Peter I The Great (Peter I) Russian Tsar from 1682 (ruled from 1689), the first Russian emperor (from 1721), the youngest son of Alexei Mikhailovich from his second marriage to Natalya Kirillovna Naryshkina.

Peter I was born June 9 (May 30, old style) 1672, in Moscow. On March 22, 1677, at the age of 5, he began to study.

According to old Russian custom, Peter began to be taught at the age of five. The Tsar and the Patriarch came to the opening of the course, served a prayer service with the blessing of water, sprinkled holy water on the new spude and, after blessing him, sat him down to learn the alphabet. Nikita Zotov bowed to his student and began his course of study, and immediately received a fee: the patriarch gave him one hundred rubles (more than a thousand rubles in our money), the sovereign granted him a court, promoted him to the nobility, and the queen mother sent two pairs of rich outer and underdresses and “the whole outfit,” into which Zotov immediately dressed up after the departure of the sovereign and patriarch. Krekshin also noted the day when Peter's education began - March 12, 1677, when, therefore, Peter was not even five years old.

He who is cruel is not a hero.

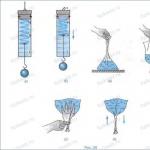

The prince studied willingly and smartly. In his spare time, he loved to listen to different stories and look at books with “kunsts” and pictures. Zotov told the queen about this, and she ordered him to give him “historical books”, manuscripts with drawings from the palace library, and ordered several new illustrations from the masters of painting in the Armory Chamber.

Noticing when Peter began to get tired of reading books, Zotov took the book from his hands and showed him these pictures, accompanying the review with explanations.

Peter I carried out public administration reforms (created Senate, collegiums, bodies of higher state control and political investigation; the church is subordinate to the state; The country was divided into provinces, a new capital was built - St. Petersburg).

Money is the artery of war.

Peter I used the experience of Western European countries in the development of industry, trade, and culture. He pursued a policy of mercantilism (the creation of manufactories, metallurgical, mining and other factories, shipyards, piers, canals). He supervised the construction of the fleet and the creation of a regular army.

Peter I led the army in the Azov campaigns of 1695-1696, the Northern War of 1700-1721, the Prut campaign of 1711, the Persian campaign of 1722-1723; commanded troops during the capture of Noteburg (1702), in the battles of the village of Lesnoy (1708) and near Poltava (1709). Contributed to strengthening the economic and political position of the nobility.

On the initiative of Peter I, many were opened educational institutions, Academy of Sciences, adopted the civil alphabet. The reforms of Peter I were carried out by cruel means, through extreme strain of material and human forces (poll tax), which entailed uprisings (Streletskoye 1698, Astrakhan 1705-1706, Bulavinskoye 1707-1709), which were mercilessly suppressed by the government. Being the creator of a powerful absolutist state, he achieved recognition of Russia as a great power.

Childhood, youth, education of Peter I

For confession there is forgiveness, for concealment there is no pardon. It is better to have an open sin than a hidden one.

Having lost his father in 1676, Peter was raised until the age of ten under the supervision of the Tsar’s elder brother Fyodor Alekseevich, who chose clerk Nikita Zotov as his teacher, who taught the boy to read and write. When Fedor died in 1682, the throne was to be inherited by Ivan Alekseevich, but since he was in poor health, the Naryshkin supporters proclaimed Peter Tsar. However, the Miloslavskys, relatives of Alexei Mikhailovich’s first wife, did not accept this and provoked a Streltsy riot, during which ten-year-old Peter witnessed a brutal massacre of people close to him. These events left an indelible mark on the boy’s memory, affecting both his mental health and his worldview.

The result of the rebellion was a political compromise: Ivan and Peter were placed on the throne together, and their elder sister, Princess Sofya Alekseevna, was named ruler. From that time on, Peter and his mother lived mainly in the villages of Preobrazhenskoye and Izmailovo, appearing in the Kremlin only to participate in official ceremonies, and their relationship with Sophia became increasingly hostile. The future tsar received neither secular nor church systematic education. He was left to his own devices and, active and energetic, spent a lot of time playing with his peers. Later, he was allowed to create his own “amusing” regiments, with which he played out battles and maneuvers and which later became the basis of the Russian regular army.

In Izmailovo, Peter discovered an old English boat, which, on his orders, was repaired and tested on the Yauza River. Soon he ended up in the German settlement, where he first became acquainted with European life, experienced his first passions and made friends among European merchants. Gradually, a company of friends formed around Peter, with whom he spent everything free time. In August 1689, when he heard rumors that Sophia was preparing a new Streltsy rebellion, he fled to the Trinity-Sergius Monastery, where loyal regiments and part of the court arrived from Moscow. Sophia, feeling that strength was on her brother’s side, made an attempt at reconciliation, but it was too late: she was removed from power and imprisoned in the Novodevichy Convent. Sophia was supported by her favorite - Fyodor Leontievich Shaklovity, who was executed under torture when Peter came to power.

Beginning of independent rule

To be afraid of misfortune is to see no happiness.

In the second half of the 17th century. Russia was experiencing a deep crisis associated with its socio-economic lag behind the advanced countries of Europe. Peter, with his energy, inquisitiveness, and interest in everything new, turned out to be a person capable of solving the problems facing the country. But at first he entrusted the management of the country to his mother and uncle, L.K. Naryshkin. The Tsar still visited Moscow little, although in 1689, at the insistence of his mother, he married E. F. Lopukhina.

Peter was attracted by sea fun, and he went for a long time to Pereslavl-Zalessky and Arkhangelsk, where he participated in the construction and testing of ships. Only in 1695 did he decide to undertake a real military campaign against the Turkish fortress of Azov. The first Azov campaign ended in failure, after which a fleet was hastily built in Voronezh, and during the second campaign (1696) Azov was taken. Taganrog was founded at the same time. This was the first victory of young Peter, which significantly strengthened his authority.

Soon after returning to the capital, the tsar went abroad (1697) with the Great Embassy. Peter visited Holland, England, Saxony, Austria and Venice, studied shipbuilding while working in shipyards, and became acquainted with the technical achievements of Europe at that time, its way of life, and its political structure. During his trip abroad the foundation was laid for the alliance of Russia, Poland and Denmark against Sweden. The news of a new Streltsy revolt forced Peter to return to Russia (1698), where he dealt with the rebels with extraordinary cruelty (Streltsy uprising of 1698).

The first transformations of Peter I

Peace is good, but at the same time you shouldn’t sleep, so as not to tie your hands, and so that the soldiers don’t become women.

Abroad, Peter’s political program basically took shape. Its ultimate goal was the creation of a regular police state based on universal service; the state was understood as the “common good.” The tsar himself considered himself the first servant of the fatherland, who was supposed to teach his subjects by his own example. Peter's unconventional behavior, on the one hand, destroyed the centuries-old image of the sovereign as a sacred figure, and on the other hand, it aroused protest among part of society (primarily the Old Believers, whom Peter cruelly persecuted), who saw the Antichrist in the tsar.

The reforms of Peter I began with the introduction of foreign dress and the order to shave the beards of everyone except peasants and the clergy. So, initially, Russian society turned out to be divided into two unequal parts: one (the nobility and the elite of the urban population) was intended to have a Europeanized culture imposed from above, the other preserved the traditional way of life.

In 1699, a calendar reform was also carried out. A printing house was created in Amsterdam to publish secular books in Russian, and the first Russian order was founded - St. Andrew the First-Called Apostle. The country was in dire need of its own qualified personnel, and the king ordered young men from noble families to be sent abroad to study. In 1701, the Navigation School was opened in Moscow. The reform of city government also began. After the death of Patriarch Adrian in 1700, a new patriarch was not elected, and Peter created the Monastic Order to manage the church economy. Later, instead of the patriarch, a synodal government of the church was created, which remained until 1917. Simultaneously with the first transformations, preparations for war with Sweden were intensively underway, for which a peace treaty with Turkey was previously signed.

Peter I also introduced the celebration of the New Year in Rus'.

Lessons from the Northern War

The war, the main goal of which was to consolidate Russia in the Baltic, began with the defeat of the Russian army near Narva in 1700. However, this lesson served Peter well: he realized that the reason for the defeat was primarily the backwardness of the Russian army, and with even greater energy he set about rearming it and the creation of regular regiments, first by collecting “dacha people”, and from 1705 by introducing conscription (in 1701, after the defeat of the Russian army near Narva, economist and publicist Ivan Tikhonovich Pososhkov compiled a note for Peter I “On military behavior”, proposing measures to create a combat-ready army.). The construction of metallurgical and weapons factories began, supplying the army with high-quality cannons and small arms. The campaign of Swedish troops led by King Charles XII to Poland allowed the Russian army to win its first victories over the enemy, capture and devastate a significant part of the Baltic states. In 1703, at the mouth of the Neva, Peter founded St. Petersburg - the new capital of Russia, which, according to the Tsar’s plan, was to become an exemplary “paradise” city. During these same years, the Boyar Duma was replaced by a Council of Ministers consisting of members of the Tsar’s inner circle; along with Moscow orders, new institutions were created in St. Petersburg. In 1708 the country was divided into provinces. In 1709, after the Battle of Poltava, a turning point in the war came and the tsar was able to pay more attention to internal political affairs.

Governance reform of Peter I

In 1711, setting off on the Prut campaign, Peter I founded the Governing Senate, which had the functions of the main body of executive, judicial and legislative power. In 1717, the creation of collegiums began - central bodies of sectoral management, founded in a fundamentally different way than the old Moscow orders. New authorities - executive, financial, judicial and control - were also created locally. In 1720, the General Regulations were published - detailed instructions for organizing the work of new institutions. In 1722, Peter signed the Table of Ranks, which determined the order of organization of military and civil service and was in effect until 1917. Even earlier, in 1714, a Decree on Single Inheritance was issued, which equalized the rights of owners of estates and estates. This was important for the formation of the Russian nobility as a single full-fledged class. But it is of paramount importance social sphere there was a tax reform that began in 1718. In Russia, a poll tax was introduced for males, for which regular population censuses (“audits of souls”) were carried out. During the reform, the social category of serfs was eliminated and the social status of some other categories of the population was clarified. In 1721, after the end of the Northern War, Russia was proclaimed an empire, and the Senate awarded Peter the titles “Great” and “Father of the Fatherland.”

When the sovereign obeys the law, then no one will dare to resist it.

Transformations in the economy

Peter I clearly understood the need to overcome the technical backwardness of Russia and in every possible way contributed to the development of Russian industry and trade, including foreign trade. Many merchants and industrialists enjoyed his patronage, among whom the Demidovs were the most famous. Many new plants and factories were built, and new industries emerged. However, its development in wartime conditions led to the priority development of heavy industry, which after the end of the war could no longer exist without state support. In fact, the enslaved position of the urban population, high taxes, the forced closure of the Arkhangelsk port and some other government measures were not conducive to the development of foreign trade. In general, the grueling war that lasted for 21 years, requiring large capital investments, obtained mainly through emergency taxes, led to the actual impoverishment of the country's population, mass escapes of peasants, and the ruin of merchants and industrialists.

Transformations of Peter I in the field of culture

The time of Peter I is a time of active penetration of elements of secular Europeanized culture into Russian life. Secular educational institutions began to appear, and the first Russian newspaper was founded. Peter made success in service for the nobles dependent on education. By a special decree of the tsar, assemblies were introduced, representing a new form of communication between people for Russia. Of particular importance was the construction of stone Petersburg, in which foreign architects took part and which was carried out according to the plan developed by the Tsar. They created a new urban environment with previously unfamiliar forms of life and pastime. The interior decoration of houses, the way of life, the composition of food, etc. changed. Gradually, a different system of values, worldview, and aesthetic ideas took shape in the educated environment. The Academy of Sciences was founded in 1724 (opened in 1725).

Personal life of the king

Upon returning from the Grand Embassy, Peter I finally broke up with his unloved first wife. Subsequently, he became friends with the captured Latvian Marta Skavronskaya (future Empress Catherine I), with whom he married in 1712.

There is a desire, there are a thousand ways; no desire - a thousand reasons!

On March 1, 1712, Peter I married Marta Samuilovna Skavronskaya, who converted to Orthodoxy and from that time was called Ekaterina Alekseevna.

Marta Skavronskaya's mother was a peasant and died early. Pastor Gluck took Martha Skavronskaya (that was her name then) into her upbringing. At first, Martha was married to a dragoon, but she did not become his wife, since the groom was urgently summoned to Riga. When the Russians arrived in Marienburg, she was taken as a prisoner. According to some sources, Marta was the daughter of a Livonian nobleman. According to others, she was a native of Sweden. The first statement is more reliable. When she was captured, B.P. took her in. Sheremetev, and A.D. took it from him or begged it. Menshikov, the latter - Peter I. Since 1703, she became a favorite. Three years before their church marriage, in 1709, Peter I and Catherine had a daughter, Elizabeth. Martha took the name Ekaterina after converting to Orthodoxy, although she was called by the same name (Katerina Trubacheva) when she was with A.D. Menshikov".

Marta Skavronskaya gave birth to several children to Peter I, of whom only daughters Anna and Elizaveta (the future Empress Elizaveta Petrovna) survived. Peter, apparently, was very attached to his second wife and in 1724 crowned her with the imperial crown, intending to bequeath the throne to her. However, shortly before his death, he learned about his wife’s infidelity with V. Mons. The relationship between the tsar and his son from his first marriage, Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich, did not work out either, who died under incompletely clarified circumstances in Peter and Paul Fortress in 1718 (for this purpose the Tsar created the Secret Chancellery). Peter I himself died from a disease of the urinary organs without leaving a will. The emperor had a whole bunch of illnesses, but uremia bothered him more than other ailments.

Results of Peter's reforms

Forgetting service for the sake of a woman is unforgivable. To be a prisoner of a mistress is worse than a prisoner in war; The enemy can have freedom more quickly, but the woman’s fetters are long-lasting.

The most important result of Peter's reforms was to overcome the crisis of traditionalism by modernizing the country. Russia became a full participant in international relations, pursuing an active foreign policy. Russia's authority in the world grew significantly, and Peter I himself became for many an example of a reformer sovereign. Under Peter, the foundations of Russian national culture were laid. The king also created a system of governance and administrative-territorial division of the country, which remained in place for a long time. At the same time, the main instrument of reform was violence. Petrine reforms not only did not rid the country of the previously established system of social relations embodied in serfdom, but, on the contrary, preserved and strengthened its institutions. This was the main contradiction of Peter’s reforms, the prerequisites for a future new crisis.

PETER I THE GREAT (article by P. N. Milyukov from the “Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron”, 1890 - 1907)

Peter I Alekseevich the Great- the first All-Russian Emperor, born on May 30, 1672, from the second marriage of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich with Natalya Kirillovna Naryshkina, a pupil of the boyar A.S. Matveev.

Contrary to the legendary stories of Krekshin, the education of young Peter proceeded rather slowly. Tradition forces a three-year-old child to report to his father, with the rank of colonel; in fact, he was not yet weaned at two and a half years old. We do not know when N. M. Zotov began teaching him to read and write, but it is known that in 1683 Peter had not yet finished learning the alphabet.

Don’t trust three: don’t trust a woman, don’t trust a Turk, don’t trust a non-drinker.

Until the end of his life, Peter continued to ignore grammar and spelling. As a child, he becomes acquainted with the “exercises of the soldier’s formation” and adopts the art of beating the drum; This is what limits his military knowledge to military exercises in the village. Vorobyov (1683). This fall, Peter is still playing wooden horses. All this did not go beyond the pattern of the usual “fun” of that time. royal family. Deviations begin only when political circumstances throw Peter off track. With the death of Tsar Fyodor Alekseevich, the silent struggle of the Miloslavskys and Naryshkins turns into an open clash. On April 27, the crowd gathered in front of the red porch of the Kremlin Palace shouted Peter as Tsar, beating his elder brother John; On May 15, on the same porch, Peter stood in front of another crowd, which threw Matveev and Dolgoruky onto the Streltsy spears. The legend depicts Peter as calm on this day of rebellion; it is more likely that the impression was strong and that this is where Peter’s well-known nervousness and hatred of the archers originated. A week after the start of the rebellion (May 23), the victors demanded from the government that both brothers be appointed kings; another week later (on the 29th), at the new request of the archers, due to the youth of the kings, the reign was handed over to Princess Sophia.

Peter's party was excluded from all participation in state affairs; Throughout Sophia’s regency, Natalya Kirillovna came to Moscow only for a few winter months, spending the rest of her time in the village of Preobrazhenskoye near Moscow. A significant number of noble families were grouped around the young court, not daring to throw in their lot with the provisional government of Sophia. Left to his own devices, Peter learned to endure any kind of constraint, to deny himself the fulfillment of any desire. Tsarina Natalya, a woman of “small intelligence,” according to the expression of her relative Prince. Kurakina, apparently cared exclusively about the physical side of raising her son.

From the very beginning we see Peter surrounded by “young guys, common people” and “young people of the first houses”; the former eventually gained the upper hand, and the “noble persons” were kept away. It is very likely that both simple and noble friends of Peter’s childhood games equally deserved the nickname “mischievous” given to them by Sophia. In 1683-1685, two regiments were organized from friends and volunteers, settled in the villages of Preobrazhenskoye and neighboring Semenovskoye. Little by little, Peter developed an interest in the technical side of military affairs, which forced him to look for new teachers and new knowledge. “For mathematics, fortification, turning and artifical lights” is under Peter a foreign teacher, Franz Timmermann. Peter's textbooks that have survived (from 1688?) testify to his persistent efforts to master the applied side of arithmetic, astronomical and artillery wisdom; the same notebooks show that the foundations of all this wisdom remained a mystery to Peter 1. But turning and pyrotechnics have always been Peter’s favorite pastimes.

The only major, and unsuccessful, intervention of the mother in the personal life of the young man was his marriage to E.F. Lopukhina, on January 27, 1689, before Peter turned 17 years old. This was, however, more a political than a pedagogical measure. Sophia also married Tsar John immediately upon reaching the age of 17; but he only had daughters. The very choice of a bride for Peter was the product of a party struggle: noble adherents of his mother offered a bride from the princely family, but the Naryshkins, with Tikh, won. Streshnev was at the head, and the daughter of a small nobleman was chosen. Following her, numerous relatives came to the court (“more than 30 people,” says Kurakin). Such a mass of new job seekers, who, moreover, did not know the “courtyard treatment,” caused general irritation against the Lopukhins at court; Queen Natalya soon “hated her daughter-in-law and wanted to see her and her husband in disagreement rather than in love” (Kurakin). This, as well as the dissimilarity of characters, explains that Peter’s “considerable love” for his wife “lasted only a year,” and then Peter began to prefer family life- marching, in the regimental hut of the Preobrazhensky Regiment.

A new occupation, shipbuilding, distracted him even further; From Yauza, Peter moved with his ships to Lake Pereyaslavl, and had fun there even in winter. Peter's participation in state affairs was limited, during Sophia's regency, to his presence at ceremonies. As Peter grew up and expanded his military amusements, Sophia began to become more and more worried about her power and began to take measures to preserve it. On the night of August 8, 1689, Peter was awakened in Preobrazhenskoye by archers who brought news of a real or imaginary danger from the Kremlin. Peter fled to Trinity; his followers ordered the convening of a noble militia, demanded commanders and deputies from the Moscow troops and inflicted short reprisals on Sophia’s main supporters. Sophia was settled in a monastery, John ruled only nominally; in fact, power passed to Peter's party. At first, however, “the royal majesty left his reign to his mother, and he himself spent his time in the amusements of military exercises.”

In honor of the New Year, make decorations from fir trees, amuse children, and ride down the mountains on sleds. But adults should not commit drunkenness and massacres - there are enough other days for that.

The reign of Queen Natalya seemed to contemporaries as an era of reaction against Sophia's reform aspirations. Peter took advantage of the change in his position only to expand his amusements to grandiose proportions. Thus, the maneuvers of the new regiments ended in 1694 with the Kozhukhov campaigns, in which “Tsar Fyodor Pleshbursky (Romodanovsky) defeated “Tsar Ivan Semenovsky” (Buturlin), leaving 24 real dead and 50 wounded on the amusing battlefield. The expansion of maritime fun prompted Peter to travel to the White Sea twice, and he was exposed to serious danger during his trip to the Solovetsky Islands. Over the years, the center of Peter's wild life becomes the house of his new favorite, Lefort, in the German settlement. “Then debauchery began, drunkenness was so great that it is impossible to describe that for three days, locked in that house, they were drunk and that many happened to die as a result” (Kurakin).

In Lefort’s house, Peter “began to make friends with foreign ladies, and Cupid began to be the first to be with one merchant’s daughter.” “From practice”, at Lefort’s balls, Peter “learned to dance in Polish”; the son of the Danish commissioner Butenant taught him fencing and horse riding, the Dutchman Vinius taught him the practice of the Dutch language; During a trip to Arkhangelsk, Peter changed into a Dutch sailor suit. In parallel with this assimilation of European appearance, there was a rapid destruction of the old court etiquette; ceremonial entrances to the cathedral church, public audiences and other “courtyard ceremonies” fell out of use. “Curses against noble persons” from the tsar’s favorites and court jesters, as well as the establishment of the “all-joking and all-drunk cathedral,” originate in the same era. In 1694, Peter's mother died. Although now Peter “he himself was forced to take over the administration, he did not want to bear the trouble and left the entire administration of his state to his ministers” (Kurakin). It was difficult for him to give up the freedom to which years of involuntary retirement had taught him; and subsequently he did not like to bind himself to official duties, entrusting them to other persons (for example, “Prince Caesar Romodanovsky, before whom Peter plays the role of a loyal subject), while he himself remained in the background. The government machine in the first years of Peter's own reign continues to move at its own pace; he interferes in this move only if and to the extent that it turns out to be necessary for his naval amusements.

Very soon, however, Peter’s “infantile play” with soldiers and ships leads to serious difficulties, to eliminate which it turns out to be necessary to significantly disturb the old state order. “We were joking near Kozhukhov, and now we are going to play near Azov” - this is what Peter reported to F.M. Apraksin at the beginning of 1695 about the Azov campaign. Already in the previous year, having become acquainted with the inconveniences White Sea, Peter began to think about transferring his maritime activities to some other sea. He fluctuated between the Baltic and the Caspian; the course of Russian diplomacy prompted him to prefer war with Turkey and Crimea, and the secret goal of the campaign was Azov - the first step towards access to the Black Sea.

The humorous tone soon disappears; Peter's letters become more laconic as the army and generals are revealed to be unprepared for serious actions. The failure of the first campaign forces Peter to make new efforts. The flotilla built in Voronezh, however, turns out to be of little use for military operations; the foreign engineers appointed by Peter are late; Azov surrenders in 1696 “by treaty, not by war.” Peter noisily celebrates the victory, but clearly feels the insignificance of success and the insufficient strength to continue the fight. He invites the boyars to grab “fortune by the hair” and find funds to build a fleet in order to continue the war with the “infidels” at sea.

The boyars entrusted the construction of ships to the “kumpanships” of secular and spiritual landowners who had at least 100 households; the rest of the population had to help with money. The ships built by the “companies” later turned out to be worthless, and this entire first fleet, which cost the population about 900 thousand rubles of that time, could not be used for any practical purposes. Simultaneously with the establishment of the “campanships” and in view of the same goal, i.e., war with Turkey, it was decided to equip an embassy abroad to consolidate the alliance against the “infidels.” “Bombardier” at the beginning of the Azov campaign and “captain” at the end, Peter now joins the embassy as “volunteer Peter Mikhailov”, with the aim of further studying shipbuilding.

I instruct the gentlemen senators to speak not according to what is written, but in your own words, so that the nonsense is visible to everyone.

On March 9, 1697, the embassy set out from Moscow, with the intention of visiting Vienna, the kings of England and Denmark, the pope, the Dutch states, the Elector of Brandenburg and Venice. Peter’s first impressions abroad were, as he put it, “not very pleasant”: the Riga commandant Dalberg took the tsar’s incognito too literally and did not allow him to inspect the fortifications: Peter later made a casus belli out of this incident. The magnificent meeting in Mitau and the friendly reception of the Elector of Brandenburg in Konigsberg improved matters. From Kolberg, Peter went forward, by sea, to Lubeck and Hamburg, trying to quickly reach his goal - a minor Dutch shipyard in Saardam, recommended to him by one of his Moscow acquaintances.

Here Peter stayed for 8 days, surprising the population of the small town with his extravagant behavior. The embassy arrived in Amsterdam in mid-August and remained there until mid-May 1698, although negotiations were completed already in November 1697. In January 1698, Peter went to England to expand his maritime knowledge and remained there for three and a half months, working mainly at the Deptford shipyard. The main goal of the embassy was not achieved, since the states resolutely refused to help Russia in the war with Turkey; for this, Peter used his time in Holland and England to acquire new knowledge, and the embassy was engaged in the purchase of weapons and all kinds of ship supplies; hiring sailors, artisans, etc.

Peter impressed European observers as an inquisitive savage, interested mainly in crafts, applied knowledge and all sorts of curiosities and not developed enough to be interested in the essential features of European political and cultural life. He is portrayed as an extremely hot-tempered and nervous person, quickly changing his mood and plans and unable to control himself in moments of anger, especially under the influence of wine.

The embassy's return route lay through Vienna. Peter experienced a new diplomatic setback here, since Europe was preparing for the War of the Spanish Succession and was busy trying to reconcile Austria with Turkey, and not about a war between them. Constrained in his habits by the strict etiquette of the Viennese court, finding no new attractions for curiosity, Peter hurried to leave Vienna for Venice, where he hoped to study the structure of galleys.

Speak briefly, ask for little, go away!

The news of the Streltsy revolt called him to Russia; On the way, he only managed to see the Polish King Augustus (in the town of Rava), and here; Among the three days of continuous fun, the first idea flashed to replace the failed plan for an alliance against the Turks with another plan, the subject of which, instead of the Black Sea that had slipped from the hands, would be the Baltic. First of all, it was necessary to put an end to the archers and the old order in general. Straight from the road, without seeing his family, Peter drove to Anna Mons, then to his Preobrazhensky yard. The next morning, August 26, 1698, he personally began cutting the beards of the first dignitaries of the state. The archers had already been defeated by Shein at the Resurrection Monastery and the instigators of the riot were punished. Peter resumed the investigation into the riot, trying to find traces of the influence of Princess Sophia on the archers. Having found evidence of mutual sympathy rather than specific plans and actions, Peter nevertheless forced Sophia and her sister Martha to cut their hair. He took advantage of this same moment to forcibly cut the hair of his wife, who was not accused of any involvement in the rebellion.

The king's brother, John, died back in 1696; no ties with the old no longer restrain Peter, and he indulges with his new favorites, among whom Menshikov comes first, in some kind of continuous bacchanalia, the picture of which Korb paints. Feasts and drinking bouts give way to executions, in which the king himself sometimes plays the role of executioner; from the end of September to the end of October 1698, more than a thousand archers were executed. In February 1699, hundreds of archers were executed again. The Moscow Streltsy army ceased to exist.

The decree of December 20, 1699 on a new calendar formally drew a line between the old and new times. On November 11, 1699, a secret agreement was concluded between Peter and Augustus, by which Peter pledged to enter Ingria and Karelia immediately after the conclusion of peace with Turkey, no later than April 1700; Livonia and Estland, according to Patkul's plan, were left to Augustus for himself. Peace with Turkey was concluded only in August. Peter used this period of time to create a new army, since “after the dissolution of the Streltsy, this state did not have any infantry.” On November 17, 1699, a recruitment of new 27 regiments was announced, divided into 3 divisions, headed by the commanders of the Preobrazhensky, Lefortovo and Butyrsky regiments. The first two divisions (Golovin and Weide) were fully formed by mid-June 1700; together with some other troops, up to 40 thousand in total, they were moved to the Swedish borders, the next day after the promulgation of peace with Turkey (August 19). To the displeasure of the allies, Peter sent his troops to Narva, taking which he could threaten Livonia and Estland. Only towards the end of September did the troops gather at Narva; It was only at the end of October that fire was opened on the city. During this time, Charles XII managed to put an end to Denmark and, unexpectedly for Peter, landed in Estland.

On the night of November 17–18, the Russians learned that Charles XII was approaching Narva. Peter left the camp, leaving command to Prince de Croix, unfamiliar with the soldiers and unknown to them - and the eight-thousand-strong army of Charles XII, tired and hungry, defeated Peter’s forty-thousand-strong army without any difficulty. The hopes aroused in Petra by the trip to Europe give way to disappointment. Charles XII does not consider it necessary to pursue such a weak enemy further and turns against Poland. Peter himself characterizes his impression with the words: “then captivity drove away laziness and forced him to hard work and art day and night.” Indeed, from this moment Peter is transformed. The need for activity remains the same, but it finds something else, best app; All Peter’s thoughts are now aimed at defeating his opponent and gaining a foothold in the Baltic Sea.

In eight years, he recruits about 200,000 soldiers and, despite the losses from the war and from military orders, increases the size of the army from 40 to 100 thousand. The cost of this army in 1709 cost him almost twice as much as in 1701: 1,810,000 r. instead of 982,000. For the first 6 years of the war, moreover, it was paid; subsidies to the Polish king are about one and a half million. If we add here the costs of the fleet, artillery, and the maintenance of diplomats, then the total expenditure caused by the war will be 2.3 million in 1701, 2.7 million in 1706 and 3.2 billion in 1710 Already the first of these figures was too large in comparison with the funds that were delivered to the state by the population before Peter (about 11/2 million).

A subordinate in front of his superiors should look dashing and stupid, so as not to embarrass his superiors with his understanding.

It was necessary to look for additional sources of income. At first, Peter cares little about this and simply takes from old ones for his own purposes. government agencies- not only their free balances, but even those amounts that were previously spent on another purpose; this disrupts the correct course of the state machine. And yet, large items of new expenses could not be covered by old funds, and Peter was forced to create a special state tax for each of them. The army was supported from the main income of the state - customs and tavern duties, the collection of which was transferred to a new central institution, the town hall. To maintain the new cavalry recruited in 1701, it was necessary to assign a new tax (“dragoon money”); exactly the same - for maintaining the fleet (“ship”). Then comes the tax on the maintenance of workers for the construction of St. Petersburg, “recruits”, “underwater”; and when all these taxes become familiar and merge into the total amount of permanent (“salary”), new emergency fees (“request”, “non-salary”) are added to them. And these direct taxes, however, soon turned out to be insufficient, especially since they were collected rather slowly and a significant part remained in arrears. Therefore, other sources of income were invented alongside them.

The earliest invention of this kind - stamp paper introduced on the advice of Alexei Alexandrovich Kurbatov - did not yield the profits expected from it. The damage to the coin was all the more important. Recoinage silver coin into a coin of lower denomination, but with the same nominal price, it gave 946 thousand in the first 3 years (1701-03), 313 thousand in the next three; from here foreign subsidies were paid. However, soon all the metal was converted into a new coin, and its value in circulation fell by half; Thus, the benefit from deteriorating the coin was temporary and was accompanied by enormous harm, lowering the value of all treasury receipts (along with a decline in the value of the coin).

A new measure to increase government revenues was the re-signing, in 1704, of old quitrent articles and the transfer of new quitrents; all owner-owned fisheries, home baths, mills, and inns were subject to quitrent, and the total figure of government revenues under this article rose by 1708 from 300 to 670 thousand annually. Further, the treasury took control of the sale of salt, which brought it up to 300 thousand in annual income, tobacco (this enterprise was unsuccessful) and a number of others raw foods, giving up to 100 thousand annually. All these private events satisfied the main goal - to somehow survive a difficult time.

During these years, Peter could not devote a single minute of attention to the systematic reform of state institutions, since the preparation of means of struggle took all his time and required his presence in all parts of the state. Peter began to come to the old capital only on Christmastide; here the usual riotous life was resumed, but at the same time the most urgent state affairs were discussed and resolved. The Poltava victory gave Peter the opportunity to breathe freely for the first time after the Narva defeat. The need to understand the mass of individual orders of the first years of the war; became more and more urgent; both the means of payment of the population and the treasury resources were greatly depleted, and a further increase in military spending was expected ahead. From this situation, Peter found the outcome that was already familiar to him: if there were not enough funds for everything, they had to be used for the most important thing, that is, for military affairs. Following this rule, Peter had previously simplified the financial management of the country, transferring taxes from individual localities directly into the hands of the generals for their expenses, and bypassing the central institutions where the money should have been received according to the old order.

It was most convenient to apply this method in the newly conquered country - Ingria, which was given to the “government” of Menshikov. The same method was extended to Kyiv and Smolensk - to put them in a defensive position against the invasion of Charles XII, to Kazan - to pacify unrest, to Voronezh and Azov - to build a fleet. Peter only summarizes these partial orders when he orders (December 18, 1707) “to paint the cities in parts, except for those that in the 100th century. from Moscow - to Kyiv, Smolensk, Azov, Kazan, Arkhangelsk." After the Poltava victory, this vague idea about the new administrative and financial structure of Russia received further development. The assignment of cities to central points, in order to collect any fees from them, presupposed a preliminary clarification of who should pay what in each city. To inform payers, a widespread census was appointed; to inform payments, it was ordered to collect information from previous financial institutions. The results of these preliminary works revealed that the state was experiencing a serious crisis. The census of 1710 showed that, as a result of continuous recruitment and escape from taxes, the paying population of the state greatly decreased: instead of 791 thousand households listed before the census of 1678, the new census counted only 637 thousand; in the entire north of Russia, which bore the main part of the financial burden to Peter, the decline even reached 40%.

In view of this unexpected fact, the government decided to ignore the figures of the new census, with the exception of places where they showed the income of the population (in the SE and in Siberia); in all other areas, it was decided to collect taxes in accordance with the old, fictitious figures of payers. And under this condition, however, it turned out that payments did not cover expenses: the first turned out to be 3 million 134 thousand, the last - 3 million 834 thousand rubles. About 200 thousand could be covered from salt income; the remaining half a million was a permanent deficit. During the Christmas congresses of Peter's generals in 1709 and 1710, the cities of Russia were finally distributed among 8 governors; everyone in his “province” collected all taxes and directed them, first of all, to the maintenance of the army, navy, artillery and diplomacy. These “four places” absorbed the entire stated income of the state; How the “provinces” would cover other expenses, and above all their own, local ones - this question remained open. The deficit was eliminated simply by cutting government spending by a corresponding amount. Since the maintenance of the army was the main goal when introducing “provinces,” the further step of this new structure was that each province was entrusted with the maintenance of certain regiments.

For constant relations with them, the provinces appointed their “commissars” to the regiments. The most significant drawback of this arrangement, introduced in 1712, was that it actually abolished the old central institutions, but did not replace them with any others. The provinces had direct contact with the army and with the highest military institutions; but there was no higher office above them that could control and approve their functioning. The need for such a central institution was felt already in 1711, when Peter I had to leave Russia for the Prut campaign. “For his absences” Peter created the Senate. The provinces had to appoint their own commissioners to the Senate, “to demand and adopt decrees.” But all this did not accurately determine the mutual relations of the Senate and the provinces. All attempts by the Senate to organize over the provinces the same control that the “Near Chancellery” established in 1701 had over orders; ended in complete failure. The irresponsibility of the governors was necessary consequence the fact that the government itself constantly violated the rules established in 1710-12. order of the provincial economy, took money from the governor for purposes other than those for which he was supposed to pay them according to the budget, freely disposed of the provincial cash sums and demanded from the governors more and more “devices”, i.e., an increase in income, at least at the cost oppression of the population.

The main reason for all these violations of the established order was that the budget of 1710 fixed the figures for the necessary expenses, but in reality they continued to grow and no longer fit within the budget. The growth of the army has now, however, slowed down somewhat; on the other hand, expenses quickly increased on the Baltic fleet, on buildings in the new capital (where the government finally moved its residence in 1714), and on the defense of the southern border. We had to again find new, extra-budgetary resources. It was almost useless to impose new direct taxes, since the old ones were paid worse and worse as the population became impoverished. Re-minting of coins and state monopolies also could not give more than what they had already given. In place of the provincial system, the question of restoring central institutions naturally arises; the chaos of old and new taxes, “salary”, “every year” and “request”, necessitates the consolidation of direct taxes; the unsuccessful collection of taxes based on fictitious figures for 1678 leads to the question of a new census and a change in the tax unit; Finally, the abuse of the system of state monopolies raises the question of the benefits of free trade and industry for the state.

The reform is entering its third and final phase: until 1710 it was reduced to the accumulation of random orders dictated by the need of the moment; in 1708-1712 Attempts were made to bring these orders into some purely external, mechanical connection; Now there is a conscious, systematic desire to erect a completely new state structure on theoretical foundations. The question to what extent Peter I himself personally participated in the reforms of the last period remains still controversial. An archival study of the history of Peter I has recently discovered a whole mass of “reports” and projects in which almost the entire content of Peter’s government activities was discussed. In these reports, presented by Russian and especially foreign advisers to Peter I, voluntarily or at the direct call of the government, the state of affairs in the state and the most important measures necessary to improve it were examined in great detail, although not always on the basis of sufficient familiarity with the conditions of Russian reality. Peter I himself read many of these projects and took from them everything that directly answered the questions that interested him at the moment - especially the question of increasing state revenues and developing Russia's natural resources. To solve more complex government problems, e.g. on trade policy, financial and administrative reform, Peter I did not have the necessary preparation; his participation here was limited to posing the question, mostly on the basis of verbal advice from someone around him, and developing the final wording of the law; all intermediate work - collecting materials, developing them and designing appropriate measures - was assigned to more knowledgeable persons. In particular, in relation to trade policy, Peter I himself “complained more than once that of all government affairs, nothing is more difficult for him than commerce and that he could never form a clear idea about this matter in all its connections” (Fokkerodt).

However, state necessity forced him to change the previous direction of Russian trade policy - and the advice of knowledgeable people played an important role in this. Already in 1711-1713. The government was presented with a number of projects that proved that the monopolization of trade and industry in the hands of the treasury ultimately harms the fiscal itself and that the only way to increase government revenues from trade is to restore freedom of commercial and industrial activity. Around 1715 the content of the projects became broader; foreigners take part in the discussion of issues, verbally and in writing instilling in the tsar and the government the ideas of European mercantilism - about the need for profitable things for the country trade balance and about the way to achieve it by systematic patronage of national industry and trade, by opening factories and factories, concluding commercial treaties and establishing trade consulates abroad.

Once he had grasped this point of view, Peter I, with his usual energy, carried it out in many separate orders. He creates a new trading port (St. Petersburg) and forcibly transfers trade there from the old one (Arkhangelsk), begins to build the first artificial waterways to connect St. Petersburg with central Russia, takes great care to expand active trade with the East (after his attempts in the West in this direction were not very successful), gives privileges to the organizers of new factories, imports craftsmen, the best tools, the best breeds of livestock, etc. from abroad.

Peter I was less attentive to the idea of financial reform. Although in this respect life itself shows the unsatisfactory nature of current practice, and a number of projects presented to the government discuss various possible reforms, nevertheless, he is only interested here in the question of how to distribute the maintenance of a new, standing army to the population. Already during the establishment of the provinces, expecting a quick peace after the Poltava victory, Peter I intended to distribute the regiments between the provinces, following the example of the Swedish system. This idea resurfaces in 1715; Peter I orders the Senate to calculate how much it will cost to maintain a soldier and an officer, leaving the Senate itself to decide whether this expense should be covered with the help of a house tax, as was the case before, or with the help of a capitation tax, as various “informers” advised.

The technical side of the future tax reform is being developed by Peter's government, and then he insists with all his energy on the speedy completion of the capitation census necessary for the reform and on the possible speedy implementation of the new tax. Indeed, the poll tax increases the figure of direct taxes from 1.8 to 4.6 million, accounting for more than half of the budget revenue (81/2 million). The question of administrative reform interests Peter I even less: here the very idea, its development, and its implementation belong to foreign advisers (especially Heinrich Fick), who suggested that Peter fill the lack of central institutions in Russia by introducing Swedish boards. To the question of what primarily interested Peter in his reformation activities, Vokerodt already gave an answer very close to the truth: “he especially and with all zeal tried to improve his military forces.”

Indeed, in his letter to his son, Peter I emphasizes the idea that through military work “we went from darkness to light, and (we), who were not known in the world, are now revered.” “The wars that occupied Peter I all his life (continues Fockerodt), and the treaties concluded with foreign powers regarding these wars forced him to also pay attention to foreign affairs, although he relied here mostly on his ministers and favorites... His very favorite and a pleasant occupation was shipbuilding and other matters related to navigation. It entertained him every day, and even the most important state affairs had to be ceded to him... Peter I cared little or not at all about internal improvements in the state - legal proceedings, economy, income and trade - in the first thirty years of his reign, and was satisfied , if only his admiralty and army were sufficiently supplied with money, firewood, recruits, sailors, provisions and ammunition.”

Immediately after the Poltava victory, Russia's prestige abroad rose. From Poltava, Peter I goes straight to meetings with the Polish and Prussian kings; in mid-December 1709 he returned to Moscow, but in mid-February 1710 he left it again. He spends half the summer before the capture of Vyborg on the seaside, the rest of the year in St. Petersburg, dealing with its construction and the marriage alliances of his niece Anna Ioannovna with the Duke of Courland and his son Alexei with Princess Wolfenbüttel.

On January 17, 1711, Peter I left St. Petersburg on the Prut campaign, then went straight to Carlsbad, for treatment with water, and to Torgau, to attend the marriage of Tsarevich Alexei. He returned to St. Petersburg only in the New Year. In June 1712, Peter again left St. Petersburg for almost a year; he goes to the Russian troops in Pomerania, in October he is treated in Karlsbad and Teplitz, in November, having visited Dresden and Berlin, he returns to the troops in Mecklenburg, at the beginning of the next 1713 he visits Hamburg and Rendsburg, passes through Hanover and Wolfenbüttel in February Berlin, for a meeting with the new king Frederick William, then returns to St. Petersburg.

A month later he was already on a Finnish voyage and, returning in mid-August, continued to undertake sea trips until the end of November. In mid-January 1714, Peter I left for Revel and Riga for a month; On May 9, he again goes to the fleet, wins a victory with it at Gangeuda and returns to St. Petersburg on September 9. In 1715, from the beginning of July to the end of August, Peter I was with his fleet on the Baltic Sea. At the beginning of 1716, he left Russia for almost two years; On January 24, he leaves for Danzig, for the wedding of Ekaterina Ivanovna’s niece with the Duke of Mecklenburg; from there, through Stettin, he goes to Pyrmont for treatment; in June he goes to Rostock to join the galley squadron, with which he appears near Copenhagen in July; in October, Peter I goes to Mecklenburg; from there to Havelsberg, for a meeting with the Prussian king, in November - to Hamburg, in December - to Amsterdam, at the end of March of the following 1717 - to France. In June we see him in Spa, on the waters, in the middle of the field - in Amsterdam, in September - in Berlin and Danzig; On October 10 he returns to St. Petersburg.

For the next two months, Peter I led a fairly regular life, devoting his mornings to work at the Admiralty and then driving around the St. Petersburg buildings. On December 15, he goes to Moscow, waits there for his son Alexei to be brought from abroad, and on March 18, 1718, leaves back to St. Petersburg. On June 30, Alexei Petrovich was buried in the presence of Peter; in early July, Peter I left for the fleet and, after a demonstration near the Åland Islands, where peace negotiations were being held, he returned to St. Petersburg on September 3, after which he went to the seaside three more times and once to Shlisselburg.

The following year, 1719, Peter I left on January 19 for the Olonets waters, from where he returned on March 3. On May 1 he went to sea, and returned to St. Petersburg only on August 30. In 1720, Peter I spent the month of March in the Olonets waters and factories: from July 20 to August 4, he sailed to the Finnish shores. In 1721 he traveled by sea to Riga and Revel (March 11 - June 19). In September and October, Peter celebrated the Peace of Nystad in St. Petersburg, and in December in Moscow. In 1722, on May 15, he left Moscow for Nizhny Novgorod, Kazan and Astrakhan; On July 18, he set off from Astrakhan on a Persian campaign (to Derbent), from which he returned to Moscow only on December 11. Having returned to St. Petersburg on March 3, 1723, Peter I already left for the new Finnish border on March 30; in May and June he was engaged in equipping the fleet and then went to Revel and Rogerwick for a month, where he built a new harbor.

In 1724, Peter I suffered greatly from ill health, but it did not force him to abandon the habits of a nomadic life, which accelerated his death. In February he goes to the Olonets waters for the third time; at the end of March he goes to Moscow for the coronation of the Empress, from there he makes a trip to Millerovo Vody and on June 16 leaves for St. Petersburg; in the fall he travels to Shlisselburg, to the Ladoga Canal and the Olonets factories, then to Novgorod and Staraya Rusa to inspect the salt factories: only when the autumn weather decisively prevents sailing along the Ilmen, Peter I returns (October 27) to St. Petersburg. On October 28, he goes from lunch with Pavel Ivanovich Yaguzhinsky to a fire that happened on Vasilyevsky Island; On the 29th he goes by water to Sesterbek and, having met a boat that has run aground on the road, he helps remove its soldiers from waist-deep water. Fever and fever prevent him from traveling further; he spends the night in place and returns to St. Petersburg on November 2. On the 5th he invites himself to the wedding of a German baker, on the 16th he executes Mons, on the 24th he celebrates the betrothal of his daughter Anna to the Duke of Holstein. Celebrations resume on the occasion of the choice of a new prince-pope, January 3rd and 4th, 1725.

Busy life goes on as usual until the end of January, when, finally, it is necessary to resort to doctors, whom Peter I had not wanted to listen to until that time. But time is lost and the disease is incurable; On January 22, an altar is erected near the patient’s room and he is given communion, on the 26th, “for the sake of his health,” he is released from the convicts’ prison, and on January 28, at a quarter past six in the morning, Peter I dies without having time to decide the fate of the state.

A simple list of all the movements of Peter I over the last 15 years of his life gives one a sense of how Peter’s time and attention were distributed between various types of activities. After the navy, army and foreign policy, Peter I devoted the greatest part of his energy and his concerns to St. Petersburg. St. Petersburg is Peter’s personal business, carried out by him despite the obstacles of nature and the resistance of those around him. Tens of thousands of Russian workers fought with nature and died in this struggle, summoned to the deserted outskirts populated by foreigners; Peter I himself dealt with the resistance of those around him, with orders and threats.

The judgments of Peter I’s contemporaries about this undertaking can be read from Fokerodt. Opinions about the reform of Peter I differed extremely during his lifetime. A small group of close collaborators held an opinion, which Mikhail Lomonosov later formulated with the words: “he is your God, your God was, Russia.” The masses, on the contrary, were ready to agree with the schismatics’ assertion that Peter I was the Antichrist. Both proceeded from the general idea that Peter carried out a radical revolution and created new Russia, not similar to the previous one. A new army, a navy, relations with Europe, and finally, a European appearance and European technology - all these were facts that caught the eye; Everyone recognized them, differing only fundamentally in their assessment.

What some considered useful, others considered harmful to Russian interests; what some considered a great service to the fatherland, others saw as a betrayal of their native traditions; finally, where some saw a necessary step forward on the path of progress, others recognized a simple deviation caused by the whim of a despot.

Both views could provide factual evidence in their favor, since in the reform of Peter I both elements were mixed - both necessity and chance. The element of chance came out more while the study of the history of Peter was limited outside reform and personal activities of the transformer. The history of the reform, written according to his decrees, should have seemed exclusively Peter’s personal matter. Other results should have been obtained by studying the same reform in connection with its precedents, as well as in connection with the conditions of contemporary reality. A study of the precedents of Peter's reform showed that in all areas of public and state life- in the development of institutions and classes, in the development of education, in the environment of private life - long before Peter I, the very tendencies that were brought to triumph by Peter's reform were revealed. Being thus prepared by the entire past development of Russia and constituting the logical result of this development, the reform of Peter I, on the other hand, even under him does not yet find sufficient ground in Russian reality, and therefore even after Peter in many ways remains formal and visible for a long time.

New dress and “assemblies” do not lead to the adoption of European social habits and decency; in the same way, the new institutions borrowed from Sweden are not based on the corresponding economic and legal development of the masses. Russia is among the European powers, but for the first time only to become an instrument in the hands of European politics for almost half a century. Of the 42 digital provincial schools opened in 1716-22, only 8 survive until the middle of the century; out of 2000 students recruited, mostly by force, by 1727 only 300 in all of Russia actually graduated. Higher education, despite the Academy project, and lower education, despite all the orders of Peter I, remain a dream for a long time.

According to the decrees of January 20 and February 28, 1714, children of nobles and clerks, clerks and clerks, must learn numbers, i.e. arithmetic, and some part of geometry, and was subject to “a fine such that he will not be free to marry until he learns this”; crown certificates were not given without a written certificate of training from the teacher. For this purpose, it was prescribed that schools should be established in all provinces at the bishop's houses and in noble monasteries, and that teachers would send there students from the mathematical schools established in Moscow around 1703, which were then real gymnasiums; The teacher was given a salary of 300 rubles a year using our money.

The decrees of 1714 introduced completely new fact into the history of Russian education, compulsory education of the laity. The business was conceived on an extremely modest scale. For each province, only two teachers were appointed from students of mathematics schools who had learned geography and geometry. Numerals, elementary geometry and some information on the law of God, contained in the primers of that time - this is the entire composition of elementary education, recognized as sufficient for the purposes of the service; its expansion would be to the detriment of the service. Children had to go through the prescribed program between the ages of 10 and 15, when school necessarily ended because service began.

Students were recruited from everywhere, like hunters into the then regiments, just to staff the institution. 23 students were recruited to the Moscow engineering school. Peter I demanded that the set be increased to 100 and even 150 people, only on the condition that two thirds be from noble children. The educational authorities were unable to comply with the instructions; a new angry decree - to recruit the missing 77 students from all ranks of people, and from the children of the courtiers, from the capital's nobility, behind whom there are at least 50 peasant households - forcibly.

This character of the then school in the composition and program of the Maritime Academy is even more clear. In this planned predominantly noble and specially technical institution, out of 252 students, only 172 were from the nobility, the rest were commoners. IN upper classes large astronomy, flat and round navigation were taught, and in the lower classes 25 commoners learned the alphabet, 2 books of hours from the nobility and 25 commoners, 1 psalter from the nobility and 10 commoners, and letters from 8 commoners.

Schooling was fraught with many difficulties. It was already difficult to teach and study even then, although the school was not yet constrained by regulations and supervision, and the tsar, busy with war, cared about the school with all his soul. There was a shortage of necessary teaching aids, or they were very expensive. The state printing house, the Printing House in Moscow, which published textbooks, in 1711 bought from its own reference book, proofreader, hierodeacon Herman, the Italian lexicon needed “for school work” for 17 ½ rubles with our money. In 1714, the engineering school demanded 30 geometries and 83 books of sines from the Printing House. The printing house sold the geometry for 8 rubles a copy with our money, but wrote about the sines that it didn’t have them at all.

The school, which turned the education of youth into the training of animals, could only push away from itself and helped to develop among its pupils a unique form of counteraction - escape, a primitive, not yet improved way of students fighting their school. School runaways, together with recruits, have become a chronic ailment of Russian public education and Russian state defense. This school desertion, the then form of an educational strike, will become a completely understandable phenomenon for us, without ceasing to be sad, if we take into account the difficultly imaginable language in which foreign teachers were taught, clumsy and, moreover, difficult to obtain textbooks, and the methods of the then pedagogy, which did not at all want to to please students, let us add the government’s view of schooling not as a moral need of society, but as a natural service for young people, preparing them for compulsory service. When school was viewed as the threshold of a barracks or office, then young people learned to look at school as a prison or hard labor, from which it is always pleasant to escape.

In 1722, the Senate published the highest decree for public information... This decree of His Majesty the Emperor and Autocrat of All Russia announced publicly that 127 schoolchildren fled from the Moscow navigation school, which depended on the St. Petersburg Maritime Academy, which resulted in the loss of the academic sum of money, because These schoolchildren are scholarship holders, “living for many years and taking their salary, they fled.” The decree delicately invited fugitives to report to school at the specified time under the threat of a fine for the children of the gentry and a more sensitive “punishment” for the lower ranks. Attached to the decree was a list of fugitives, as persons worthy of the attention of the entire empire, which was informed that 33 students had fled from the nobility, and among them Prince A. Vyazemsky; the rest were children of reiters, guards soldiers, commoners, up to 12 people from boyar serfs; The composition of the school at that time was so diverse.

Things went badly: children were not sent to new schools; they were recruited by force, kept in prisons and behind guards; at 6 years old there are few places where these schools are located; the townspeople asked the Senate to keep their children away from digital science, so as not to distract them from their father’s affairs; of the 47 teachers sent to the province, eighteen did not find students and returned back; The Ryazan school, opened only in 1722, enrolled 96 students, but 59 of them fled. Vyatka governor Chaadaev, who wanted to open a digital school in his province, met opposition from the diocesan authorities and the clergy. To recruit students, he sent soldiers from the voivodeship office around the district, who grabbed everyone fit for school and took them to Vyatka. The matter, however, failed.

Peter I died February 8 (January 28, old style) 1725, in St. Petersburg.

On January 13, 1991, the Day was established Russian press. The date is associated with the birthday of the first Russian newspaper founded by Peter I.

Date of publication or update 12/15/2017

Peter I Alekseevich the Great

Years of life: 1672-1725

Reign: 1689-1725

Russian Tsar (1682). The first Russian emperor (since 1721), an outstanding statesman, diplomat and commander, all his activities were related to reforms.

From the Romanov dynasty.

In the 1680s. under the leadership of the Dutchman F. Timmerman and the Russian master R. Kartsev Peter I studied shipbuilding, and in 1684 he sailed on his boat along the Yauza River, and later along Lake Pereyaslavl, where he founded the first shipyard for the construction of ships.

On January 27, 1689, Peter, by order of his mother, married Evdokia Lopukhina, the daughter of a Moscow boyar. But the newlyweds spent time with friends in the German settlement. There, in 1691, he met the daughter of a German artisan, Anna Mons, who became his lover. But according to Russian custom, having married, he was considered an adult and could lay claim to independent rule.

But Princess Sophia did not want to lose power and organized a revolt of the archers against Peter. Having learned about this, Peter hid in the Trinity-Sergius Lavra. Remembering how the archers killed many of his relatives, he experienced real horror. From that time on, Peter developed nervous tics and convulsions.

Peter I, Emperor of All Russia. Engraving from the early 19th century.

But soon Petr Alekseevich came to his senses and brutally suppressed the uprising. In September 1689, Princess Sophia was exiled to the Novodevichy Convent, and her supporters were executed. In 1689, having removed his sister from power, Pyotr Alekseevich became the de facto king. After the death of his mother in 1695, and in 1696 of his brother-co-ruler Ivan V, on January 29, 1696, he became an autocrat, the sole king of all Rus' and legally.

Peter I, Emperor of All Russia. Portrait. Unknown artist of the late 18th century.

Having barely established himself on the throne, Peter I personally participated in the Azov campaigns against Turkey (1695–1696), which ended with the capture of Azov and access to the shores of the Sea of Azov. Thus, Russia's first access to the southern seas was opened.

Under the guise of studying maritime affairs and shipbuilding, Peter volunteered at the Great Embassy in 1697–1698. to Europe. There, under the name of Peter Mikhailov, the tsar completed a full course of artillery sciences in Brandenburg and Koenigsberg, worked as a carpenter in the shipyards of Amsterdam, studied naval architecture and plan drawing, and completed a theoretical course in shipbuilding in England. On his orders, instruments, weapons, and books were purchased in England, and foreign craftsmen and scientists were invited. The British said about Peter that there was no craft that the Russian Tsar would not have become familiar with.

Portrait Peter I. Artist A. Antropov. 1767

At the same time, the Grand Embassy prepared the creation of the Northern Alliance against Sweden, which finally took shape only 2 years later (1699). Summer 1697 Peter I held negotiations with the Austrian emperor, but having received news of the impending uprising of the Streltsy, which was organized by Princess Sophia, who promised many privileges in the event of the overthrow of Peter, he returned to Russia. On August 26, 1698, the investigation into the Streltsy case did not spare any of the rebels (1,182 people were executed, Sophia and her sister Martha were tonsured as nuns).

Returning to Russia, Peter I began his transformative activities.

In February 1699, on his orders, the unreliable rifle regiments were disbanded and the formation of regular soldiers and dragoons began. Soon, decrees were signed, under pain of fines and flogging, ordering men to “cut their beards,” wear European-style clothing, and women to uncover their hair. Since 1700, a new calendar was introduced with the beginning of the year on January 1 (instead of September 1) and chronology from the “Nativity of Christ”. All these actions Peter I provided for the breaking of ancient mores.

At the same time Peter I began serious changes in government. country. Over the course of more than 35 years of rule, he managed to carry out many reforms in the field of culture and education. Thus, the monopoly of the clergy on education was eliminated, and secular schools were opened. Under Peter, the School of Mathematical and Navigational Sciences (1701), the Medical-Surgical School (1707) - the future Military Medical Academy, the Naval Academy (1715), the Engineering and Artillery Schools (1719), and translator schools were opened. at the collegiums. In 1719, the first museum in Russian history began to operate - the Kunstkamera with a public library.

Monument to Peter the Great at the House of Peter the Great in St. Petersburg.

Primers were published educational cards, the beginning of a systematic study of the country's geography and mapping was laid. The spread of literacy was facilitated by the reform of the alphabet (cursive was replaced by civil script, 1708), and the publication of the first Russian printed newspaper Vedomosti (from 1703). In the era Peter I many buildings for state and cultural institutions, the architectural ensemble of Peterhof (Petrodvorets) were erected.

However, reform activities Peter I took place in a bitter struggle with the conservative opposition. The reforms provoked resistance from the boyars and clergy (conspiracy of I. Tsikler, 1697).

In 1700 Peter I concluded the Peace of Constantinople with Turkey and began a war with Sweden in alliance with Poland and Denmark. Peter's opponent was the 18-year-old Swedish king Charles XII. In November 1700 they first encountered Peter near Narva. The troops of Charles XII won this battle, since Russia did not yet have a strong army. But Peter learned a lesson from this defeat and actively began strengthening the Russian armed forces. Already in 1702, all the lands along the Niva to the Gulf of Finland were cleared of Swedish troops.

Monument to Peter the Great in the Peter and Paul Fortress.

However, the war with Sweden, called the Northern War, still continued. On June 27, 1709, near the Poltava fortress, the great Battle of Poltava took place, which ended in the complete defeat of the Swedish army. Peter I He himself led his troops and participated in the battle along with everyone else. He encouraged and inspired the soldiers, saying his famous words: “You are fighting not for Peter, but for the state entrusted to Peter. And about Peter, know that life is not dear to him, if only Russia lives, its glory, honor and prosperity!” Historians write that on the same day, Tsar Peter threw a big feast, invited the captured Swedish generals to it and, returning their swords to them, said: “... I drink to the health of you, my teachers in the art of war.” After the Battle of Poltava, Peter forever secured access to the Baltic Sea. From now on foreign countries were forced to reckon with the strong power Russia.

Tsar Peter I did a lot for Russia. Under him, industry actively developed and trade expanded. New cities began to be built throughout Russia, and the streets in the old ones were illuminated. With the emergence of the all-Russian market, the economic potential of the central government increased. And the reunification of Ukraine and Russia and the development of Siberia turned Russia into the greatest state in the world.

During Peter the Great's time, exploration of ore wealth was actively carried out, iron foundries and weapons factories were built in the Urals and Central Russia, canals and new strategic roads were laid, shipyards were built, and with them new cities arose.

However, the weight of the Northern War and reforms fell heavily on the peasantry, who made up the majority of the Russian population. Discontent erupted in popular uprisings (Astrakhan uprising, 1705; Peasant War led by K.A. Bulavin, 1707–1708; unrest of the Bashkirs 1705–1711), which were suppressed by Peter with cruelty and indifference.

After the suppression of the Bulavinsky revolt Peter I carried out the regional reform of 1708–1710, which divided the country into 8 provinces headed by governors and governors general. In 1719, the provinces were divided into provinces, and the provinces into counties.

The Decree on Single Inheritance of 1714 equalized estates and patrimonial estates and introduced primogeniture (granting the right to inherit real estate to the eldest of the sons), the purpose of which was to ensure the stable growth of noble land ownership.

Household affairs not only did not occupy Tsar Peter, but rather depressed him. His son Alexei showed disagreement with his father's vision of proper government. After his father's threats, Alexey fled to Europe in 1716. Peter, declaring his son a traitor, imprisoned him in a fortress and in 1718 personally sentenced him to death. death penalty Alexey. After these events, suspicion, unpredictability and cruelty settled into the king’s character.

Strengthening its position in the Baltic Sea, Peter I back in 1703, he founded the city of St. Petersburg at the mouth of the Neva River, which turned into a sea trading port designed to serve the needs of all of Russia. By founding this city, Peter “cut a window to Europe.”

In 1720 he wrote the Naval Charter and completed the reform of city government. The Chief Magistrate in the capital (as a collegium) and magistrates in the cities were created.

In 1721, Peter finally concluded the Treaty of Nystad, ending the Northern War. According to the Peace of Nystad, Russia regained the Novgorod lands near Ladoga that had been torn away from it and acquired Vyborg in Finland and the entire Baltic region with Ravel and Riga. For this victory, Peter I received the title of “Father of the Fatherland, Emperor of All Russia, Peter the Great"Thus, the long process of formation of the Russian Empire was formally completed.

In 1722, a Table of Ranks of all military, civil and court service ranks was published, according to which family nobility could be obtained “for blameless service to the emperor and the state.”

Peter's Persian campaign in 1722–1723 secured the western coast of the Caspian Sea with the cities of Derbent and Baku for Russia. There at Peter I For the first time in Russian history, permanent diplomatic missions and consulates were established.

In 1724, a decree was issued on the opening of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences with a gymnasium and a university.