Before considering the very essence of the history of the ancient Germans, it is necessary to define this section of historical science.

The history of the ancient Germans is a section of historical science that studies and tells the history of the Germanic tribes. This section covers the period from the creation of the first German states to the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

History of the ancient Germans

Origin of the ancient Germans

The ancient Germanic peoples as an ethnic group formed on the territory of Northern Europe. Their ancestors are considered to be Indo-European tribes who settled in Jutland, southern Scandinavia and in the Elbe River basin. Roman historians began to identify them as an independent ethnic group; the first mentions of the Germans as an independent ethnic group date back to monuments of the first century BC. From the second century BC, the tribes of the ancient Germans began to move south. Already in the third century AD, the Germans began to actively attack the borders of the Western Roman Empire.

Having first met the Germans, the Romans wrote about them as northern tribes distinguished by their warlike disposition. Much information about the Germanic tribes can be found in the works of Julius Caesar. The great Roman commander, having captured Gaul, moved west, where he had to engage in battle with the Germanic tribes. Already in the first century AD, the Romans collected information about the settlement of the ancient Germans, about their structure and morals.

During the first centuries of our era, the Romans waged constant wars with the Germans, but they were never able to completely conquer them. After unsuccessful attempts to completely capture their lands, the Romans went on the defensive and carried out only punitive raids.

In the third century, the ancient Germans were already threatening the existence of the empire itself. Rome gave some of its territories to the Germans, and went on the defensive in more successful territories. But a new, even greater threat from the Germans arose during the great migration of peoples, as a result of which hordes of Germans settled on the territory of the empire. The Germans never stopped raiding Roman villages, despite all the measures taken.

At the beginning of the fifth century, the Germans, under the command of King Alaric, captured and plundered Rome. Following this, other Germanic tribes began to move, they fiercely attacked the provinces, and Rome could not protect them, all forces were thrown into the defense of Italy. Taking advantage of this, the Germans captured Gaul, and then Spain, where they founded their first kingdom.

The ancient Germans also performed well in alliance with the Romans, defeating Attila’s army on the Catalaunian fields. After this victory, the Roman emperors began to appoint German leaders as their military commanders.

It was the Germanic tribes led by King Odoacer who destroyed the Roman Empire, deposing the last emperor, Romulus Augustus. On the territory of the captured empire, the Germans began to create their own kingdoms - the first early feudal monarchies of Europe.

Religion of the ancient Germans

All Germans were pagans, and their paganism was different, in different regions, it was very different from each other. However, most of the pagan deities of the ancient Germans were common, they were only called by different names. So, for example, the Scandinavians had a god Odin, and to the West Germans this deity was represented by the name Wotan.The priests of the Germans were women, as Roman sources say, they were gray-haired. The Romans say that the pagan rituals of the Germans were extremely cruel. The throats of prisoners of war were cut, and predictions were made on the decomposed entrails of prisoners.

The ancient Germans saw a special gift in women and also worshiped them. In their sources, the Romans confirm that each Germanic tribe could have its own unique rituals and its own gods. The Germans did not build temples for the gods, but dedicated any land to them (groves, fields, etc.).

Activities of the ancient Germans

Roman sources say that the Germans were mainly engaged in cattle breeding. They mainly raised cows and sheep. Their craft was only slightly developed. But they had high quality stoves, spears, and shields. Only selected Germans, that is, the nobility, could wear armor.The clothing of the Germans was mainly made from animal skins. Both men and women wore capes; the richest Germans could afford pants.

To a lesser extent, the Germans were engaged in agriculture, but they had fairly high-quality tools, they were made of iron. The Germans lived in large long houses (from 10 to 30 m), next to the house there were stalls for domestic animals.

Before the great migration of peoples, the Germans led a sedentary way of life and cultivated the land. The Germanic tribes never immigrated of their own free will. On their lands they grew grain crops: oats, rye, wheat, barley.

The migration of peoples forced them to flee their native territories and try their luck in the ruins of the Roman Empire.

The Germans are ancient tribes of the Indo-European language group who lived by the 1st century. BC e. between the North and Baltic Seas, the Rhine, Danube and Vistula and in Southern Scandinavia. In the 4th-6th centuries. The Germans played a major role in the great migration of peoples, captured most of the Western Roman Empire, forming a number of kingdoms - the Visigoths, Vandals, Ostrogoths, Burgundians, Franks, Lombards.

Nature

The lands of the Germans were endless forests mixed with rivers, lakes and swamps.

Classes

The main occupations of the ancient Germans were agriculture and cattle breeding. They also engaged in hunting, fishing and gathering. Their occupation was both war and the booty associated with it.

Vehicles

The Germans had horses, but in small numbers and in their training, the Germans did not achieve noticeable success. They also had carts. Some Germanic tribes had a fleet - small ships.

Architecture

The ancient Germans, who had just become sedentary, did not create significant architectural structures; they did not have cities. The Germans did not even have temples - religious rites were carried out in sacred groves. The dwellings of the Germans were made of untreated wood and coated with clay, and underground storerooms for supplies were dug in them.

Military affairs

The Germans mainly fought on foot. There were cavalry in small quantities. Their weapons were short spears (frames) and darts. Wooden shields were used for protection. Only the nobility had swords, armor and helmets.

Sport

The Germans played dice, considering it a serious activity, and so enthusiastically that they often lost everything to their opponent, including their own freedom at stake; in case of loss, such a player became the slave of the winner. One ritual is also known - young men, in front of spectators, jumped among swords and spears dug into the ground, showing their own strength and dexterity. The Germans also had something like gladiatorial fights - a captured enemy fought one on one with a German. However, this spectacle was basically in the nature of fortune-telling - the victory of one or another opponent was considered as an omen about the outcome of the war.

Arts and literature

Writing was unknown to the Germans. Therefore, their literature existed in oral form. Art was of an applied nature. The religion of the Germans forbade giving the gods a human form, so such areas as sculpture and painting were undeveloped among them.

Science

Science among the ancient Germans was not developed and was of an applied nature. The German household calendar divided the year into only two seasons - winter and summer. The priests had more accurate astronomical knowledge, who used it to calculate the time of holidays. Due to their passion for warfare, the ancient Germans probably had quite developed medicine - however, not at the level of theory, but exclusively in terms of practice.

Religion

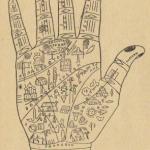

The religion of the ancient Germans was polytheistic in nature, in addition, each Germanic tribe, apparently, had its own cults. Religious ceremonies were performed by priests in sacred groves. Various fortune tellings were widely used, especially fortune telling with runes. There were sacrifices, including human ones.

The Germans as a people formed in northern Europe from Indo-European tribes that settled in Jutland, the lower Elbe and southern Scandinavia in the 1st century BC. The ancestral home of the Germans was Northern Europe, from where they began to move south. At the same time, they came into contact with the indigenous inhabitants - the Celts, who were gradually forced out. The Germans differed from the southern peoples in their tall stature, blue eyes, reddish hair color, and warlike and enterprising character.

The name "Germans" is of Celtic origin. Roman authors borrowed the term from the Celts. The Germans themselves did not have their own common name for all tribes. A detailed description of their structure and way of life is given by the ancient Roman historian Cornelius Tacitus at the end of the 1st century AD.

Germanic tribes are usually divided into three groups: North Germanic, West Germanic and East Germanic. Part of the ancient Germanic tribes - the northern Germans - moved along the ocean coast to the north of Scandinavia. These are the ancestors of modern Danes, Swedes, Norwegians and Icelanders.

The most significant group is the West Germans. They were divided into three branches. One of them is the tribes that lived in the Rhine and Weser regions. These included the Batavians, Mattiacs, Chatti, Cherusci and other tribes.

The second branch of the Germans included the tribes of the North Sea coast. These are the Cimbri, Teutons, Frisians, Saxons, Angles, etc. The third branch of the West German tribes was the cult union of the Germinons, which included the Suevi, Lombards, Marcomanni, Quadi, Semnones and Hermundurs.

These groups of ancient Germanic tribes conflicted with each other and this led to frequent disintegrations and new formations of tribes and unions. In the 3rd and 4th centuries AD. e. numerous individual tribes united into large tribal unions of the Alemanni, Franks, Saxons, Thuringians and Bavarians.

The main role in the economic life of the German tribes of this period belonged to cattle breeding, which was especially developed in areas abounding in meadows - Northern Germany, Jutland, Scandinavia.

The Germans did not have continuous, closely built-up villages. Each family lived in a separate farm, surrounded by meadows and groves. Kinship families formed a separate community (mark) and jointly owned the land. Members of one or more communities came together and held public assemblies. Here they made sacrifices to their gods, resolved issues of war or peace with their neighbors, dealt with litigation, judged criminal offenses and elected leaders and judges. Young men who reached adulthood received weapons from the people's assembly, which they never parted with.

Like all uneducated peoples, the ancient Germans led a harsh lifestyle, dressed in animal skins, armed themselves with wooden shields, axes, spears and clubs, loved war and hunting, and in peacetime indulged in idleness, dice games, feasts and drinking bouts. Since ancient times, their favorite drink was beer, which they brewed from barley and wheat. They loved the game of dice so much that they often lost not only all their property, but also their own freedom.

Caring for the household, fields and herds remained the responsibility of women, old people and slaves. Compared to other barbarian peoples, the position of women among the Germans was better and polygamy was not widespread among them.

During the battle, women were behind the army, they looked after the wounded, brought food to the fighters and reinforced their courage with their praise. Often the Germans, put to flight, were stopped by the cries and reproaches of their women, then they entered the battle with even greater ferocity. Most of all, they feared that their wives would not be captured and become slaves to their enemies.

The ancient Germans already had a division into classes: noble (edshzings), free (freelings) and semi-free (lassas). Military leaders, judges, dukes, and counts were chosen from the noble class. During wars, leaders enriched themselves with booty, surrounded themselves with a squad of the bravest people, and with the help of this squad acquired supreme power in their fatherland or conquered foreign lands.

The ancient Germans developed crafts, mainly weapons, tools, clothing, utensils. The Germans knew how to mine iron, gold, silver, copper, and lead. The technology and artistic style of handicrafts have undergone significant Celtic influences. Leather dressing and wood processing, ceramics and weaving were developed.

Trade with Ancient Rome played a significant role in the life of the ancient Germanic tribes. Ancient Rome supplied the Germans with ceramics, glass, enamel, bronze vessels, gold and silver jewelry, weapons, tools, wine, and expensive fabrics. Agricultural and livestock products, livestock, leather and skins, furs, as well as amber, which was in special demand, were imported into the Roman state. Many Germanic tribes had a special privilege of intermediary trade.

The basis of the political structure of the ancient Germans was the tribe. The People's Assembly, in which all armed free members of the tribe participated, was the highest authority. It met from time to time and resolved the most significant issues: the election of the leader of the tribe, the analysis of complex intra-tribal conflicts, initiation into warriors, the declaration of war and the conclusion of peace. The issue of relocating the tribe to new places was also decided at the tribe meeting.

At the head of the tribe was a leader who was elected by the people's assembly. In ancient authors it was designated by various terms: principes, dux, rex, which corresponds to the common German term könig - king.

A special place in the political structure of ancient Germanic society was occupied by military squads, which were formed not by clan, but on the basis of voluntary loyalty to the leader.

The squads were created for the purpose of predatory raids, robberies and military raids into neighboring lands. Any free German with a penchant for risk and adventure or profit, and with the abilities of a military leader, could create a squad. The law of life of the squad was unquestioning submission and devotion to the leader. It was believed that to emerge alive from a battle in which a leader fell was dishonor and disgrace for life.

The first major military clash of the Germanic tribes with Rome associated with the invasion of the Cimbri and Teutons, when in 113 BC. The Teutons defeated the Romans at Norea in Noricum and, devastating everything in their path, invaded Gaul. In 102-101. BC The troops of the Roman commander Gaius Marius defeated the Teutons at Aqua Sextiae, then the Cimbri at the Battle of Vercellae.

In the middle of the 1st century. BC Several Germanic tribes united and set out together to conquer Gaul. Under the leadership of the king (tribal leader) Areovists, the German Suevi tried to gain a foothold in Eastern Gaul, but in 58 BC. were defeated by Julius Caesar, who expelled Ariovist from Gaul, and the union of tribes disintegrated.

After Caesar's triumph, the Romans repeatedly invaded and fought in German territory. An increasing number of Germanic tribes find themselves in the zone of military conflicts with Ancient Rome. These events are described by Gaius Julius Caesar in

Under Emperor Augustus, an attempt was made to expand the borders of the Roman Empire east of the Rhine. Drusus and Tiberius conquered the tribes in the north of modern Germany and built camps on the Elbe. In the 9th year AD. Arminius - the leader of the German Cherusci tribe defeated the Roman legions in the Teutonic forest and for some time restored the former border along the Rhine.

The Roman commander Germanicus avenged this defeat, but soon the Romans stopped further conquest of German territory and established border garrisons along the Cologne-Bonn-Ausburg line to Vienna (modern names).

At the end of the 1st century. the border was determined - "Roman Frontiers"(lat. Roman Lames) separating the population of the Roman Empire from the diverse “barbarian” Europe. The border ran along the Rhine, Danube and Limes, which connected these two rivers. It was a fortified strip with fortifications along which troops were stationed.

Part of this line from the Rhine to the Danube, 550 km long, still exists and, as an outstanding monument of ancient fortifications, was included in the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1987.

But let's go back to the distant past to the ancient Germanic tribes, which united when they began wars with the Romans. Thus, several strong peoples gradually formed - the Franks on the lower reaches of the Rhine, the Alemanni to the south of the Franks, the Saxons in Northern Germany, then the Lombards, Vandals, Burgundians and others.

The easternmost Germanic people were the Goths, who were divided into Ostrogoths and Visigoths - eastern and western. They conquered the neighboring peoples of the Slavs and Finns, and during the reign of their king Germanaric they dominated from the Lower Danube to the very banks of the Don. But the Goths were driven out from there by the wild people who came from beyond the Don and Volga - the Huns. The invasion of the latter was the beginning The Great Migration of Peoples.

Thus, in the diversity and diversity of historical events and the seeming chaos of inter-tribal alliances and conflicts between them, treaties and clashes between the Germans and Rome, the historical foundation of those subsequent processes that formed the essence of the Great Migration emerges →

The name of the Germans aroused bitter feelings in the Romans and evoked dark memories in their imagination. From the time when the Teutons and Cimbri crossed the Alps and rushed in a devastating avalanche onto beautiful Italy, the Romans looked with alarm at the peoples little known to them, worried about the continuous movements in Ancient Germany beyond the ridge fencing Italy from the north. Even Caesar's brave legions were overcome with fear when he led them against the Suevi of Ariovistus. The fear of the Romans was increased by the terrible news of the defeat of Varus in the Teutoburg Forest, the stories of soldiers and prisoners about the harshness of the German country, the savagery of its inhabitants, their high stature, and human sacrifices. Residents of the south, the Romans, had the darkest ideas about Ancient Germany, about impenetrable forests that stretch from the banks of the Rhine for a nine-day journey east to the upper reaches of the Elbe and the center of which is the Hercynian Forest, filled with unknown monsters; about the swamps and desert steppes that extend in the north to the stormy sea, over which there are thick fogs that do not allow the life-giving rays of the sun to reach the earth, on which the marsh and steppe grass is covered with snow for many months, along which there are no paths from the region of one people to the region another. These ideas about the severity and gloom of Ancient Germany were so deeply rooted in the thoughts of the Romans that even the impartial Tacitus says: “Whoever would leave Asia, Africa or Italy to go to Germany, a country of a harsh climate, devoid of all beauty, making an unpleasant impression on everyone, living in it or visiting it, if it is not his homeland? The prejudices of the Romans against Germany were strengthened by the fact that they considered all those lands that lay beyond the borders of their state to be barbaric and wild. So, for example, Seneca says: “Think about those peoples who live outside the Roman state, about the Germans and about the tribes wandering along the lower Danube; Isn’t an almost continuous winter weighing down on them, a constantly cloudy sky, isn’t the food that the unfriendly, barren soil gives them scanty?”

Family of ancient Germans

Meanwhile, near the majestic oak and leafy linden forests, fruit trees were already growing in Ancient Germany and there were not only steppes and moss-covered swamps, but also fields abundant in rye, wheat, oats, and barley; ancient Germanic tribes already extracted iron from the mountains for weapons; healing warm waters were already known in Matthiak (Wiesbaden) and in the land of the Tungras (in Spa or Aachen); and the Romans themselves said that in Germany there are a lot of cattle, horses, a lot of geese, the down of which the Germans use for pillows and feather beds, that Germany is rich in fish, wild birds, wild animals suitable for food, that fishing and hunting provide the Germans with tasty food. I'm going. Only gold and silver ores in the German mountains were not yet known. “The gods denied them silver and gold—I don’t know how to say, whether out of mercy or hostility toward them,” says Tacitus. Trade in Ancient Germany was only barter, and only the tribes neighboring the Roman state used money, of which they received a lot from the Romans for their goods. The princes of ancient Germanic tribes or people who traveled as ambassadors to the Romans had gold and silver vessels received as gifts; but, according to Tacitus, they valued them no more than clay ones. The fear that the ancient Germans initially instilled in the Romans later turned into surprise at their tall stature, physical strength, and respect for their customs; the expression of these feelings is “Germania” by Tacitus. Upon completion wars of the era of Augustus and Tiberius relations between the Romans and the Germans became close; educated people traveled to Germany and wrote about it; this smoothed out many of the previous prejudices, and the Romans began to judge the Germans better. Their concepts of the country and climate remained the same, unfavorable, inspired by the stories of merchants, adventurers, returning captives, exaggerated complaints of soldiers about the difficulties of campaigns; but the Germans themselves began to be considered by the Romans as people who had a lot of good things in them; and finally, the fashion arose among the Romans to make their appearance, if possible, similar to the German one. The Romans admired the tall stature and slender, strong physique of the ancient Germans and German women, their flowing golden hair, light blue eyes, in whose gaze pride and courage were expressed. Noble Roman women used artificial means to give their hair the color that they so liked in the women and girls of Ancient Germany.

In peaceful relations, the ancient Germanic tribes inspired respect in the Romans with courage, strength, and belligerence; those qualities that made them terrible in battles turned out to be respectable when making friends with them. Tacitus extols the purity of morals, hospitality, straightforwardness, fidelity to his word, marital fidelity of the ancient Germans, their respect for women; he praises the Germans to such an extent that his book about their customs and institutions seems to many scholars to have been written with the purpose that his pleasure-loving, vicious fellow tribesmen would be ashamed when reading this description of a simple, honest life; they think that Tacitus wanted to clearly characterize the depravity of Roman morals by depicting the life of Ancient Germany, which represented the direct opposite of them. And indeed, in his praise of the strength and purity of marital relations among the ancient Germanic tribes, one can hear sadness about the depravity of the Romans. In the Roman state, the decline of the former excellent state was visible everywhere, it was clear that everything was leaning towards destruction; the brighter the life of Ancient Germany, which still preserved primitive customs, was pictured in Tacitus’s thoughts. His book is imbued with a vague premonition that Rome is in great danger from a people whose wars are etched in the memory of the Romans more deeply than the wars with the Samnites, Carthaginians and Parthians. He says that “more triumphs were celebrated over the Germans than victories were won”; he foresaw that the black cloud on the northern edge of the Italian horizon would burst over the Roman state with new thunderclaps, stronger than the previous ones, because “the freedom of the Germans is more powerful than the strength of the Parthian king.” The only consolation for him is the hope for the discord of the ancient Germanic tribes, for the mutual hatred between their tribes: “Let the Germanic peoples remain, if not love for us, then the hatred of some tribes for others; given the dangers threatening our state, fate cannot give us anything better than discord between our enemies.”

The settlement of the ancient Germans according to Tacitus

Let us combine the features that Tacitus describes in his “Germania” as the way of life, customs, and institutions of the ancient Germanic tribes; he makes these notes fragmentarily, without strict order; but, putting them together, we get a picture in which there are many gaps, inaccuracies, misunderstandings, either of Tacitus himself, or of the people who provided him with information, much is borrowed from folk tradition, which has no reliability, but which still shows us the main features of life Ancient Germany, the germs of what later developed. The information that Tacitus gives us, supplemented and clarified by the news of other ancient writers, legends, considerations of the past based on later facts, serves as the basis for our knowledge of the life of the ancient Germanic tribes in primitive times.

Hutt tribe

The lands to the northeast of the Mattiacs were inhabited by the ancient Germanic tribe of the Hutts (Chazzi, Hazzi, Hessians - Hessians), whose country extended to the borders of the Hercynian Forest. Tacitus says that the Chatti were of a dense, strong build, that they had a courageous look, and a more active mind than other Germans; judging by German standards, the Hutts have a lot of prudence and intelligence, he says. Among them, a young man, having reached adulthood, did not cut his hair or shave his beard until he killed an enemy: “only then does he consider himself to have paid the debt for his birth and upbringing, worthy of his fatherland and parents,” says Tacitus.

Under Claudius, a detachment of German-Hattians made a predatory raid on the Rhine, in the province of Upper Germany. Legate Lucius Pomponius sent vangiones, nemetes and a detachment of cavalry under the command of Pliny the Elder to cut off the retreat of these robbers. The warriors went very diligently, dividing into two detachments; one of them caught the Hutts returning from the robbery when they took a rest and got so drunk that they were unable to defend themselves. This victory over the Germans was, according to Tacitus, all the more joyful because on this occasion several Romans who had been captured forty years earlier during the defeat of Varus were freed from slavery. Another detachment of the Romans and their allies went into the land of the Chatti, defeated them and, having collected a lot of booty, returned to Pomponius, who stood with the legions on Tauna, ready to repel the Germanic tribes if they wanted to take revenge. But the Hutts feared that when they attacked the Romans, the Cherusci, their enemies, would invade their land, so they sent ambassadors and hostages to Rome. Pomponius was more famous for his dramas than for his military exploits, but for this victory he received a triumph.

Ancient Germanic tribes of Usipetes and Tencteri

The lands north of Lahn, along the right bank of the Rhine, were inhabited by the ancient Germanic tribes of the Usipetes (or Usipians) and Tencteri. The Tencteri tribe was famous for its excellent cavalry; Their children had fun with horseback riding, and old people also loved to ride. The father's war horse was inherited by the bravest of his sons. Further to the northeast along the Lippe and the upper reaches of the Ems lived the Bructeri, and behind them, east to the Weser, the Hamavs and Angrivars. Tacitus heard that the Bructeri had a war with their neighbors, that the Bructeri were driven out of their land and almost completely exterminated; this civil strife was, in his words, “a joyful spectacle for the Romans.” It is probable that the Marsi, a brave people exterminated by Germanicus, formerly lived in the same part of Germany.

Frisian tribe

The lands along the seashore from the mouth of the Ems to the Batavians and Caninefates were the area of settlement of the ancient German Frisian tribe. The Frisians also occupied neighboring islands; these swampy places were not enviable to anyone, says Tacitus, but the Frisians loved their homeland. They obeyed the Romans for a long time, not caring about their fellow tribesmen. In gratitude for the protection of the Romans, the Frisians gave them a certain number of ox hides for the needs of the army. When this tribute became burdensome due to the greed of the Roman ruler, this Germanic tribe took up arms, defeated the Romans, and overthrew their power (27 A.D.). But under Claudius, the brave Corbulo managed to return the Frisians to an alliance with Rome. Under Nero (58 AD) a new quarrel began due to the fact that the Frisians occupied and began to cultivate some areas on the right bank of the Rhine that lay empty. The Roman ruler ordered them to leave there, they did not listen and sent two princes to Rome to ask that this land be left behind them. But the Roman ruler attacked the Frisians who settled there, destroyed some of them, and took others into slavery. The land occupied by them became desert again; soldiers of neighboring Roman detachments allowed their cattle to graze on it.

Hawk tribe

To the east from the Ems to the lower Elbe and inland to the Chatti lived the ancient Germanic tribe of the Chauci, whom Tacitus calls the noblest of the Germans, who placed justice as the basis of their power; he says: “They have neither greed for conquest nor arrogance; they live calmly, avoiding quarrels, do not provoke anyone to war with insults, do not devastate or plunder neighboring lands, do not seek to base their dominance on insults to others; this best testifies to their valor and strength; but they are all ready for war, and when the need arises, their army is always under arms. They have a lot of warriors and horses, their name is famous even if they love peace.” This praise does not fit well with the news reported by Tacitus himself in the Chronicle that the Chauci in their boats often went to rob ships sailing along the Rhine and neighboring Roman possessions, that they drove out the Ansibars and took possession of their land.

Cherusci Germans

To the south of the Chauci lay the land of the ancient Germanic tribe of the Cherusci; this brave people, who heroically defended freedom and their homeland, had already lost their former strength and glory during the time of Tacitus. Under Claudius, the Cherusci tribe called Italicus, the son of Flavius and nephew of Arminius, a handsome and brave young man, and made him king. At first he ruled kindly and fairly, then, driven out by his opponents, he defeated them with the help of the Lombards and began to rule cruelly. We have no news about his further fate. Weakened by discord and having lost their belligerence from a long peace, the Cherusci during the time of Tacitus had no power and were not respected. Their neighbors, the Phosian Germans, were also weak. About the Cimbri Germans, whom Tacitus calls a tribe of small numbers, but famous for their exploits, he only says that in the time of Marius they inflicted many heavy defeats on the Romans and that the extensive camps left from them on the Rhine show that they were then very numerous.

Suebi tribe

The ancient Germanic tribes who lived further east between the Baltic Sea and the Carpathians, in a country very little known to the Romans, are called by Tacitus, like Caesar, by the common name Sueves. They had a custom that distinguished them from other Germans: free people combed their long hair up and tied it above the crown, so that it fluttered like a plume. They believed that this made them more dangerous to their enemies. There has been a lot of research and debate about which tribes the Romans called Suevi, and about the origin of this tribe, but given the darkness and contradictory information about them among ancient writers, these questions remain unresolved. The simplest explanation for the name of this ancient Germanic tribe is that "Sevi" means nomads (schweifen, "to wander"); The Romans called all those numerous tribes who lived far from the Roman border behind dense forests Suevi, and believed that these Germanic tribes were constantly moving from place to place, because they most often heard about them from the tribes they drove to the west. The Romans' information about the Suevi is inconsistent and borrowed from exaggerated rumors. They say that the Suevi tribe had a hundred districts, from which each could field a large army, that their country was surrounded by desert. These rumors supported the fear that the name of the Suevi had already inspired in Caesar’s legions. Without a doubt, the Suevi were a federation of many ancient Germanic tribes, closely related to each other, in which the former nomadic life had not yet been completely replaced by a sedentary one, cattle breeding, hunting and war still prevailed over agriculture. Tacitus calls the Semnonians, who lived on the Elbe, the most ancient and noblest of them, and the Lombards, who lived north of the Semnonians, the bravest.

Hermundurs, Marcomanni and Quads

The area east of the Decumat region was inhabited by the ancient Germanic tribe of the Hermundurs. These loyal allies of the Romans enjoyed great confidence and had the right to trade freely in the main city of the Rhaetian province, present-day Augsburg. Below the Danube to the east lived a tribe of Germanic Narisci, and behind the Narisci there were Marcomanni and Quadi, who retained the courage that the possession of their land had given them. The areas of these ancient Germanic tribes formed the stronghold of Germany on the Danube side. The descendants of the Marcomanni were kings for quite a long time Maroboda, then foreigners who received power through the influence of the Romans and held on thanks to their patronage.

East Germanic tribes

The Germans who lived beyond the Marcomanni and Quadi had tribes of non-Germanic origin as their neighbors. Of the peoples who lived there in the valleys and gorges of the mountains, Tacitus classifies some as Suevi, for example, the Marsigni and Boers; others, such as the Gotins, he considers to be Celts because of their language. The ancient Germanic tribe of the Gotins was subject to the Sarmatians, extracted iron from their mines for their masters and paid them tribute. Behind these mountains (Sudetes, Carpathians) lived many tribes classified by Tacitus as Germans. Of these, the most extensive area was occupied by the Germanic tribe of the Lygians, who probably lived in present-day Silesia. The Lygians formed a federation to which, besides various other tribes, the Garians and Nagarwals belonged. To the north of the Lygians lived the Germanic Goths, and behind the Goths the Rugians and Lemovians; the Goths had kings who had more power than the kings of other ancient Germanic tribes, but still not so much that the freedom of the Goths was suppressed. From Pliny and Ptolemy we know that in the north-east of Germany (probably between the Wartha and the Baltic Sea) lived the ancient Germanic tribes of the Burgundians and Vandals; but Tacitus does not mention them.

Germanic tribes of Scandinavia: Swions and Sitons

The tribes living on the Vistula and the southern shore of the Baltic Sea closed the borders of Germany; to the north of them, on a large island (Scandinavia), lived the Germanic Swions and Sitons, strong in addition to the ground army and fleet. Their ships had bows at both ends. These tribes differed from the Germans in that their kings had unlimited power and did not leave weapons in their hands, but kept them in storerooms guarded by slaves. The Sitons, in the words of Tacitus, stooped to such servility that they were commanded by the queen, and they obeyed the woman. Beyond the land of the Svion Germans, says Tacitus, there is another sea, the water in which is almost motionless. This sea encloses the extreme limits of the lands. In the summer, after sunset, its radiance there still retains such strength that it darkens the stars all night.

Non-Germanic tribes of the Baltic states: Estii, Pevkini and Finns

The right bank of the Suevian (Baltic) Sea washes the land of the Estii (Estonia). In customs and clothing, the Estii are similar to the Suevi, and in language, according to Tacitus, they are closer to the British. Iron is rare among them; Their usual weapon is a mace. They are engaged in agriculture more diligently than the lazy Germanic tribes; they also sail on the sea, and they are the only people who collect amber; they call it glaesum (German glas, “glass”?) They collect it in the shallows of the sea and on the shore. For a long time they left it lying between other objects that the sea throws up; but Roman luxury finally drew their attention to it: “they themselves do not use it, they export it unprocessed and are amazed that they receive payment for it.”

After this, Tacitus gives the names of the tribes, about which he says that he does not know whether he should classify them as Germans or Sarmatians; these are the Wends (Vends), Pevkins and Fennas. He says about the Wends that they live by war and robbery, but differ from the Sarmatians in that they build houses and fight on foot. About the singers, he says that some writers call them bastarns, that in language, clothing, and the appearance of their dwellings they are similar to the ancient Germanic tribes, but that, having mixed through marriage with the Sarmatians, they learned from them laziness and untidiness. Far in the north live the Fenne (Finns), the most extreme people of the inhabited space of the earth; they are complete savages and live in extreme poverty. They have neither weapons nor horses. The Finns eat grass and wild animals, which they kill with arrows tipped with sharp bones; they dress in animal skins and sleep on the ground; to protect themselves from bad weather and predatory animals, they make themselves fences from branches. This tribe, says Tacitus, is not afraid of either people or gods. It has achieved what is most difficult for humans to achieve: they do not need to have any desires. Behind the Finns, according to Tacitus, lies a fabulous world.

No matter how great the number of ancient Germanic tribes was, no matter how great the difference in social life was between the tribes that had kings and those that did not, the insightful observer Tacitus saw that they all belonged to one national whole, that they were parts of a great people who, without mixing with foreigners, he lived according to completely original customs; the fundamental sameness was not smoothed over by tribal differences. The language, character of the ancient Germanic tribes, their way of life and the veneration of common Germanic gods showed that they all had a common origin. Tacitus says that in old folk songs the Germans praise the god Tuiscon and his son Mann, who was born from the earth, as their ancestors, that from the three sons of Mann three indigenous groups arose and received their names, which covered all the ancient Germanic tribes: Ingevones (Friesians), Germinons (Sevi) and Istevoni. In this legend of German mythology, the testimony of the Germans themselves survived under the legendary shell that, despite all their fragmentation, they did not forget the commonality of their origin and continued to consider themselves fellow tribesmen

Mysterious people in the darkness of the past: Germanic tribes. The Romans called them savages, far from culture. Did they know about anything other than battles and wars? What did they believe? What were they afraid of? How did you coexist with? What did they leave behind and what do we know about them? Who were the Germans?

Battle of Ariovistus with Caesar

October 1935. Archaeologists explore a burial mound on a Danish island. The hill dates back to the 1st century BC, time of the Germanic tribes.

Archaeologists make a sensational discovery: this grave of a Germanic priestess. This is evidenced by the found plant seeds, fossilized sea urchins and willow twigs - all this supposedly had magical meaning.

Archaeologists make a sensational discovery: this grave of a Germanic priestess. This is evidenced by the found plant seeds, fossilized sea urchins and willow twigs - all this supposedly had magical meaning.

Who the deceased was is unknown, because the biographies of German women of that era have not reached us. But Roman historians already mentioned the great influence that the priestesses had on the Germans.

Today, ancient sources and modern science allow us to tell about the life of the German priestess. Let's call her Bazin, and this is her story.

“The threat of war with the Romans looms over our tribe. I asked: should we fight? What will the signs say? The twigs of the sacred willow will predict my future. The fate of my tribe is in the hands of the gods. What will they tell us? And here's a word of caution: no fighting while Luna is dying. Let the weapon rest until the new moon."

But in 58 BC. roman general Caesar invaded the lands of the Sueves. Mindful of the warnings of the gods, Ariovistus was ready to negotiate with the Romans, but Caesar demanded that he leave his lands.

But in 58 BC. roman general Caesar invaded the lands of the Sueves. Mindful of the warnings of the gods, Ariovistus was ready to negotiate with the Romans, but Caesar demanded that he leave his lands.

Drusus set up Roman landmarks where no one even knew Rome existed. And here is what the Roman writes: “Drusus conquered most of the Germans and shed a lot of their blood.”

Like Drusus, Tiberius too Emperor's adopted son, and he had to fulfill the will of his father Augustus: finally conquer all the Germans.

Tiberius chose a different strategy than his brother: he decided not to achieve his goal by war. Tiberius took the path of diplomacy: The Germans had to voluntarily recognize the dominance of Rome. The resistance of the barbarians was to be broken by the cultural superiority of the Romans.

On the Rhine, on the site today, this began. A city arose according to the Roman model - a Germanic tribe that was an ally of Rome for many decades. Oppidum Ubiorum became one of the most luxurious imperial metropolises: theaters, temples and baths were supposed to convince the Germans of advantages of Roman civilization.

Not much has survived from the founding of Cologne. Earliest archaeological evidence – famous monument to the murders, the foundation of a stone tower built in 4 AD.

Having erected the tower, the Romans surrounded it with cut stone - this was the Roman method of construction. The city has become a gift from the emperor his German subjects. Apparently, the stone tower was part of the city wall of the Oppidum Ubiorum.

Having erected the tower, the Romans surrounded it with cut stone - this was the Roman method of construction. The city has become a gift from the emperor his German subjects. Apparently, the stone tower was part of the city wall of the Oppidum Ubiorum.

Rome had big plans for the city of the Ubii: the first main temple of the new province of Germany arose here. Once a year, all the conquered tribes of the Germans were supposed to gather here to renew their alliance with Rome.

The spacious temple, built by the Romans, towered over the city. A German priest led the ceremonies at the altar Ara Germany. It is symbolic that the altar was facing east, towards Germany - where Rome wanted to gain dominance.

Not only the Ubii, but also the tribes from the right bank of the Rhine gradually submitted to the Roman emperor. Presumably in 8 BC. gave up and... Like the rest of the tribes who lived between the Rhine and Elbe, they could either hide in the forest or choose between a hopeless fight and conquest. The leaders of the Cherusci decided on peaceful coexistence with Rome. Here is what the Roman author Paterculus writes: “Tiberius, as a winner, marched through all corners of Germany, without losing a single person from his loyal troops. He completely conquered the Germans, making them a tribute-paying province."

Rome was interested in making peace. Tiberius had to defend the newly acquired areas and seek a reliable alliance with the vanquished. This policy of appeasement turned out to be successful and long-lasting.

But the Cherusci paid a high price for peace and security: They had to give up their freedom, follow the orders of Rome, pay tribute and send their sons to serve in the Roman army.

"And in the end the Romans demanded the leader's son as a special guarantee of our devotion. The Romans called it . As a hostage, he had to go with the legionnaires to Rome. The leader gave in; he had no choice. The fate of our tribe was at stake. He was responsible for our freedom."

Children as hostages were commonplace in ancient times. They had to prove the loyalty of their tribes far from their homeland. In Rome, hostages were generally treated well. Arminius was raised as a Roman in the capital of the empire.

“Loyal comrades-in-arms accompanied the leader’s son to a foreign land. Will they ever see the lands of the Cherusci again?

20 years later Arminius returned to his homeland, and a dramatic turn took place in the history of the Germans...