd. (Vol. 6, pp. 428-459). Moscow: Gospolitizdat.

Nuttin, J. (1984) Motivation, planning, and action: a relational theory of behavior dynamics. Leuven: Leuven University Press; Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Patyaeva, E.Yu. (1983) Situativnoe razvitie i urovni motivatsii // Vestnik Moskovskogo universiteta. Ser. 14. Psikhologiya, 4, 23-33.

Rozanov, V. (1994) Tsel "chelovecheskoy zhizni (1892). In N.K. Gavryushin (ed.) Smysl zhizni: antologiya (pp. 19-64). Moscow: Progress-Kul"tura.

Vilyunas, V.K. (1983) Teoriya deyatel "nosti i problemy motivatsii. In A.V. Zaporozhets et al. (eds.) A.N. Leontiev i sovremennayapsikhologiya (pp. 191-200). Moscow: Izd-vo MGU.

Original manuscript received September, 13, 2016 Revised manuscript accepted October, 4, 2016

Of the students and followers of L. S. Vygotsky, one of the most remarkable and influential figures in Russian psychology was Alexey Nikolaevich Leontiev(1903-1979), whose name is associated with the development of the “theory of 100

activities 1 ". In general, A. N. Leontiev developed the most important ideas of his teacher, paying, however, the main attention to what turned out to be insufficiently developed by L. S. Vygotsky - the problem of activity.

If L. S. Vygotsky saw psychology as a science about the development of higher mental functions in the process of human mastery of culture, then A. N. Leontiev oriented psychology towards the study of the generation, functioning and structure of the mental reflection of reality in the process of activity.

The general principle that guided A. N. Leontiev in his approach can be formulated as follows: internal, mental activity arises in the process of interiorization of external, practical activity and has fundamentally the same structure. This formulation outlines the direction of searching for answers to the most important theoretical questions of psychology: how the psyche arises, what is its structure and how to study it. The most important consequences of this position: by studying practical activity, we also comprehend the laws of mental activity; By managing the organization of practical activity, we manage the organization of internal, mental activity.

The internal structures formed as a result of internalization, integrating and transforming, are, in turn, the basis for the generation of external actions, statements, etc.; this process of transition from “internal to external” is designated as “exteriorization”; the principle of “interiorization-exteriorization” is one of the most important in the theory of activity.

One of these questions is: what are the criteria for mental health? On what basis can one judge whether an organism has a psyche or not? As you may have partially understood from the previous review, different answers are possible, and all will be hypothetical. Okay, idea panpsychis-

In a different vein, the problem of activity was developed by G. L. Rubinstein, the founder of another scientific school not related to L. S. Vygotsky; we will talk about it further.

ma assumes universal animation, including what we call “inanimate nature” (“pan” means “everything”), and is rarely found in psychology proper; biopsychism endows all living things with psyche; neuropsychism- only those living beings that have a nervous system; anthropopsychism gives the psyche only to man. Is it legitimate, however, to make belonging to one or another class of objects the criterion of the psyche? After all, within each class the objects are very heterogeneous, not to mention the difficulties in discussing the membership of a number of “intermediate” objects in one class or another; finally, the very attribution of the psyche to one or another class of objects is most often very speculative and is only indicated, but not proven. And is it legitimate to judge the presence of a psyche by the anatomical and physiological characteristics of the body?

A. N. Leontiev tried (like a number of other authors) to find such a criterion not in the very fact of “belonging to a category” and not in the presence of an “organ”, but in the characteristics of the organism’s behavior (showing, by the way, that the complexity of behavior does not directly correlate with complexity of the structure of the body). Based on the concept of the psyche as a special form of reflection(the philosophical basis for this approach is contained in the works of the classics of Marxism), A. N. Leontyev sees a “watershed” between the prepsychic and mental levels of reflection in the transition from irritability to sensitivity. He considers irritability as a property of the body to respond to biologically significant (biotic) influences directly related to life activity. Sensitivity is defined as the ability to respond to influences that in themselves do not carry biological significance (abiotic), but signal the organism about the associated biotic influence, which contributes to more effective adaptation. It is the presence of sensitivity in the ideas of A. N. Leontiev that is the criterion of the psychic.

In fact, to explain the response to biotic influences there is no need to resort to ideas about the psyche: these influences are directly important 102

for the survival of the organism, and reflection is carried out at the organic level. But at what level, in what form does the reflection of influences occur? on their own neutral for the body?

After all, you must admit, the smell is inedible, the sound of a predator’s growl is not dangerous!

Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that abiotic influence is reflected in the form ideal image, which means the presence of the psyche as an “internal” reality. At the level of sensitivity it becomes possible to talk about a special form of activity, directed in an ideal way. Sensitivity in its simplest form is associated with sensations, that is, the subjective reflection of individual properties of objects and phenomena of the objective world; the first stage of the evolutionary development of the psyche is designated by A. N. Leontyev as "elementary sensory psyche". Next stage - "perceptual psyche" on which perception arises as a reflection of integral objects (“perception” means “perception”); the third is named stage of intelligence, where the reflection of connections between objects occurs.

According to the idea of A. N. Leontiev, new stages of mental reflection arise as a result of the complication of activities connecting the body with the environment. Belonging to a higher evolutionary level (according to the accepted taxonomy) in itself is not decisive: organisms of a lower biological level can demonstrate more complex forms of behavior than some higher ones.

In connection with the development of A. N. Leontiev’s activity, he also discusses the problem of the emergence of consciousness. A distinctive feature of consciousness is the possibility of reflecting the world regardless of the biological meaning of this reflection, that is, the possibility of objective reflection. The emergence of consciousness is due, according to A. N. Leontyev, to the emergence of a special form of activity - collective labor.

Collective work presupposes a division of functions - participants perform various operations, which in themselves, in some cases, may seem meaningless from the point of view of directly satisfying the needs of the person performing them.

For example, during a collective hunt, the beater drives the animal away from him. But the natural act of a person who wants to get food should be exactly the opposite!

This means that there are special elements of activity that are subordinated not to direct motivation, but to a result that is expedient in the context of collective activity and plays an intermediate role in this activity. (In terms of A N. Leontieva, here the goal is separated from the motive, as a result of which the action is distinguished as a special unit of activity; we will turn to these concepts below, when considering the structure of activity.) To carry out an action, a person must understand its result in the general context, that is, comprehend it.

Thus, one of the factors in the emergence of consciousness is collective work. Another is a person’s involvement in verbal communication, which allows, through mastering the system of linguistic meanings, to become involved in social experience. Consciousness, in fact, is formed by meanings and meanings (we will also turn to the concept of “meaning” later), as well as the so-called sensory fabric of consciousness, that is, its figurative content.

So, from the point of view of A. N. Leontyev, activity acts as the starting point for the formation of the psyche at various levels. (Note that Leontiev in recent works preferred to refer the concept of “activity” to a person.)

Let us now consider its structure.

An activity represents a form of activity. Activity is stimulated by need, that is, a state of need for certain conditions of normal functioning of an individual (not necessarily biological). The need is not experienced by the subject as such; it is “presented” to him as an experience of discomfort, insecurity. satisfaction, tension and manifests itself in search activity. During the search, a need meets its object, that is, a fixation on an object that can satisfy it (this is not necessarily a material object; it could be, for example, a lecture that satisfies a cognitive need). From this moment of the “meeting”, activity becomes directed (the need for something specific, and not “in general”), demand-

ity is objectified and becomes a motive, which may or may not be realized. It is now, believes A. N. Leontyev, that it is possible to talk about activity. Activity correlates with motive, motive is what the activity is performed for; activity -■ it is a set of actions that are caused by a motive.

Action is the main structural unit of activity. It is defined as a process aimed at achieving a goal; the goal represents a conscious image of the desired result. Now remember what we noted when discussing the genesis of consciousness: the goal is separated from the motive, that is, the image of the result of the action is separated from what the activity is carried out for. The relationship of the purpose of an action to the motive represents meaning.

Action is carried out on the basis of certain methods correlated with a specific situation, that is, conditions; These methods (unconscious or little realized) are called operations and represent a lower level in the structure of activity. We defined activity as a set of actions caused by a motive; action can be considered as a set of operations subordinate to a goal.

Finally, the lowest level is the psychophysiological functions that “provide” mental processes.

This is, in general terms, a structure that is fundamentally the same for external and internal activities, which are naturally different in form (actions are performed with real objects or with images of objects).

We briefly examined the structure of activity according to A. N. Leontiev and his ideas about the role of activity in the phylogenetic development of the psyche.

Activity theory, however, also describes the patterns of individual mental development. Thus, A. N. Leontiev proposed the concept of “leading activity”, which allowed Daniil Borisovich Elkonin(1904-1984) in combination with a number of ideas of L. S. Vygotsky to construct one of the main periodizations of age development in Russian psychology. Leading activity is understood as that with which, at a given stage of development, the emergence of the most important new formations is associated and in line with which other types of activity develop; a change in leading activity means a transition to a new stage (for example, the transition from play activity to educational activity during the transition from senior preschool to junior school age).

The main mechanism in this case, according to A. N. Leontiev, is shift of motive to goal- transformation of what acted as one of the goals into an independent motive. So, for example, the assimilation of knowledge in primary school age can initially act as one of the goals in activities prompted by the motive “to obtain the teacher’s approval”, and then becomes an independent motive stimulating educational activity.

In line with the theory of activity, the problem of personality is also discussed - primarily in connection with the formation of the motivational sphere of a person. According to A. N Leontyev, a personality is “born” twice.

The first “birth” of the personality occurs in preschool age, when a hierarchy of motives is established, the first correlation of immediate impulses with social criteria, that is, the opportunity arises to act contrary to immediate impulses in accordance with social motives.

The second “birth” occurs in adolescence and is associated with awareness of the motives of one’s behavior and the possibility of self-education.