Topic 2. Genesis of corruption and bribery.

LECTURE 2

2.1. History of the emergence and development of corruption.

2.2. Characteristics of corruption relations in Russia.

2.3. The current state of corruption and bribery in Russia.

History has been familiar with the phenomenon of corruption for a very long time. Aristotle also said: “The most important thing in any political system is to arrange things through laws and other regulations in such a way that it is impossible for officials to make money.” Bribes are also mentioned in the ancient Roman 12 tables; in Ancient Rus', Metropolitan Kirill condemned “bribery” along with witchcraft and drunkenness. Under Ivan IV the Terrible, a clerk was executed for the first time for receiving more than his allotted roast goose with coins.

The Russian Code on Criminal and Correctional Punishments of 1845 (as amended in 1885, in force in Russia until October 1917) already differentiated the composition of receiving a bribe - bribery and extortion.

Also, C. Montesquieu noted: “... it is already known from the experience of centuries that every person who has power is inclined to abuse it, and he goes in this direction until he reaches the limit assigned to him.” Accordingly, manifestations of corruption are found both in states with totalitarian and democratic regimes, in economically and politically underdeveloped countries and superpowers. In principle, there are no countries that could claim exceptional chastity.

For the first time, civilized humanity encountered the phenomenon of corruption in the most ancient times; later we find its signs essentially everywhere.

For example, one of the oldest mentions of corruption is found in the cuneiform writings of ancient Babylon. As follows from deciphered texts dating back to the middle of the third millennium BC, even then the Sumerian king Urukagin faced a very acute problem of suppressing the abuses of judges and officials who extorted illegal rewards.

The rulers of ancient Egypt faced similar questions. Documents discovered during archaeological research also indicate massive manifestations of corruption in Jerusalem in the period after the Babylonian captivity of the Jews in 597 - 538. before the Nativity of Christ.

The theme of corruption is also found in biblical texts. Moreover, many authors speak bitterly about its presence and harm. For example, in one of the books of the Bible, the Book of Wisdom of Jesus son of Sirach, the father instructs his son: “Do not be a hypocrite before the lips of others and be attentive to your mouth... Let not your hand be stretched out to receive... Do no evil, and it will not befall you evil; move away from untruth and it will evade you... Do not strive to become a judge, lest you be powerless to crush untruth, lest you ever fear the face of a strong man and cast a shadow over your righteousness...” It is not difficult to notice that the very nature of the instructions indicates that the biblical society was quite familiar with the facts of bribery of judges and dishonest justice.

The ancient era did not escape the manifestations and flourishing of corruption. Its destructive influence was one of the reasons for the collapse of the Roman Empire.

Later periods of Western European history were also accompanied by the development of corrupt relations. At the same time, their presence in the life and affairs of society was reflected not only in historical documents, but also in many works of art by such masters as Chaucer (The Canterbury Tales), Shakespeare (The Merchant of Venice, An Eye for an Eye), Dante (“Hell” and “Purgatory”). So, seven centuries ago, Dante placed corrupt officials in the darkest and deepest circles of Hell. History explains his dislike of corruption by the author's political considerations, for Dante considered bribery to be the reason for the fall of the Italian republics and the success of his political opponents.

Many famous Western thinkers have paid a lot of attention to the study of manifestations of corruption. It seems that Niccolo Machiavelli explored its origins very comprehensively in this sense. It is characteristic that many of his views on this problem are very relevant today. Suffice it to recall his figurative comparison of corruption with consumption, which is difficult to recognize at first, but is easier to treat, and if it is neglected, then “although it is easy to recognize, it is difficult to cure.”

1.2. Characteristics of corruption relations in Russia.

Russia, in terms of the presence of corruption relations, has not been and is not an exception to the general rule. Their formation and development also has a long history. In particular, one of the first written mentions of promises as illegal remuneration to princely governors dates back to the end of the 14th century. The corresponding norm was enshrined in the so-called Dvina Charter Charter (the Charter Charter of Vasily I), and later clarified in the new edition of the Pskov Judgment Charter. It can be assumed that these sources only stated the existence of such acts, which clearly took place much earlier than their official normative consolidation.

The prevalence of extortion (bribery) in Russia was so significant that according to the Decree of Peter the Great of August 25, 1713 and later “legalizations,” the death penalty was determined as a punishment for extortionists. However, she did not frighten embezzlers too much. To imagine at least the approximate scale of the corruption of Russian officials, it is enough to recall such historical characters as the clerks and clerks of the royal orders of the pre-Petrine era and the clerks of the later periods, the very thieving associate of Peter the Great, Prince A.D. Menshikov, who was executed under Peter for embezzlement and extortion of the Siberian Governor Gagarin, embezzlers and bribe-takers of the highest level from the inner circle of the last Russian emperor.

Very curious in this regard is the “Note of the Highest Established Committee to Consider the Laws on Extortion and the Provisions of a Preliminary Conclusion on Measures to Eliminate This Crime,” sent to Emperor Nicholas I, dating back to August 1827. This document examines with exceptional scrupulousness the reasons for the spread of corruption in the state apparatus, provides a classification of forms of corrupt behavior, and proposes measures to counter this phenomenon.

In particular, among the main reasons are mentioned “the rarity of people who are truly just,” “a penchant for covetousness, constantly irritated by the very structure of life and not constrained by any real obstacles,” the low level of salaries of officials who “... do not teach any means for a decent maintenance ... they do not give the slightest opportunity, after satisfying the daily needs of life, to devote something to raising children, to providing first aid when they are assigned to the service, or even to a small reward for daughters when they are married off.” This contributes to the fact that the official uses the power entrusted to him by the Government “in favor of selfish interests, violates in all possible cases those laws that are entrusted to his custody, in a word, extortion is encouraged.”

The proposed list of forms of corrupt behavior, in particular bribery, is also interesting. They “are different: gifts, promises, promises, offers of services from their own patrons, seductions of all kinds; guess the inclinations of the Judges, look for their acquaintances and connections; If they don’t manage to appease one of them personally, they try to bribe him into a relative, a friend, a benefactor. Knowledge of man reveals to us that in those cases where private benefits flow, greater or lesser abuse is inseparably connected with them.”

As for measures to combat the corruption of officialdom, it was proposed to put in first place “the speedy publication of a complete systematic set of laws, which for each branch of State Administration should serve as a uniform guide in the production and resolution of cases without exception”; “the repeal of laws of those that obviously contribute to deliberate delays, oppression and forced bribes”; “the establishment in all parts of the State Administration of salaries that would be somewhat commensurate with the needs of existence in the rank in which someone is serving, and thereby would stop employees from attempting to arbitrarily satisfy these needs to the extreme, by extortion” ; “establishing fair proportionality in punishments” so that “the harm or sensitivity of punishment exceeds the benefit acquired from the crime,” and “the sensitivity of punishment for a repeated crime exceeds not only the benefit acquired through the crime, but also all the benefits that could be acquired through all repeated crimes in a person in whom vice has become a habit”; “the strictest, not just on paper, but in fact monitoring the exact execution of the Highest Decrees that protect the judiciary from the influence of the Commanders-in-Chief in different parts of the State Administration”; “the introduction of transparency in court proceedings, and in general in the administration of the clerical service, excluding only those cases that, due to their particular importance, will be excluded from this by the Supreme Government.”

However, all these good recommendations, in principle, remained unrealized, and the bureaucracy sank more and more into the abyss of corruption. It is no coincidence that the morals that reigned among the bureaucrats, including acts of corruption and their participants, were vividly reflected not only in historical documents, but also in the works of the great Russian writers N.V. Gogol, M.E. Saltykov-Shchedrin, I.I. Lazhechnikov, A.V. Sukhovo-Kobylin, A.P. Chekhov and many others.

Since ancient times, there have been three forms of corruption in Russia: honors, payment for services and promises. Offerings in the form of honor expressed respect for the one receiving it. The respectful meaning of “honor” is also manifested in the Russian custom of presenting a respected person, and especially high authorities, with bread and salt. But already in the 17th century. “honor” increasingly took on the meaning of a permitted bribe. And, of course, bribery in Russia flourished on the basis of the widespread practice of offering “honor” to officials.

Another form of donations to officials is associated with the costs of conducting and processing the affairs themselves. The income of officials in the form of payments for conducting and processing cases was taken into account when determining their salaries: if the order had a lot of cases from which they could “feed”, then they were paid less salary. That is, the practice of “feeding from

The third form of corruption is promises, i.e. payment for a favorable resolution of cases, for committing illegal acts. Most often, “promises” were expressed in overpayments for services, for conducting and processing cases, and therefore the border between the two forms of corruption was blurred and barely distinguishable.

It is enough to recall the vivid images of degenerated Soviet employees created by V. Mayakovsky, I. Ilf and E. Petrov, M. Zoshchenko and other authors. And this despite the fact that Lenin considered bribery one of the most dangerous relics and demanded the most severe, sometimes “barbaric,” as he put it, measures to combat it. In a letter to a member of the board of the People's Commissariat of Justice Kursky, he demanded: “It is necessary to immediately, with demonstrative speed, introduce a bill that penalties for bribery (extortion, bribery, summary for a bribe, etc., etc.) should be no less than ten years in prison and, in addition, , ten years of forced labor." The severity of the measures in the fight against bribery was explained by the fact that the Bolsheviks viewed it not only as a shameful and disgusting relic of the old society, but also as an attempt by the exploiting classes to undermine the foundations of the new system. One of the directives of the RCP (b) directly noted that the enormous spread of bribery, closely connected with the general lack of culture of the bulk of the population and the economic backwardness of the country, threatens to corrupt and destroy the apparatus of the workers' state.

However, despite the severity of legal measures against bribe-takers, it was not possible to eradicate this phenomenon, and its main causes were not eliminated, many of which were outlined in the above-mentioned note to the Russian Emperor Nicholas I. Even during the totalitarian rule of I. Stalin's virus of corruption was not exterminated, although, of course, it should be recognized that the model of Stalin's quasi-socialism outwardly seemed the least corrupt. However, we should not forget that totalitarianism, based on political and economic terror, also appeared outwardly in other countries as being slightly corrupt (a classic example is Hitler's Germany), which in fact was not true.

Even today, not only the elderly, but also middle-aged Russians remember the massive facts of extortion and bribery for obtaining public housing, for allocating scarce industrial and food products to trading enterprises and selling customers “through pull”, for admission to prestigious universities, for business trips abroad and things like that, which at one time were widely reported by people and even the press. And this despite the fact that nominally bribery was punished very strictly - up to the highest penalty under criminal law: the death penalty.

The conclusion about the widespread prevalence of corruption at the end of the era of socialism is allowed to come not only from the materials of trials and the press of the 1970-1980s, but also from a study of this problem conducted by one of them in 1990 in a number of regions of Russia and some union republics of the then existing USSR . Its results indicate that various types of corrupt behavior, including criminally punishable and therefore most dangerous forms, were already inherent in almost all union, republican, regional and regional state and party bodies, not to mention local ones. The most affected in this regard were the structures that provided financial and logistical support to business entities, foreign economic relations, organizing and controlling the spheres of commodity distribution and social support for the population. Moreover, if it was no longer possible to remain silent about these phenomena, they were presented as certain costs of the functioning of government bodies or individual facts that did not arise from the existing system.

All this created very favorable conditions for the further introduction of corruption into public relations during the liberalization of economic and socio-political conditions in the country at the turn of the 1990s. And, ultimately, it led to the fact that in recent years, even with continued criminal liability, bribes began to be taken, essentially, openly. The results of a study conducted already in 1999-2000 show, in particular, that with a relatively stable total number of persons convicted of bribery over the past 12-15 years, today only one in two to two and a half thousand can be brought to justice for this act persons who committed this crime (i.e., more than twenty times less than in the late 1980s and early 1990s). This essentially, if not formally, then practically decriminalized bribery as a type of crime. It is interesting that of those convicted today for bribery, up to half are representatives of law enforcement agencies, which indicates a high degree of corruption of those who, in theory, the authorities and the population should count on as the main support in countering offenders.

So, as we said above, corruption has been known since ancient times. Mention of this phenomenon is found in works on the art of government, religious and legal literature of Egypt, Mesopotamia, Judea, India and China - in all centers of ancient Eastern civilizations.

According to a number of researchers, the first mention of corruption is contained in the famous Laws of the Babylonian king Hammurabi:

Ҥ5. If a judge examined the case, made a decision and prepared a document with a seal, and then changed his decision, then this judge should be convicted of changing the decision that he made, and the amount of claim that was available in this case should be paid twelvefold; Moreover, in the assembly he should be driven from his judicial seat, and he should not return and sit with the judges in court.

The “Teaching of the King of Heracleopolis to his son Merikara” (Egypt, 22nd century BC) states: “Elevate your nobles so that they act according to your laws. He who is rich in his house is impartial; he is the lord of things and has no need.”

The Old Testament repeatedly mentions cases of corruption that took place during different periods of the existence of the Israeli state: at the dawn of its history, in the 11th century. BC, when the sons of the judge the prophet Samuel “turned aside for greed and took gifts, and judged wrongly” (1 Sam. 8:3), and much later, in the era of the divided kingdom. Prophet Amos in the 8th century. BC denounced the Israeli judges: “you oppress the judiciary, you take bribes, but you drive out the poor who seeks justice from the gates” (Amos 5:12).

The ancient Indian treatise on the art of government, “Arthashastra” (IV century BC), emphasizes that the most important task facing the king is the fight against embezzlement. The treatise lists 40 ways to steal government property and draws the disappointing conclusion that it is easier to guess the path of birds in the sky than the tricks of cunning officials. “Just as it is impossible to determine whether fish swimming in it drink water, it is impossible to determine whether officials assigned to affairs are appropriating property.” The main means of combating embezzlement is surveillance. The informer received a share of property confiscated from a person convicted of an official crime.

In ancient Roman law, there was a term “corrumpere”, which had up to fifteen meanings, including “to upset affairs”, “to waste a fortune”, “to distort the meaning”, “to falsify results”, “to distort reality”, “to bribe someone”.

In the Roman Laws of the Twelve Tables (451–450 BC) it is recorded: “Will you really consider the decree of the law severe, punishing with death the judge or mediator who was appointed during the trial [to try the case] and was convicted of that they accepted a monetary bribe in [this] case?” (Table IX. 3).

In general, the term “corruption” in Ancient Rome meant an illegal act committed by a judge or other official in the legal process. Subsequently, this concept began to be applied to various abuses by officials.

The term had a similar, and at the same time broader meaning in ancient Greece, where corruption was understood as “damaging the stomach with bad food”, “upsetting affairs”, “wasting wealth”, “bringing morals into decline”, “setting fire to property”, “ destroy freedom”, “seduce women”, “corrupt the youth”, “distort the meaning”, “falsify the results”, “distort reality”. This approach to defining corruption in ancient Greece indicates the global significance attached to this phenomenon. Perhaps corruption was equated to ethical categories, on a par with good, evil, justice, etc.

During the Middle Ages, corruption was defined in a canonical context - as seduction, the temptation of the devil. Therefore, the term “corruptibilitas” was used, meaning the frailty of man, the susceptibility of the human personality to sinful temptations.

Great thinkers of the 15th–18th centuries paid serious attention to the study of corruption. Thus, the Italian philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) compared corruption to a disease that is initially difficult to recognize but easy to treat, and later easy to recognize but almost impossible to treat.

The English materialist philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) defined corruption as “the root from which flows at all times and under all temptations contempt for all laws.” The English philosopher Francis Bacon (1561–1626) wrote about corruption: “thinking that they could buy everything with their wealth, many have first of all sold themselves.” The French thinker and historian Francois Voltaire wrote that “great sorrows always turn out to be the fruit of unbridled greed.” Thus, it was in the XV–XVIII centuries. the concept of corruption began to take on a modern meaning.

Bribery is mentioned in Russian chronicles of the 13th century. The first legislative restriction of corruption activities in Russia was implemented during the reign of Ivan III. His grandson Ivan IV the Terrible first introduced the death penalty as a punishment for excessive bribery.

Under Peter I, corruption and the tsar’s brutal fight against it became widespread in Russia. A typical episode is when, after many years of investigation, the Siberian governor M.P. was exposed for corruption and hanged. Gagarin. Literally three years later, Chief Fiscal Nesterov, the one who exposed Gagarin, was quartered for bribery.

Throughout the reign of the Romanov dynasty, corruption was a significant source of income for both minor civil servants and dignitaries. For example, the Elizabethan chancellor Bestuzhev-Ryumin received 7 thousand rubles a year for his service to the Russian Empire, and 12 thousand rubles for his services to the British crown (as an “agent of influence”).

In the Russian Empire, corruption was closely intertwined with favoritism. Numerous episodes of corrupt activities of the favorite of Peter I, Prince Alexander Menshikov, are known, for which the latter was punished by the tsar more than once.

The term “corruption” was periodically used in the works of Russian publicists of the 19th century, but the concept of “corruption” was introduced into Russian law by A.Ya. Estrin in his work “Bribery,” which was published as part of the work of the criminal law circle at St. Petersburg University only in 1913.

Of the latest pre-revolutionary episodes, in addition to G. Rasputin, it makes sense to mention the ballerina M. Kshesinskaya and Grand Duke Alexei Mikhailovich, who together, for huge bribes, helped factory owners receive military orders during the First World War.

The change in government structure and form of government in October 1917 did not eliminate corruption as a phenomenon and the need to combat it. The Decree of the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR "On Bribery" dated May 8, 1918 provided for criminal liability for bribery (imprisonment for a term of at least 5 years, combined with forced labor for the same period). Subsequently, liability for bribery was established by the Criminal Code of the RSFSR of 1922, 1926, 1960. These laws regulated liability for receiving a bribe, giving a bribe, mediation in bribery and provoking a bribe.

The history of the struggle of the Soviet government against corruption is characterized by a number of specific features. Firstly, corruption, both as a concept and as a phenomenon, was not recognized in official regulatory documents and practical activities. Instead of this definition, the terms “bribery”, “abuse of official position”, “connivance”, etc. were used.

Secondly, the reasons for the occurrence of this phenomenon were associated with the conditions inherent in bourgeois society. For example, in the closed letter of the CPSU Central Committee “On strengthening the fight against bribery and theft of people’s property” dated March 29, 1962, it was stated that bribery is “a social phenomenon generated by the conditions of an exploitative society.” The October Revolution eliminated the root causes of bribery, and “the Soviet administrative and managerial apparatus is an apparatus of a new type.” The reasons for corruption were listed as shortcomings in the work of party, trade union and government bodies, primarily in the field of education of workers.

A note from the Department of Administrative Bodies of the CPSU Central Committee and the CPC under the CPSU Central Committee on strengthening the fight against bribery in 1975–1980, dated May 21, 1981, states that in 1980 more than 6 thousand cases of bribery were identified, which is 50% more than in 1975. The emergence of organized groups is described (for example, more than 100 people in the USSR Ministry of Fisheries, headed by the deputy minister). It talks about the facts of conviction of ministers and deputy ministers in the republics, about other union ministries, about bribery and merging with criminal elements of employees of control bodies, about bribery and bribery in the prosecutor's office and courts.

The main elements of crimes are listed: release of scarce products; allocation of equipment and materials; adjustment and reduction of planned targets; appointment to responsible positions; concealment of fraud. The reasons include serious omissions in personnel work, bureaucracy and red tape when considering legitimate requests of citizens, poor handling of complaints and letters from citizens, gross violations of state, planning and financial discipline, liberalism towards bribe-takers (including in court verdicts). ), poor work with public opinion. It is reported that leading party workers (level - city and district committees) were punished for connivance with bribery. It is proposed to adopt a resolution of the Central Committee.

Thirdly, the hypocrisy of the authorities, which contributed to the acceleration of corruption, was manifested in the fact that the highest Soviet party officials were practically untouchable. Rare exceptions include the cases of Tarada and Medunov from the highest regional leadership in Krasnodar, and the case of Shchelokov. When Deputy Minister of Foreign Trade Sushkov was convicted of bribes and abuses, the KGB and the Union Prosecutor General's Office reported to the Central Committee about the side results of the investigation: Minister Patolichev systematically received expensive items made of gold and precious metals, rare gold coins as gifts from representatives of foreign companies. The matter was hushed up.

Fourthly, only representatives of this apparatus fought against corruption among the state apparatus. This led to two consequences: those who fought were organically unable to change the root causes that gave rise to corruption, since they went back to the most important conditions for the existence of the system; the fight against corrupt officials often developed into a fight against competitors in the markets for corrupt services.

Thus, corruption undoubtedly existed in the USSR, but it was distinguished by a number of features. Historian F.I. Razzakov in his book “Corruption in the Politburo: the case of the “Red Uzbek”” writes that “... in the USSR there was the first (administrative type of corruption) - that is, the provision of illegal or legal, but only for a select few, benefits and benefits for the purpose of obtaining benefits and without changes to existing laws and regulations.”

The entire post-war period, during and after Perestroika, the growth of corruption occurred against the backdrop of a weakening of the state machine. It was accompanied by the following processes: a decrease in centralized control, then the collapse of ideological bonds, economic stagnation, and then a drop in the level of economic development, and, finally, the collapse of the USSR and the emergence of a new country - Russia, which at first could only nominally be considered a state. Gradually, the centrally organized corruption of the state was replaced by a “federal” structure of many corrupt systems.

Thus, the current state of corruption in Russia is largely due to long-established trends and a transitional stage, which in other countries in a similar situation was accompanied by an increase in corruption. Among the most important factors determining the growth of corruption and having historical roots, in addition to the dysfunctions of the state machine and some historical and cultural traditions, it should be noted:

· rapid transition to an economic system not supported by the necessary legal framework and legal culture;

· the absence in Soviet times of a normal legal system and corresponding cultural traditions;

· collapse of the party control system.

Corruption is an international problem. It is characteristic of all countries, regardless of the political system and level of political development and differs only in scale.

In 1994, Switzerland, which prided itself on the integrity of its civil servants, was shocked by a huge scandal involving an official from the canton of Zurich, an auditor of restaurants and bars. He was accused of bribes amounting to almost $2 million. Immediately after this, an investigation was launched against 5 bribe-taking auditors from the Swiss government, who patronized individual companies in organizing government supplies. Then two more scandals broke out.

Numerous cases of corruption in Italy, affecting the highest levels of politics, led to more than 700 businessmen and politicians being brought to trial as a result of investigations that began in 1992 in Milan.

In September 1996, a special conference on combating corruption was held in Berlin. According to the materials presented there, in many large cities of Germany, prosecutors are busy investigating thousands of cases of corruption: in Frankfurt am Main - more than 1000, in Munich - about 600, in Hamburg - about 400, in Berlin - about 200. In 1995 it was official Almost three thousand cases of bribery have been registered. In 1994, almost 1,500 people were put on trial, and in 1995, more than 2,000 people, and experts consider these data to be just the tip of the iceberg. Departments for checking foreign refugees, registration points for new cars and many other institutions are involved in corruption. Thus, for cash you can illegally “buy” the right to open a restaurant or casino, driver’s licenses, and licenses to tow illegally parked cars. The construction industry is most affected by corruption.

In one of its newsletters, the international public organization Transparency International (hereinafter referred to as TI), whose goal is to resist corruption at the international and national levels and in business, stated: “It (corruption) has become a leading phenomenon in many leading industrial countries, wealth and sustainable whose political traditions, however, make it possible to hide the scope of the enormous damage caused by corruption to the social and humanitarian spheres.” A study conducted by TI's national affiliates in 1995 found that "public sector corruption takes the same forms and affects the same areas whether it occurs in a developed or developing country."

The problem of the need to fight corruption in Russia became obvious already in the early 1990s. By this time, several projects aimed at combating corruption had been prepared and submitted to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. The President of the Russian Federation issued Decree “On the fight against corruption in the public service system” No. 361 dated April 4, 1992. This Decree noted the consequences generated by this negative phenomenon and defined a number of measures aimed at combating corruption. The decree was a step in the right direction, but it decided little and was poorly implemented. The concept of corruption was not given in this Decree.

On June 20, 1993, the Supreme Council of the Russian Federation adopted the Law of the Russian Federation “On the Fight against Corruption.” However, this Law was not signed by the President of the Russian Federation and did not come into force. After the dissolution of the Supreme Council of the Russian Federation, the lower house of the new parliament - the State Duma - continued to work on improving the draft Law. The new version of the Federal Law “On the Fight against Corruption” was adopted twice by the State Duma of the Russian Federation and was approved by the Federation Council in December 1995. However, at the end of December of the same year, it was rejected by the President of the Russian Federation.

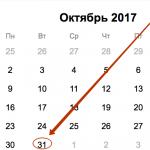

In November 1997, the State Duma adopted the Federal Law “On the Fight against Corruption” in the third reading. However, due to a number of legal and technical shortcomings, this normative act did not pass the remaining stages of lawmaking. And only on December 25, 2008, Federal Law No. 273-FZ “On Combating Corruption” was adopted.

Most often, corruption refers to the receipt of bribes and illegal monetary gains by government bureaucrats who extort them from citizens for the sake of personal enrichment. However, in a more general sense, participants in corruption relations can be not only government officials, but also, for example, company managers; bribes can be given not in money, but in another form; The initiators of corruption relations are often not government officials, but entrepreneurs. Since the forms of abuse of official position are very diverse, different types of corruption are distinguished according to different criteria (Table 1).

| Table 1. TYPOLOGY OF CORRUPTION RELATIONS | |

| Criteria for the typology of corruption | Types of corruption |

| Who abuses their official position | State (corruption of government officials) Commercial (corruption of company managers) Political (corruption of political figures) |

| Who initiates corruption relations? | Requesting (extorting) bribes on the initiative of a managerial person. Bribery initiated by the petitioner |

| Who is the briber? | Individual bribe (from a citizen)Entrepreneurial bribe (from a legal company) Criminal bribery (from criminal entrepreneurs - for example, drug mafia) |

| Form of benefit received by the bribe-taker from corruption | Cash bribes Exchange of services (patronage, nepotism) |

| Goals of corruption from the point of view of the bribe giver | Accelerating bribe (so that the person receiving the bribe will quickly do what he must do according to his duty) Inhibitory bribe (so that the person receiving the bribe violates his official duties) Bribe “for good attitude” (so that the person receiving the bribe does not make far-fetched faults with the bribe-giver) |

| Degree of centralization of corruption relations | Decentralized corruption (each bribe-giver acts on his own initiative) Centralized “bottom-up” corruption (bribes regularly collected by lower-ranking officials are divided between them and more senior ones) Centralized top-down corruption (bribes regularly collected by senior officials are partially passed on to their subordinates) |

| Level of prevalence of corruption relations | Grassroots corruption (in the lower and middle echelons of power) Top corruption (among senior officials and politicians) International corruption (in the sphere of world economic relations) |

| Degree of regularity of corruption ties | Episodic corruption Systematic (institutional) corruption Kleptocracy (corruption as an integral component of power relations) |

Corruption is the flip side of the activities of any centralized state that claims broad accounting and control.

In primitive and early class societies, payment to a priest, chief or military commander for personally seeking their help was considered a universal norm. The situation began to change as the state apparatus became more complex and professionalized. High-ranking rulers demanded that lower-ranking “employees” be content only with a fixed “salary.” On the contrary, lower-ranking officials preferred to secretly receive from petitioners (or demand from them) additional payment for the performance of their official duties.

In the early stages of the history of ancient societies (ancient Greek city-states, republican Rome), when there were no professional government officials, corruption was almost absent. This phenomenon began to flourish only in the era of the decline of antiquity, when such government officials appeared about whom they said: “He came poor to a rich province, and left rich from a poor province.” At this time, a special term “corrumpire” appeared in Roman law, which was synonymous with the words “spoil”, “bribe” and served to designate any abuse of office.

Where the power of the central government was weak (for example, in Europe in the early Middle Ages), the use of official positions for personal extortion from the population often became the generally accepted norm. Thus, in medieval Russia, “feeding” governors and appropriating fees for resolving conflicts was considered the usual income of service people, along with salaries from the treasury or receiving estates.

The more centralized the state was, the more strictly it limited the independence of citizens, provoking low- and high-level officials to secretly violate the law in favor of subjects who wanted to get rid of strict supervision. Exemplary punishments of corrupt officials usually yielded almost no results, because new bribe extorters appeared in place of those eliminated (demoted or executed). Since the central government usually did not have the strength to completely control the activities of officials, it was usually content with maintaining a certain “tolerant norm” of corruption, suppressing only its too dangerous manifestations.

This moderate tolerance for corruption is most clearly visible in societies Asian production method. In the countries of the pre-colonial East, on the one hand, rulers claimed universal “accounting and control”, but, on the other hand, they constantly complained about the greed of officials who confused their own pockets with the state treasury. It is in Eastern societies that the first studies of corruption appear. Yes, author Arthashastras identified 40 means of theft of state property by greedy officials and sadly stated that “just as one cannot help but perceive honey if it is on the tongue, so the king’s property cannot be misappropriated, even if only a little, by those in charge of this property.”

A radical change in society's attitude towards the personal income of government officials occurred only in Western Europe of the modern era. The ideology of the social contract proclaimed that subjects pay taxes to the state in exchange for the fact that it wisely develops laws and strictly monitors their strict implementation. Personal relationships began to give way to purely official ones, and therefore the receipt of personal income by an official, in addition to his salary, began to be interpreted as a flagrant violation of public morality and the law. In addition, the ideology of economic freedom, justified by representatives of neoclassical economic theory, demanded that the state “let people do their own things and let things take their own course.” If officials' capacity for regulatory intervention decreased, so did their ability to extort bribes. Ultimately, in the centralized states of modern times, official corruption, although it did not disappear, was sharply reduced.

A new stage in the evolution of corruption in developed countries was the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. On the one hand, a new rise in government regulation measures and, accordingly, the power of officials began. On the other hand, big business was born, which in the competitive struggle began to resort to “buying up the state” - no longer to the occasional bribery of individual small government officials, but to the direct subordination of the activities of politicians and senior officials to the protection of the interests of capital. As the importance of political parties grew in developed countries (especially in Western Europe after World War II), party corruption developed, when large firms paid not to politicians personally, but to the party treasury for lobbying their interests. Major politicians have increasingly begun to view their position as a source of personal income. Thus, in Japan and today, politicians who help private corporations obtain lucrative contracts expect to receive a percentage of the deal. At the same time, the independence of internal company employees began to grow, who also have the opportunity to abuse their position.

In the second half of the 20th century, after the emergence of a large number of politically independent “third world” countries, their state apparatus, as a rule, initially turned out to be highly susceptible to systemic corruption. The fact is that the “eastern” traditions of personal relations between the boss and the petitioners are superimposed on huge uncontrolled opportunities associated with state regulation of many spheres of life. For example, Indonesian President Suharto was known as "Mr. 10 Percent" because all foreign corporations operating in that country were asked to pay a clearly defined bribe to the president and members of his family clan. “Bottom-up” corruption was typical, when the boss could blame all the blame on his subordinates, but there was also “top-down” corruption, when corrupt senior officials were not at all embarrassed to openly take bribes and even share them with subordinates (such a system of corruption existed, for example , in South Korea). In the “third world,” kleptocratic regimes appeared (in the Philippines, Paraguay, Haiti, and most African countries), where corruption completely permeated all types of socio-economic relations, and simply nothing was done without a bribe.

The growth of world economic relations also stimulated the development of corruption. When concluding contracts with foreign buyers, large transnational corporations they even began to legally include expenses for “gifts” in the costs of negotiations. In the 1970s, a scandal with the American company Lockheed thundered throughout the world, which, in order to sell its not very good aircraft, gave large bribes to high-ranking politicians and officials of Germany, Japan and other countries. Around this time, corruption began to be recognized as one of the global problems of our time, hindering the development of all countries of the world.

The problem became even more pressing in the 1990s, when post-socialist countries demonstrated the extent of corruption comparable to the situation in developing countries. A paradoxical situation often arose when the same person simultaneously occupied important positions in both the public and commercial sectors of the economy; as a result, many officials abused their positions, not even accepting bribes, but directly protecting their personal commercial interests.

Thus, the general trends in the evolution of corruption relations in the 20th century. – this is a gradual multiplication of their forms, a transition from episodic and grassroots corruption to systematic apex and international corruption.

Causes of corruption.

The theoretical foundations of the economics of corruption were laid in the 1970s in the works of American neo-institutional economists. Their main idea was that corruption appears and grows if there is rent associated with government regulation of various spheres of economic life (the introduction of export-import restrictions, the provision of subsidies and tax benefits to enterprises or industries, the presence of price controls, multiple exchange rate policies etc.). At the same time, those officials who receive low salaries are more focused on corruption. More recently, empirical studies have confirmed that corruption is reduced if a country has few foreign trade restrictions, if industrial policy is based on the principles of equal opportunity for all enterprises and industries, and if government officials are paid higher than private sector workers of the same qualifications.

In modern economic science, it is customary to note the multiplicity of causes of corruption, highlighting economic, institutional and socio-cultural factors.

Economic The causes of corruption are, first of all, low salaries of civil servants, as well as their high powers to influence the activities of firms and citizens. Corruption flourishes wherever officials have broad powers to dispose of any scarce goods. This is especially noticeable in developing and transition countries, but is also evident in developed countries. For example, in the United States, many manifestations of corruption have been observed during the implementation of a program of preferential housing for needy families.

Institutional The reasons for corruption are considered to be a high level of secrecy in the work of government departments, a cumbersome reporting system, a lack of transparency in the lawmaking system, and weak state personnel policies that allow the spread of sinecures and opportunities for promotion regardless of the actual performance of employees.

Socio-cultural The causes of corruption are demoralization of society, lack of awareness and organization of citizens, public passivity in relation to the willfulness of “those in power.”

In those countries where all three groups of factors operate (these are, first of all, developing and post-socialist countries), corruption is the highest. On the contrary, in the countries of Western European civilization these factors are much less pronounced, and therefore corruption there is more moderate.

To explain the causes and essence of corruption relations, economists usually use the model “guarantor (principal) – executor (agent) – ward (client)” (see Fig. 1).

In this model, the central government acts as a principal (P): it sets rules and assigns specific tasks to agents (A), middle- and lower-level officials. Officials act as intermediaries between the central government and clients (K), individual citizens or firms. In exchange for paying taxes, the agent, on behalf of the principal, provides various services to clients (licenses the activities of firms, issues social benefits to citizens, hires workers for the public service, etc.). For example, within the tax service, the principal is the state represented by the head of the tax service, the agents are tax collectors, and all taxpayers are clients. In exchange for paying taxes, taxpayers are given the opportunity to operate legally, otherwise they face fines and other penalties.

The quality of a regulatory system depends on whether conflicts of interest arise in this system between the principal and the agent. The government, in principle, has neither the time nor the ability to personally serve each client, so it delegates the authority to serve them to officials, prescribing certain rules for them. Agent-officials, knowing their clients better than the government-principal, can work more effectively with clients. But it is difficult for the principal to control how numerous intermediary agents perform the prescribed work, especially since officials may deliberately hide information about the true results of their activities. Since the honesty of the official-agent cannot be completely controlled, the agent himself decides whether to be “honest”. The official's decision depends on the expected rewards for good work and the expected penalties for abuse. For example, in the Russian tax system, the payment of a tax official almost does not depend on the amount of funds contributed to the budget due to hidden taxes identified by him. This leads to the fact that the tax collector is often more interested in receiving bribes than in honest service.

Illegal remuneration to an official agent from his clients can be given for various reasons. A citizen or a company can give a bribe so that an official will provide them with the required services more quickly, “out of turn” (accelerating bribe). More often, however, officials are bribed so that they provide their clients with more services offered by the state, and collect less taxes than required by law (inhibitory bribe). It also happens that an official has ample opportunity to find fault on flimsy pretexts; then bribes are given so that the official does not take advantage of his opportunities to show tyranny (a bribe “for a good attitude”).

To prevent corruption, they try to assign very high salaries to the most responsible employees and at the same time tighten penalties for violating their official duty. However, many researchers note that in many cases, government salaries cannot compete with the financial capabilities of potential bribe givers (if they are large legal businessmen or mafia bosses). A decent agent salary is a necessary but not sufficient condition for preventing corruption. Therefore, the state-principal supplements (or even replaces) high incentives with “appeals to honest behavior.” This means that the government is trying to create psychological barriers against the self-interest of agents, for example, raising the moral level of citizens through the mechanism of training and ideological propaganda. In addition, the government-principal encourages direct communications with clients (receiving complaints from the public), which serve as an additional and very important tool for controlling the actions of government agents.

Thus, the “agent-client” relationship depends on the agent’s salary and the breadth of their powers, and the “principal-agent” relationship depends on the degree of control of the principal over the agents and the influence of clients on the principal. Moral norms influence all types of relationships in this system, determining the extent to which deviations from the requirements of the law are permissible.

Some foreign economists express an extremely laconic definition of the main causes of corruption with the following formula:

corruption = monopoly + arbitrariness – responsibility.

This means that the possibility of corruption directly depends on the state’s monopoly on certain types of activities (for example, purchasing weapons) and on the lack of control over the activities of officials, but inversely depends on the likelihood and severity of punishment for abuse.

Measuring corruption.

The scale of corruption is quite difficult to assess. This is due, first of all, to the fact that it (like other types of shadow economic activity) is, in principle, hidden from official statistical accounting. Since government officials have more opportunities to hide their wrongdoings than ordinary citizens, corruption is reflected in crime statistics less clearly than many other types of crimes. In addition, many types of corruption are not even directly related to the payment of monetary rewards, and therefore cannot be assessed.

To obtain comparative data on the degree of development of corruption in different countries, sociological surveys and expert assessments are most often used.

Currently the most respected corruption perception index(Corruption Perceptions Index - CPI), which is calculated by the international organization Transparency International (literally translated - “International Transparency”). This non-profit, non-governmental organization for the study of corruption and the fight against it integrates data from scientific research conducted on different countries by individual economists and organizations for the 3 years preceding the calculation of the composite index. These studies compare the subjective assessments given by businessmen and analysts of the degree of corruption in different countries. In the process of summarizing data from individual studies, each country receives a score on a 10-point scale, where 10 points means the absence of corruption (the highest “transparency” of the economy), and 0 points means the highest degree of corruption (minimal “transparency”).

Corruption perception indices began to be calculated in 1995. The database used by Transparency International is constantly growing: if in 1995 the CPI was calculated for 41 countries of the world, then in 2003 - already for 133. The 2003 Corruption Perceptions Index summarized the results of 17 public opinion studies conducted by 13 independent organizations , and the final list included only those countries that were covered by at least three studies.

Research by Transparency International shows a strong differentiation of countries around the world in terms of the degree of development of corruption (Table 2).

|

COUNTRIES |

Corruption Perception Index | ||

| 1995 | 1999 | 2003 | |

|

Highly developed countries |

|||

| Finland | 9,1 | 9,8 | 9,7 |

| Denmark | 9,3 | 10,0 | 9,5 |

| Sweden | 8,9 | 9,4 | 9,3 |

| Canada | 8,9 | 9,2 | 8,7 |

| United Kingdom | 8,6 | 8,6 | 8,7 |

| Germany | 8,1 | 8,0 | 7,7 |

| Ireland | 8,6 | 7,7 | 7,5 |

| USA | 7,8 | 7,5 | 7,5 |

| Japan | 6,7 | 6,0 | 7,0 |

| France | 7,0 | 6,6 | 6,9 |

| Spain | 4,4 | 6,6 | 6,9 |

| Italy | 3,0 | 4,7 | 5,3 |

|

Developing countries |

|||

| Singapore | 9,3 | 9,1 | 9,4 |

| Hong Kong | 7,1 | 7,7 | 8,0 |

| Chile | 7,9 | 6,9 | 7,4 |

| Botswana | 6,1 | 5,7 | |

| Taiwan | 5,1 | 5,6 | 5,7 |

| South Korea | 5,6 | 3,8 | 4,3 |

| Brazil | 2,7 | 4,1 | 3,9 |

| Mexico | 3,2 | 3,4 | 3,6 |

| Egypt | 3,3 | 3,3 | |

| India | 2,8 | 2,9 | 2,8 |

| Argentina | 5,2 | 3,0 | 2,5 |

| Indonesia | 1,9 | 1,7 | 1,9 |

| Kenya | 2,0 | 1,9 | |

| Nigeria | 1,6 | 1,4 | |

|

Countries with economies in transition |

|||

| Slovenia | 6,0 | 5,9 | |

| Estonia | 5,7 | 5,5 | |

| Hungary | 4,1 | 5,2 | 4,8 |

| Cuba | 4,6 | ||

| Belarus | 3,4 | 4,2 | |

| Czech Republic | 4,6 | 3,9 | |

| Poland | 4,2 | 3,6 | |

| China | 2,2 | 3,4 | 3,4 |

| Armenia | 2,5 | 3,0 | |

| Russia | 2,4 | 2,7 | |

| Uzbekistan | 1,8 | 2,4 | |

| Ukraine | 2,6 | 2,3 | |

| Azerbaijan | 1,7 | 1,8 | |

| Georgia | 2,3 | 1,8 | |

It is quite natural that poverty and corruption go “hand in hand”: the most highly corrupt countries are, first of all, developing countries with low living standards. Post-socialist countries have slightly better scores, but corruption is also quite high here. However, wealth in itself does not guarantee freedom from corruption. Germany and the US have about the same score as much poorer Ireland; France turned out to be worse than Chile, Italy - worse than Botswana.

Differentiation within groups of countries with approximately the same standard of living strongly depends on the national economic culture and government policies. Thus, for countries with Confucian culture (China, Japan, Singapore, Taiwan), where since ancient times an honest and wise official was considered a cult figure, corruption indices are noticeably lower than, for example, in the countries of South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh), in which there is no tradition of respect for managerial work.

In general, therefore, two universal patterns can be noted:

corruption is usually higher in poor countries but lower in rich ones;

Corruption is generally lower in countries of Western European civilization and higher in peripheral countries.

A comparison of corruption perception indices over different years shows that many countries are significantly changing the degree of corruption in a relatively short period of time. For example, in countries such as Italy and Spain the situation has noticeably worsened, while in Argentina and Ireland it has improved. However, cross-temporal comparisons of CPI indices must be made very carefully, since changes in a country's scores may be the result not only of changed perceptions of corruption, but also of changed samples and survey methodology.

| Table 3. BRIBE INDICES FOR SOME COUNTRIES OF THE WORLD | |||

| Countries | Bribe Payers Index | ||

| 2002 | 1999 | ||

| 1 | Australia | 8,5 | 8,1 |

| 2 | Sweden | 8,4 | 8,3 |

| 3 | Switzerland | 8,4 | 7,7 |

| 4 | Austria | 8,2 | 7,8 |

| 5 | Canada | 8,1 | 8,1 |

| 6 | Netherlands | 7,8 | 7,4 |

| 7 | Belgium | 7,8 | 6,8 |

| 8 | United Kingdom | 6,9 | 7,2 |

| 9 | Singapore | 6,3 | 5,7 |

| 10 | Germany | 6,3 | 6,2 |

| 11 | Spain | 5,8 | 5,3 |

| 12 | France | 5,5 | 5,2 |

| 13 | USA | 5,3 | 6,2 |

| 14 | Japan | 5,3 | 5,1 |

| 15 | Malaysia | 4,3 | 3,9 |

| 16 | Hong Kong | 4,3 | |

| 17 | Italy | 4,1 | 3,7 |

| 18 | South Korea | 3,9 | 3,4 |

| 19 | Taiwan | 3,8 | 3,5 |

| 20 | China | 3,5 | 3,1 |

| 21 | Russia | 3,2 | The index was not calculated for this country |

If the CPI index shows the propensity of officials of different countries take bribes, then to assess the propensity of entrepreneurs in different countries give bribes Transparency International uses a different index – bribery index(Bribe Payers Index - BPI). Similar to the CPI index, the propensity of companies in exporting countries to pay bribes was assessed on a 10-point scale, where the lower the score, the higher the willingness to bribe. The collected data show (Table 3) that many peripheral countries famous for their corruption (for example, Russia, China) are willing to not only take, but also give bribes abroad. As for firms from developed countries, their propensity to resort to bribery turned out to be quite moderate. It is characteristic that Sweden was among the “cleanest” in both the CPI and BPI index.

In addition to the CPI and BPI indices, other indicators are also used to comparatively assess the development of corruption in different countries - for example, barometer of global corruption(Global Corruption Barometer), economic freedom index(Index of Economic Freedom), opacity index(Opacity Index), etc.

The influence of corruption on social development.

Corruption has a strong and usually negative impact on the economic and social development of any country.

Economic harm anti-corruption is associated, first of all, with the fact that corruption is an obstacle to the implementation of the state’s macroeconomic policy. As a result of corruption at the lower and middle levels of the management system, the central government ceases to receive reliable information about the real state of affairs in the country's economy and cannot achieve its intended goals.

Corruption seriously distorts the very motives behind government decisions. Corrupt politicians and bureaucrats are more likely to direct public resources to areas of activity where strict control is impossible and where the possibility of extorting bribes is higher. They are more likely to finance the production of, for example, combat aircraft and other large investment projects than to publish school textbooks and increase teachers' salaries. There is a well-known anecdotal example when in 1975 in Nigeria, a generously bribed government placed orders abroad for such a gigantic amount of cement that exceeded the capabilities of its production in all countries of Western Europe and the USSR combined. Comparative cross-country studies confirm that corruption greatly distorts the structure of public spending: corrupt governments allocate much less money to education and health care than non-corrupt ones.

The main negative manifestation of the economic impact of corruption is the increase in costs for entrepreneurs (especially for small firms that are more defenseless against extortionists). Thus, the difficulties of business development in post-socialist countries are largely due to the fact that officials often force entrepreneurs to give bribes, which turn into a kind of additional taxation (Table 4). Even if an entrepreneur is honest and does not give bribes, he suffers from corruption, since he is forced to spend a lot of time communicating with deliberately picky government officials.

Finally, corruption and bureaucratic red tape when processing business documents slow down investment (especially foreign ones) and ultimately economic growth. For example, a model developed in the 1990s by the American economist Paolo Mauro allowed him to conjecture that an increase in the calculated “bureaucratic efficiency” (an index close to the Corruption Perceptions Index calculated by Transparency International) by 2.4 points reduces the country’s economic growth rate by about 0 .5%. According to calculations by another American economist, Shan-Chin Wai, an increase in the corruption index by one point (on a ten-point scale) is accompanied by a 0.9% drop in foreign direct investment. However, when reviewing corruption indices, it was already mentioned that there is still no clear negative correlation between the level of corruption and the level of economic development; this connection is noticeable only as a general pattern, from which there are many exceptions.

As for the social negative consequences of corruption, it is generally accepted that it leads to injustice - to unfair competition between firms and to unjustified redistribution of citizens' income. The fact is that it is not the most efficient legal company, or even a criminal organization, that can give a larger bribe. As a result, the incomes of bribe givers and bribe takers increase while the incomes of law-abiding citizens decrease. The most dangerous corruption is in the tax collection system, allowing the rich to evade them and shifting the tax burden onto the shoulders of poorer citizens.

| Table 4. FREQUENCY AND SIZE OF EXTORTION OF BRIBERES IN POST-SOCIALIST COUNTRIES in the late 1990s (according to studies by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the World Bank). | ||

| Countries | Percentage of firms that often pay bribes | Average percentage of bribes from the annual income of firms |

| Azerbaijan | 59,3 | 6,6 |

| Armenia | 40,3 | 6,8 |

| Belarus | 14,2 | 3,1 |

| Bulgaria | 23,9 | 3,5 |

| Hungary | 31,3 | 3,5 |

| Georgia | 36,8 | 8,1 |

| Kazakhstan | 23,7 | 4,7 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 26,9 | 5,5 |

| Lithuania | 23,2 | 4,2 |

| Moldova | 33,3 | 6,1 |

| Poland | 32,7 | 2,5 |

| Russia | 29,2 | 4,1 |

| Romania | 50,9 | 4,0 |

| Slovakia | 34,6 | 3,7 |

| Slovenia | 7,7 | 3,4 |

| Uzbekistan | 46,6 | 5,7 |

| Ukraine | 35,3 | 6,5 |

| Czech Republic | 26,3 | 4,5 |

| Croatia | 17,7 | 2,1 |

| Estonia | 12,9 | 2,8 |

Corrupt regimes are never “loved” by citizens and are therefore politically unstable. The ease of overthrowing the Soviet system in 1991 was largely due to the fact that the Soviet nomenklatura had a reputation as a thoroughly corrupt community, enjoying well-deserved contempt from ordinary citizens of the USSR. Since, however, in post-Soviet Russia the Soviet level of corruption was many times surpassed, this led to the low authority of the Boris Yeltsin regime in the eyes of the majority of Russians.

Participants in discussions about corruption, however, put forward the opinion that corruption has not only negative, but also positive consequences. Thus, in the first years after the collapse of the USSR, there was an opinion that if officials were allowed to take bribes, they would work more intensively, and corruption would help entrepreneurs bypass bureaucratic slingshots.

The concept of the beneficence of corruption does not take into account, however, the very high degree of lack of control that politicians and bureaucratic officials acquire in corrupt societies. They have the discretion to create and interpret instructions. In this case, instead of an incentive for more efficient activity, corruption becomes, on the contrary, an incentive for creating an excessive number of instructions. In other words, bribe takers deliberately create more and more new barriers in order to then “help” overcome them for an additional fee.

Corruption “apologists” also argue that bribery can reduce the time required to collect and process bureaucratic documents. But bribes do not necessarily speed up the speed of clerical work. It is known, for example, that in India, high-ranking civil servants take bribes in the following way: they do not promise the bribe-giver faster processing of his documents, but offer to slow down the process of processing documents for competing companies.

The argument that corruption is a stimulus for economic development is especially dangerous because it destroys law and order. Some Russian criminologists argue that in the early 1990s, in post-Soviet Russia, “with the best of intentions,” penalties for official abuses were actually temporarily abolished, and this led to an increase in bureaucratic extortion, which aggravated the economic crisis.

Fight against corruption.

Since state corruption has become one of the brakes on the development of not only individual countries, but also the world economy as a whole, it began to be considered, starting around the 1980s, as one of the main concerns of international politics.

Anti-corruption goals can be chosen in different ways: immediate increase in efficiency in the private sector, long-term dynamic efficiency of the economy, its growth, social justice, political stability. According to the chosen goal, the most appropriate anti-corruption measures are used.

Legislative reforms are often chosen as the simplest tool - not only and not so much the tightening of penalties for corruption, but the simplification and reduction of government control (reducing the frequency of inspections, lowering taxes) to reduce the very possibilities of abusing official position. The arsenal of government measures to combat corruption also includes fairly simple measures to simply tighten control. Post-Soviet Georgia, for example, has introduced a system under which government officials are required to declare their income when they take office, as well as when they leave office.

The international fight against corruption is seriously hampered by differences between the legal systems of different countries in the interpretation of corruption as an economic offense. Thus, in some countries (for example, Taiwan) only bribe takers are punished, and offering a bribe is not a criminal offense. In other countries (for example, in Chile) the situation is diametrically opposite: giving a bribe is a criminal offense, but receiving a bribe is not considered such, unless the official has committed other abuses. In addition to differences in the characteristics of a criminal corruption offense, there are strong differences in penalties for it.

While these measures must be implemented by the central government, they also require support from civil society. When the will of political leaders is based on active public support, it is possible to achieve strong changes in a fairly short period of time (as was the case in the 1990s in Italy during the Clean Hands campaign). On the contrary, if citizens place all their hopes on “wise rulers”, and themselves passively wait for the result, then the noisy campaign against corruption may end in an even greater increase (this is exactly what happened in our country in the early 1990s) or result in repression against political opponents of the ruling regime.

However, the legislative actions of the state cannot in principle bring a decisive turning point in the fight against corruption (if only because the fight against corruption can be “led” by corrupt officials themselves). Decisive success is possible only by increasing the state's dependence on citizens. This requires long-term institutional reforms such as reducing the number and size of government bodies and their staff, creating special or even independent institutions empowered to investigate allegations of corruption (such as the ombudsman institution in Sweden and some other countries), introducing systems of ethical standards for civil servants, etc. Finally, the fight against corruption is impossible without the help of voluntary whistleblowers. In the United States, an informant receives from 15 to 30% of the cost of material damage identified through his denunciation and is protected from persecution by the violators he exposed.

The possibility of implementing these measures depends not so much on the political will of the rulers, but on the culture of the governed society. For example, in Eastern countries with weak traditions of self-government, it is better to rely on the prestige and high pay of public service. This is exactly the path followed by Japan and the “Asian tigers” (especially Singapore and Hong Kong), where the high authority of government officials made it possible to create a highly efficient economic system with a relatively small administrative apparatus and low corruption. In Western countries, with their characteristic distrust of “state wisdom,” on the contrary, they often focus on the development of the actions of non-governmental organizations, civil self-government and control.

Successful fight against corruption, as economists prove, provides immediate benefits that many times exceed the costs associated with it. According to some estimates, spending one monetary unit (dollar, pound sterling, ruble...) on combating corruption brings on average 23 units when fighting corruption at the level of an individual country and about 250 when fighting it at the international level.

It is now generally accepted that neither individual countries nor international organizations can cope with corruption on their own, without helping each other. It is almost impossible to defeat corruption in a single country, since the resistance of the bureaucracy is too strong. Even if there is political will to suppress corruption, lack of practical experience, information and financial resources reduces its effectiveness. International organizations - such as the United Nations, the European Union, the World Bank, etc. - actively stimulate the fight against corruption, but they, with their experienced staff, awareness and large finances, cannot successfully combat corruption in any country if its government and citizens do not show the will and determination to fight. That is why this problem can only be resolved in close cooperation between individual countries and international organizations.

In the wake of the scandalous revelations in the Lockheed case, the United States passed the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act in 1977, under which American employees and officials were punished with fines or imprisonment for paying bribes to employees of other countries. Although this law was adopted in the hope that other investor countries would follow the example of the United States, this never happened. Only in February 1999, the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention, which was signed by 35 states, came into force, prohibiting the use of bribery in concluding foreign transactions. However, the dissemination of information about it was rather slow: when a survey was conducted in 2002 among managers of Third World countries actively working with foreign entrepreneurs, only 7% of respondents demonstrated good familiarity with the Convention, while 42% had not even heard of its existence .

Corruption in Russia.

Our history, as well as the history of other countries lagging behind in development, is characterized by a high level of corruption in the state apparatus.

Endemic bribery and theft of officials were first recognized as an obstacle to the development of the country back in the time of Peter I. There is a well-known historical anecdote: the emperor decided in the heat of the moment to issue a decree according to which any official who stole an amount equal to the price of a rope should be hanged; however, his associates unanimously declared that in this case the sovereign would be left without subjects. It is characteristic that Chief Fiscal Nesterov, who led the fight against embezzlement and bribery on the personal instructions of the emperor, was himself eventually executed for bribes. The mixing of the state treasury with the private pocket remained typical not only in the 18th, but also in the 19th century. Plot Inspector N.V. Gogol is based precisely on the fact that in Nikolaev Russia, officials of almost all ranks systematically abused their position and were constantly in fear of exposure. Only after the Great Reforms of the 1860s did the level of corruption in Russian officials begin to decrease, although it still remained above the “average European” level.

In the Soviet Union, the attitude towards corruption was rather ambivalent. On the one hand, abuse of official position was considered one of the most serious violations, since it undermined the authority of the Soviet government in the eyes of citizens. On the other hand, government managers very quickly formed in the USSR into a kind of state-class, opposed to “ordinary people” and not subject to their control. Therefore, on the one hand, Soviet legislation provided for much more severe punishments for bribe takers than in other countries - up to and including the death penalty. On the other hand, representatives of the nomenklatura were virtually immune from prosecution and were not too afraid of punishment. In the 1970s, corruption began to acquire a systemic, institutional character. Positions that provide wide scope for abuse have literally begun to be sold in some places. The shock from the abuses revealed at the highest level in the late 1980s (“Rashidov case”, “Churbanov case”) played a big role in the collapse of the Soviet regime.

Although the radical liberals led by B.N. Yeltsin came to power under the slogans of fighting abuses, once in power they themselves noticeably “blocked” the achievements of their predecessors. Surprised foreigners even stated that in Russia in the 1990s, “the majority of civil servants simply do not realize that personal enrichment in the service is a crime.” There were many reasons for such assessments. The fact is that the incomes of government officials remained quite modest, but at the same time it was almost impossible to do business without their favor. Particularly rich opportunities for abuse arose during privatization, when its organizers could literally “appoint as millionaires” the people they liked.

Researchers believe that the most negative feature of post-Soviet corruption is not so much the high intensity of extortion as its decentralized nature. If, for example, in China or Indonesia it is enough for an entrepreneur to “grease up” several high-ranking administrators, then in Russia he has to pay taxes into the pockets of not only them, but also the mass of “minor bosses” (such as sanitary and tax inspectors). As a result, the development of post-Soviet business has become very ugly.

A study conducted in 2000–2001 by the Informatics for Democracy Foundation showed that about 37 billion dollars are spent on bribes in Russia annually (about 34 billion for business bribes, 3 billion for everyday corruption), which is almost equal to income state budget of the country. Although this estimate was considered overestimated by some experts and underestimated by others, it shows the scale of post-Soviet corruption.

In the early 2000s, the Russian government began to demonstrate a desire to limit corruption, however, due to the wide scope of this phenomenon, it will apparently not be possible to reduce the level of corruption to average world standards any time soon.

Yuri Latov

Literature:

Raisman V.M. Hidden lies. Bribes: “crusades” and reforms. M., “Progress”, 1988

Levin M.Y., Tsirik M.L. Corruption as an object of mathematical modeling. – Economics and mathematical methods, 1998. Vol. 3.

Timofeev L.M. Institutional corruption. M., Russian State University for the Humanities, 2000

Satarov G.S., Parkhomenko S.A. Diversity of countries and diversity of corruption (Analysis of comparative studies). M., 2001

Rose-Ackerman S. Corruption and the state. Causes, consequences, reforms. M., “Logos”, 2003

Center for Anti-Corruption Research and Initiatives "Transparency International-R" (http://www.transparency.org.ru)

Corruption is not a myth, but a reality. But it is a myth that corruption is an exclusively Russian phenomenon.

The historical roots of corruption probably go back to the custom of giving gifts to gain favor. In primitive and early class societies, payment to a priest, chief or military commander for personally seeking their help was considered a universal norm. The offering distinguished the person from other petitioners and helped ensure that his request was fulfilled.

The situation began to change as the state apparatus became more complex and professionalized and the power of the central government increased. Professional officials appeared who, according to the plans of the rulers, should have been content only with a fixed salary. In practice, officials sought to take advantage of their position to secretly increase their income.

One of the oldest mentions of corruption is found in the cuneiform writings of ancient Babylon. As follows from deciphered texts dating back to the middle of the 3rd millennium BC. e., already then before the Sumerian king Urukagin The problem of suppressing the abuses of judges and officials who extorted illegal rewards was very acute. He went down in history as the first fighter against corruption who reformed public administration in order to suppress abuses on the part of the royal administration, judges, and temple staff, reduced and streamlined payments for rituals, and introduced severe penalties for bribery by officials. 13

The rulers of Ancient Egypt faced similar problems. Documents discovered during archaeological research also indicate massive manifestations of corruption in Jerusalem in the period after the Babylonian captivity of the Jews in 597 - 538. before the Nativity of Christ.

The first treatise condemning corruption - "Arthashastra" - was published under a pseudonym Kautilya one of the ministers of Bharata (India) in the 4th century. BC e. The ancient Indian author identified 40 means of theft of state property by greedy officials and sadly stated that “just as one cannot help but perceive honey if it is on the tongue, so the property of a king cannot be misappropriated, even if only a little, by those in charge of this property "

By order of the Persian king Cambyses, the new judge sat in a chair upholstered with leather taken from his predecessor, who was caught taking bribes.

Despite demonstrative and often brutal punishments for corruption, the fight against it did not lead to the desired results. At best, it was possible to prevent the most dangerous crimes,